The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) may prove to be one of the most transformative pieces of economic legislation in US history. The vast waves of investment coming to US shores throughout the last year bear out this possibility. One recent analysis estimated that between August 2022 and January 2023, over 100,000 clean energy jobs were created in the United States as a result of almost $90 billion invested in dozens of clean energy projects.

The domestic impacts of the IRA are undeniable. It is less certain what it means for the global energy transition. One year later, much work remains ahead to maximize the potential of the IRA. While US policymakers should consider the IRA’s long-term future and extend many of its provisions past 2032, officials must prioritize opportunities to align with like-minded allies overseas.

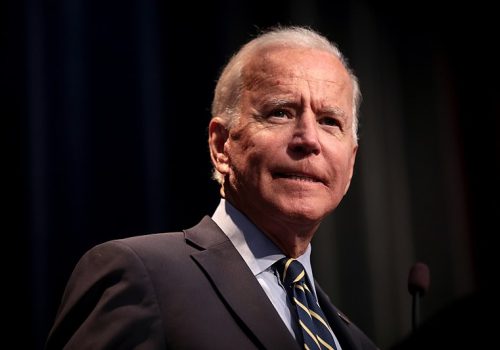

The IRA was designed to pair two central goals for the Biden administration: revitalize domestic industry while spurring a systemic transformation of the US economy toward a low-carbon, net-zero pathway. Undoubtedly, massive investments in key transition technologies within the world’s largest economy have global implications. New analysis suggests the IRA’s domestic provisions will ultimately reduce the cost curves for technologies like clean hydrogen and sustainable aviation fuels throughout the world.

However, these global benefits largely occur in the post-2050 timeframe—after the crucial midcentury date by when the world must achieve net-zero emissions.

The challenge

This problem reinforces the central challenge of the IRA-era—that the legislation represents only a fraction of the total investment needed to achieve a global net-zero pathway. The International Renewable Energy Agency recently forecast that investments in clean energy must more than quadruple to over $5 trillion per year to cap global temperature rise at 1.5°C. Even the most ambitious estimates of the IRA’s decade-long incentives fall far short of the investment needed to save the world. No single government, law, or system of incentives can meet this challenge.

The IRA, for better or worse, represents a major Western power turning firmly in the direction of a federally incentivized industrial policy. The United States did not start this trend–a centralized approach to industrial production of low-carbon technologies began in China, which dominates multiple clean energy value chains.

After the IRA, similar industrial policies are increasingly popular among long-standing allies of the United States. Earlier this year, the European Union (EU) announced its Green Industrial Plan, placing its Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) at the center of its own industrial strategy. Under the NZIA, the bloc aims for its strategic net-zero technologies manufacturing capacity to reach at least 40 percent of EU deployment needs by 2030. The bloc has adjusted its policies to allow its member states greater flexibility to incentivize private investors and match foreign subsidies, such as those available under the IRA. The Innovation Fund, one of the cornerstones of the revamped EU strategy, just announced that forty-one projects will receive grants worth €3.6 billion.

Japan’s approach is also illustrative. Last December, Tokyo unveiled its own Green Transformation (GX) Basic Policy, which aims for over $1 trillion in public-private financing opportunities over the next ten years. The GX Basic Policy will target areas including hydrogen, ammonia, carbon capture and electric vehicle (EV) adoption.

These developments suggest the world is at a crossroads, between a race to the top favoring widespread clean energy deployment and sustainable new businesses, and a race to the bottom for subsidization of nascent, untested decarbonization pathways. It is therefore critical to find ways to maximize the potential of the IRA and other emerging industrial strategies to achieve the fast-fading prospect of reaching net-zero by midcentury.

The IRA’s domestic future

The pathway towards that objective starts at home. US policymakers should articulate firm support for maintaining and perhaps extending the IRA. A key accelerator for private sector investment is de-risking; the certainty of a ten-year runway for the continuation of attractive credit, direct payment, and transfer opportunities has played an outsized role in driving the announcement of major new projects.

Importantly, these investments have been spread far and wide throughout the United States–blue states, purple states, and especially red states–with the emerging southern “Battery Belt” now common parlance. Recent estimates suggest that an astonishing $337 billion in investments for large solar, wind, and storage projects through the end of the decade will go directly to Republican-voting districts even as their congressional representatives attempt to unwind the law.

US policymakers—particularly within the GOP—should therefore dispose with notions that the IRA should be overturned in whole or in part and instead focus on collaborating with their colleagues to ensure that the legislation is working as intended and that any perverse outcomes are avoided or corrected.

An even more important step, however, is for Congress to consider the post-2032 timeframe and assess whether some of the IRA tax preferences should be extended beyond ten years. For private investors considering multi-billion-dollar projects—especially in nascent technologies requiring economies of scale—ten years is often insufficient to facilitate such vast commitments of capital.

