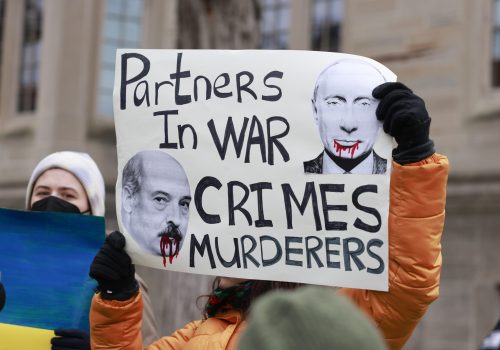

Vladimir Putin’s only international ally Alyaksandr Lukashenka is actively seeking to distance himself from Russia’s faltering invasion of Ukraine and sees the conflict as an opportunity to rebuild ties with the West, says Ukrainian Presidential Advisor Oleksiy Arestovych.

In an April 24 interview with Meduza, Arestovych claimed the Belarus dictator is currently conducting secret negotiations with the West while protesting his innocence over his country’s status as a partner and accomplice in Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. According to Arestovych, Lukashenka’s key message is “It’s not my fault. He [Putin] came to me.”

Reports of ongoing talks between Lukashenka and Western officials are the latest indication that the Belarus ruler is no longer comfortable playing a junior role in Putin’s war. Instead, he is trying to exploit the conflict in order to rehabilitate himself and bring an end to an extended period of international isolation dating back to the rigged Belarusian presidential election of August 2020.

Lukashenka’s heavy-handed response to Belarusian protests over the disputed election made him a global pariah and left him increasingly dependent on the Kremlin for his political survival. This brought the curtain down on a longstanding geopolitical balancing act that had seen the Belarus strongman skillfully plot a course between Russia and the West. Since August 2020, Lukashenka has found himself obliged to grant Moscow far greater political and economic influence in Belarus while also permitting the unofficial merger of the Belarusian and Russian militaries.

Putin’s February invasion of Ukraine was partially launched from Belarus, with Russian troops advancing on Kyiv from bases just across the Belarusian border. Lukashenka also allowed Russia to use his country as a platform for air raids and missile strikes against Ukrainian targets, effectively turning Belarus into an active participant in the conflict.

Despite Lukashenka’s reliance on Russia, Putin has not been entirely successful in his efforts to involve Belarus more directly in the war. Crucially, Lukashenka has withstood considerable Kremlin pressure and refused to send his troops into Ukraine.

This reluctance reflects widespread anti-war sentiment in Belarus along with alarm among serving Belarusian officers over the scale of the military setbacks suffered by Putin’s army during the opening weeks of the conflict. Public opposition to Belarus’s supporting role in the war has led to activism including efforts to sabotage the country’s rail networks and prevent Russian military personnel and equipment from reaching Ukraine.

From the very start of the invasion, Lukashenka has publicly denied participating directly in the war and has sought to present himself as a possible mediator. He hosted the first three rounds of talks between Russian and Ukrainian officials on Belarusian territory, leading to personal thanks from Putin for making the negotiations possible. Lukashenka also spoke directly with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy prior to the first meeting of Russian and Ukrainian delegations in Belarus.

Zelenskyy is not the only international leader who has called Lukashenka since the outbreak of hostilities. The Belarus dictator has also spoken with French President Emmanuel Macron, the first such contact since the beginning of the Belarusian political crisis in August 2020. Regime officials in Minsk reported that Macron and Lukashenka discussed “the future of Europe and Belarus’s place in this world order.”

Eurasia Center events

Belarusian diplomats are now actively seeking to use the war in Ukraine to re-establish the legitimacy of the Lukashenka regime. On April 6, Belarusian Foreign Minister Uladzimir Makei appealed directly to the EU for a renewal of dialogue. “In the current situation, we all need to abandon accusations and labeling, inflammatory rhetoric, and unilateral restrictive measures and rethink the paradigm that will determine the future of Belarus–EU relations and that of European security for the years ahead,” he wrote.

Despite Lukashenka’s aggressive rhetoric toward the EU, he has also recently implemented a number of measures that seem designed to improve relations with Brussels. The Minsk strongman has relaxed the detention measures of some political prisoners and allowed their release from prison to house arrest. The Belarusian authorities have also announced a visa-free regime for citizens of Latvia and Lithuania.

Franak Viachorka, who serves as an advisor to exiled Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, has cautioned against any Western efforts to bring Lukashenka in from the cold. Viachorka argues that it is naïve to believe the Belarus dictator can realistically end his reliance on Russia. He also warns that the Lukashenka regime is cynically seeking to exploit Western concerns over the war in Ukraine.

Western attempts to dissuade Lukashenka from supporting Putin’s war risk legitimizing the discredited dictator and pose a threat to the future development of a democratic Belarus. This can already be seen in media coverage of the country, which has shifted from focusing on the Belarusian opposition to discussion of Lukashenka’s latest statements on the war.

Meanwhile, phone calls with Western leaders such as Macron and Zelenskyy position Lukashenka as a decision-maker and a potential partner in negotiations geared toward ending the war. This kind of engagement also underlines the fact that the democratic Belarusian opposition has no leverage over the military situation, whereas Lukashenka remains commander in chief, regardless of his international isolation and lack of legitimacy.

Western leaders need to be aware of these dangers as they seek ways to end the war in Ukraine. Rehabilitating Lukashenka may seem like a risk worth taking if it weakens Putin’s position in Belarus. However, this would mean ignoring the concerns of the democratic Belarusian opposition and may revitalize the Lukashenka regime, leading to further destabilization of the region for many more years to come.

Alesia Rudnik is a PhD Fellow at Karlstad University (Sweden) and a Research Fellow at Belarusian think tank The Center for New Ideas.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin shakes hands with Belarusian counterpart Alyaksandr Lukashenka during their meeting at the Vostochny Cosmodrome in Amur Region on April 12, 2022. (Sputnik/Mikhail Klimentyev/Kremlin via REUTERS)