Over 600 million people in Africa lack access to energy, while the 46 percent of the population in Africa who do have access use less than all of Spain alone. Lack of energy access suffocates the continent’s economy, resulting in diminished growth compared to other developing regions. As the African population rapidly increases, the demand for reliable energy, secure jobs, and a sustainable future will increase in tandem.

Nonetheless, Africa’s development of its rich gas resources has become a controversial topic amid a global drive to reduce emissions and mitigate climate change. The development of African gas has the potential to enable the development of Africa’s broader industrial economy and support the transition to renewable sources, as well as the electrification of end use sectors. In the near term, gas developments offer an opportunity for the continent to industrialize to increase the economic growth and industrialization necessary for building out renewable infrastructure and securing investment through a far cleaner pathway than the coal-based industrialization from which developed economies rose.

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) recently released Africa Energy Outlook 2022 makes clear that energy access in Africa will be paramount to economic growth. Per IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol, “the biggest barrier in front of African economic development is lack of energy access.” Indeed, increasing energy access in Africa has become a top priority for the global community over the past decade. However, pandemic-driven economic pressures on unstable power markets and rising liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) costs have led to a 4 percent decrease in modern energy services (electricity and clean cooking fuels) between 2019 and 2021. This reversal of progress in meeting UN Sustainable Development Goal 7—affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all—should be a flashing red warning sign for Africa’s sustainable growth aspirations and should draw the attention of global policymakers and financiers in advance of COP27.

In recent years, international institutions have voiced commitments to divest completely from fossil fuel infrastructure projects. Examples include the US Department of the Treasury’s response to President Biden’s Executive Order 14008, ending support of direct investments in coal and oil projects abroad, and the European Investment Bank’s Energy Lending Policy, which phased out support for energy projects reliant on unabated fossil fuels. This has ignited the debate over whether it is possible for energy-poor sub-Saharan African nations without stable baseload generation or scaled transmission infrastructure to transition immediately to renewable power generation, and perhaps more problematically, to decarbonize industrial and agricultural processes.

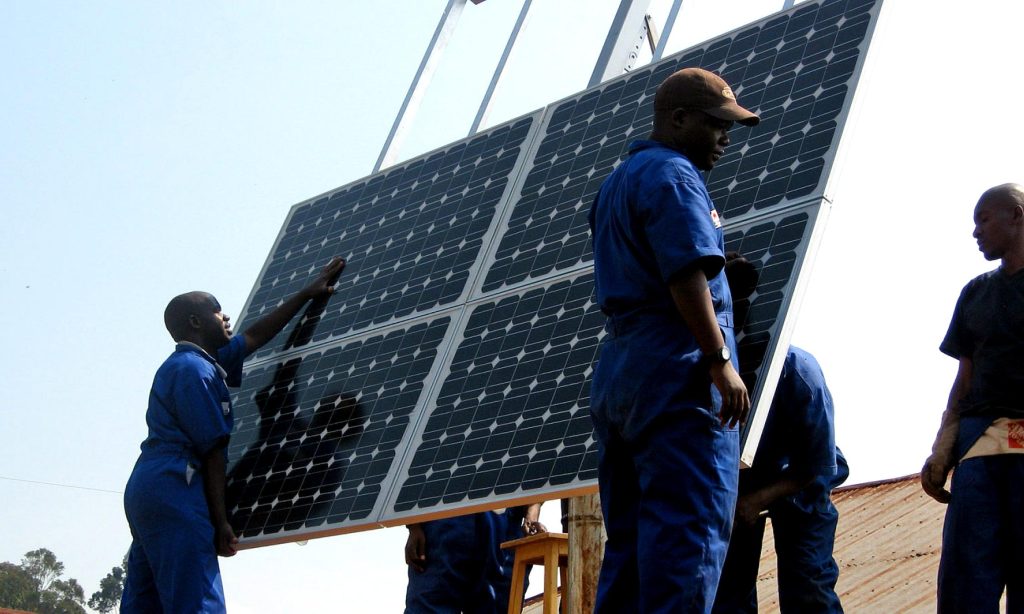

The answer to this conundrum is not cut-and-dry. Across the continent, energy needs and resources differ significantly. Households—the largest source of electricity draw in Africa—are one area where off-grid renewable solutions offer significant and immediate promise, particularly via distributed solar. This offers the opportunity for rural communities with little to no near-term hope for interconnection to develop localized power via off-grid solutions. On the other hand, substantial proportions of grid-supplied power in sub-Saharan nations such as Kenya and Ethiopia have come from carbon-free baseload generation due to a bounty of geothermal and hydroelectric resources.