Given the early success of the IRA, a sound analysis which assesses whether the benefits of extending the tax preferences warrant an additional five or ten years could be helpful. The subsequent legislative discussion must almost certainly wait until after the 2024 elections. The early success of the IRA could lead to a less polarized conversation in Congress, although much will depend on composition of that new Congress and the state of the US economy. But some confirmation of the IRA’s long-term staying power would enhance both its domestic economic and geopolitical benefits.

Federal agencies can assist the Hill in this task, particularly with updated and forward-looking regular assessments of how fast critical technology suites are progressing in comparison with the domestic climate targets of the United States. Such analyses could inform congressional action to adjust or extend key provisions in the law. They would also provide an opportunity to reassess if certain components are not working as intended.

Managing industrial policy on a global scale

Perhaps more importantly, maximizing the IRA involves a significant foreign policy component. The advent of the legislation produced manifold tensions between the United States and its overseas partners–particularly with respect to its EV domestic content provisions.

In March, the United States Trade Representative announced the US-Japan Critical Minerals Agreement intended to ameliorate concerns of Japanese automakers that their future EVs would be wholly shut out from qualifying for IRA tax credits. A similar—perhaps more expansive—reconciliation framework is under active negotiation between the United States and the European Union.

Despite these likely temporary concerns, the IRA has had substantial, positive foreign policy implications. The law has been a crucial tailwind for efforts to expand and diversify critical supply chains away from China. It represents the world’s largest economy turning firmly toward systemic decarbonization, with enormous incentives for developing and deploying under-developed technologies crucial to global net-zero. Given the evident domestic benefits, future US presidents are unlikely to turn away from the IRA outright—and certainly not from industrial policy more generally.

It is time for the United States and its partners to pursue a broader slate of harmonization opportunities to maximize the IRA’s benefits for all key stakeholders. A range of regulatory designs and metrics are proliferating for emerging low-carbon technologies including clean hydrogen, carbon capture and removal, e-fuels, and advanced biofuels.

The hydrogen example is instructive. While the exact requirements for meeting the “clean hydrogen” definition in the IRA are still in development, the European Union has already promulgated its own definition under the Renewable Energy Directive. Similarly, the IRA introduced a historic methane fee to complement upcoming regulations from the Environmental Protection Agency. Brussels, meanwhile, has finalized its methane strategy and pushed forward a legislative proposal to enhance leak detection and repair requirements throughout the bloc, impacting both domestic producers and external suppliers.

A collaborative approach in areas like these may already be underway with reports of a clean gas certification program under multilateral discussion. Broadly, alignment on standards, definitions, monitoring, and verification can ease and de-risk cross-border investment and trade in clean energy technologies globally. With so many decarbonization options moving rapidly from pilots to tangible scaling, there is no time like the present for friends to collaborate on how to regulate these new sectors. Equally important, however, is some sense of cooperation around the design and application of the various incentives now visible in national industrial policies throughout the world.

The time is now

In April, US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan emphasized that the Biden administration does not seek a race to the bottom with its allies. He pointedly noted in his remarks that the United States “is pursuing a modern industrial and innovation strategy—both at home and with partners around the world.” He argued that the United States seeks to strengthen and diversify global supply chains and the highest standards of good governance in order to “build a fairer, more durable global economic order, for the benefit of ourselves and for people everywhere.”

Given the tensions which have surrounded the IRA, these are lofty aspirations indeed–but they are not impossible through careful diplomacy. There is a precarious balance within the IRA between protectionism and the global scaling of clean technologies. However, if the end goals of the IRA are to dramatically grow the availability low-carbon technologies throughout the world and reduce Chinese domination of these industries, then like-minded allies should be able to come together and harmonize their incentive structures to promote beneficial competition. In-fighting amongst friends wastes precious time to build new economies of scale.

On its anniversary, the IRA, it appears, is here to stay–and so, it seems, is the global trend in favor of industrial policy approaches to the clean energy transition. The law will have profound international implications for the foreseeable future. The task now is to optimize the IRA and facilitate positive investment trends throughout the world as one piece of a much bigger puzzle. The IRA must be the beginning, not the endpoint, of a renewed global conversation around strategic energy transition goals. On that score, there is no time to lose.

David L. Goldwyn served as special envoy for international energy under President Obama and assistant secretary of energy for international relations under President Clinton. He is chair of the Atlantic Council’s Energy Advisory Group

Andrea Clabough is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center and an associate at Goldwyn Global Strategies, LLC

Meet the authors

Related content

Learn more about the Global Energy Center

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

Image: The U.S. Capitol