On 25 October 2020, Ukraine will hold the country’s first nationwide local elections since completion of the initial phase of far-reaching decentralization reforms launched in April 2014. This gives the vote added significance as an important step forward for representative democracy in Ukraine and the adoption of European standards in self-governance.

For obvious reasons, local elections cannot take place in the Russian-occupied parts of eastern Ukraine. Moscow continues to call for a vote in the Kremlin-controlled areas of the Donbas region prior to de-occupation, but Kyiv has sensibly ruled out any elections until Ukrainian control is reestablished.

While few would argue with the Ukrainian logic of rejecting the idea of any vote staged in areas beyond government control, there is currently a debate within Ukraine regarding local elections in government-controlled areas of Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts in the immediate vicinity of the so-called contact line separating Ukrainian and Russian-led forces. The Central Electoral Commission has decided not to conduct elections in 18 such communities.

Since 2015, most frontline areas in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts have not been self-governed. Instead, they have been subject to temporary Military-Civil Administrations (MCAs). The key staff of MCAs are directly appointed by Kyiv and subordinated to the Commander of Ukraine’s Joint Forces Operation (JFO) in the Donbas.

Ukraine’s February 2015 law “On Military-Civilian Administrations” was initially supposed to expire after one year, but it has since been repeatedly prolonged and amended. Meanwhile, the number of municipal and sub-regional MCAs at the local and rayon levels has gradually increased.

MCAs hold all ordinary legislative and executive powers as well some emergency powers in the areas where they operate. This form of military-civil administration is a temporary solution to the problem of local government in areas that remain active or potential combat zones as well as Russian targets. In conditions of war-related political instability and economic deprivation, the MCAs are meant to secure elementary order and prevent Russian subversion across the contact line.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

While arguably a security necessity, the MCAs are in obvious contradiction to the democratic logic of Ukraine’s far-reaching decentralization reforms since 2014. As Konstantin Reutski and Ioulia Shukan noted in one of the first papers on this topic with the telling title The Temptation of Autocracy: Military-Civil Administrations in the Government-Controlled Territories in the Vicinity of the Contact Line: “In the absence of an elected representative body, collective decision-making and separation of legislative and executive functions, checks and balances are weak. The MCA heads exercise personal control over their administrations: they hire and fire MCA employees, oversee the entire operation and are personally responsible for all areas of the MCA’s performance. In addition to this, they are the sole managers of the MCA’s budget. The law on military-civil administrations does not require any community boards to be established in association with the MCAs, and this lack of external supervision further increases the personal power vested in the MCA head and removes all barriers to autocratic governance.”

This arrangement was never supposed to be permanent. If Ukraine had made more progress towards peace, the coming local elections would have represented a good opportunity to transit away from the MCAs toward elected local authorities. Sadly, that is not the case.

It would currently be premature to hold elections in most MCA-ruled areas for a number of reasons. Technical problems include the absence of many residents due to the military threat, along with the destruction of much of the physical and social infrastructure necessary to conduct meaningful electoral campaigns. Typically, MCA-governed territories are especially vulnerable to Russian infiltration and disinformation efforts, with Kremlin media still enjoying a high degree of reach along the contact line.

Perhaps most importantly, the nature of present conditions of these areas means that local deputies elected in October would find themselves with little to decide. Most of the everyday functions performed by their colleagues elsewhere in Ukraine are simply not relevant to front line communities, where normal economic and social activities remain extremely limited. Instead, the priorities of the local administrations along the 400km front line concern security and defense along with basics such as stable provision of electricity, water, and heat together with the repair of critical infrastructure.

Rather than conducting local elections in front line communities, Ukraine will have to maintain the MCA system for as long as necessary. At the same time, it may make sense to introduce new legislation that would improve the functionality of these administrations. A modified MCA law could provide for greater engagement of civil society as well as better feedback mechanisms between administration staff and local communities.

In many cases, the MCA heads are already in close contact not only with state-run institutions like schools and hospitals, but also with local NGOs, businesses, political activists, and the media. These relationships could benefit from some form of legal regulation and the creation of official advisory councils attached to the MCAs.

Eurasia Center events

Additionally, local communities could be included in the process of choosing appropriate candidates for the staffing of MCAs. It may also be useful to set up a formalized complaints procedure allowing local civic organizations, business associations, media outlets, and political parties to officially report misconduct by MCA representatives to the JFO headquarters.

Such measures would still not bring the current MCA system into line with the democratic principles of decentralized local self-government that operate elsewhere in Ukraine. However, it would place the initially temporary MCAs on a more sustainable political basis. With little sign of a definitive end to the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War, the MCAs may have to be retained for years to come.

Moreover, in the future, this model of extraordinary local governance consisting of centrally appointed MCA staff and community councils may provide a template for provisional administration of the territories currently under Russian occupation. After their liberation, the demilitarization and reintegration of these areas will likely be a matter of several stages. In that context, the MCAs can serve as a temporary institutional solution for a transitional phase before the currently occupied territories are fully included into Ukraine’s system of decentralized local self-government.

Andreas Umland is General Editor of the book series “Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society” published by ibidem Press in Stuttgart, and Senior Expert at the Ukrainian Institute for the Future in Kyiv. In July 2020, he took part in the eighth International Monitoring Mission to the Donbas contact line conducted by the Ukrainian Charity Fund “Vostok SOS” and German NGO “Deutsch-Russischer Austausch,” with the support of the German Foreign Office within the framework of the “Dialogue for Understanding and Law: Civil Society-led Conflict Solution in the Donbas” project.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values, and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia, and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

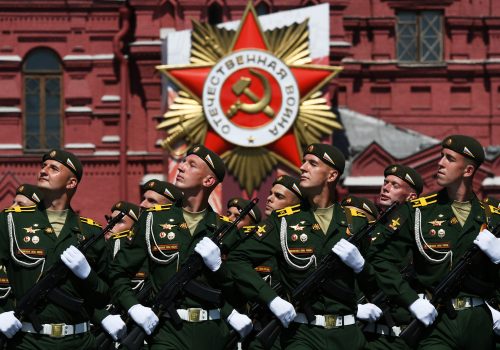

Image: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy pictured during an August 2020 visit to the front line in eastern Ukraine. The ongoing conflict with Russia makes it impossible for areas close to the front line to participate in Ukraine's October 2020 local elections. REUTERS/Gleb Garanich