But the resources for non-intermittent renewable energy deployment in Africa are unfortunately not universally abundant, and while resources such as solar and wind are becoming more cost-competitive and carry high potential, their intermittency still poses an obstacle. Without a significant expansion of solutions for baseload generation or the maturation and deployment of enablers like battery storage and transmission, renewables alone cannot yet provide enough power to smooth over supply and timing concerns and continuously meet demand by themselves. This dynamic is especially stark in sub-Saharan Africa where the most developed transmission systems regularly experience outages, and where issues surrounding cost-recoverability for electricity services disincentivize investment and sometimes generation itself.

Nonetheless, the prospect of an African continent with reliable access to energy in line with the IEA’s net-zero scenario is nearer than meets the eye. In fact, the best solution to reach the IEA’s Sustainable Africa Scenario (SAS)—Africa’s pathway for meeting the global net-zero scenario—is not to end all forms of fossil fuel production with immediate effect, but rather to allow the continent to fuel its economic growth with natural gas in the near term while accelerating deployment of renewable energy in tandem, with sights set on transitioning to an increasingly higher renewables mix in the medium to long term. Discoveries of gas in Africa from 2010 to 2020 represented 40 percent of all gas discoveries worldwide, raising the continent’s reserves to over 5 trillion cubic meters (tcm) of undeveloped reserves, and placing several African nations in the top 15 nations worldwide in terms of proven reserves. And importantly, if all of Africa’s untapped gas is fully developed, these resources would barely raise Africa’s emissions contribution at all, from less than 3 percent to just 3.5 percent of global energy-related CO2 emissions since 1890.

It remains troublesome to industrialize without the use of natural gas, particularly without paying a “green premium” which developed nations may be able to afford. Natural gas’ role in creating industrial process heat, and as a vital input for fertilizers and other chemicals, will allow Africa to forge an industrial sector which fuels economic development and increase agricultural self-reliance amid global food insecurity. Furthermore, projects underway in localities including Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Angola, Senegal, Mauritania, Congo-Brazzaville, and others could yield 90 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas, 30 bcm of which is projected to be available for export that will produce more revenue for sub-Saharan governments increasingly burdened by debt.

However, natural gas development will not place Africa on a path to meet its climate or development goals without additional action. Renewable energy will be needed to accelerate progress to expand energy access to hard-to-reach communities and cement the continent’s role in a global net-zero future.

Under the SAS, 80 percent of Africa’s primary generation will be derived from renewable sources. Possessing 60 percent of the world’s best solar resources, Africa has a pathway to dramatically reshape its energy sector to a low-emissions and reliable system. But though the continent is rich in renewable energy resources, only 1 percent of global installed solar capacity is in Africa.

The biggest barrier to building the infrastructure necessary to realize the SAS is undoubtedly access to capital. Not all markets in Africa are ready for immediate large-scale investments to deploy intermittent renewable energy systems due to the lack of early-stage infrastructure to support them. There is a pressing need to first foster economic maturation in sub-Saharan nations via industrial growth and electricity access, leading to the infrastructure development needed to meet and stimulate energy demand and build economies of scale while prioritizing low-carbon and reliable energy sources.

To empower this transition, the role of gas in providing baseload generation and industrial process heat will be crucial, providing a clear impetus for Africa to fuel its growth by developing its gas resources. A growing, burgeoning, industrial Africa has the potential to bolster the investor confidence that will be needed to infuse the continent with international capital and ultimately deploy the renewable energy systems needed to achieve an 80-percent-renewables future.

In response to these challenges, the private sector has played an important role in accelerating deployment of renewable energy projects throughout the continent. In hard-to-reach communities, micro-hydro or mini-grid projects present a more viable and promising future to increase energy access for rural populations rather than grid-scale generation and infrastructure. For example, since the commencement of South Africa’s Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement (REIPPP) program, independent power producers in South Africa have started ninety-five renewable energy projects, achieving an estimated capacity of 3.27 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy once the projects are fully operational. The GET FiT programs in East African countries have supported the deployment of renewable energy in Uganda and Zambia.

Larger-scaled examples include the 2.4 GW Batoka Gorge hydroelectric power project for use in Zambia and Zimbabwe and the 6.45-GW Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Morocco expects to generate 52 percent of its generation capacity from renewable energy by 2030, and renewable energy already generates approximately 90 percent of Kenya’s power.

But turning these examples into a continent-wide reality will hinge on finance, and private capital has a much larger role to play going forward; in 2018, only 12 percent of the continent’s infrastructure financing was provided by the private sector, with African governments themselves eclipsing this level of investment three times over. Achievement of the full SAS will require significantly heightened investor confidence in African markets to spur a wholescale escalation of Africa’s access to international capital for the purpose of building energy infrastructure. A figure which increases annually to reach $190 billion between 2026 and 2030 would suffice to put Africa on track to meet the provisions of the SAS by attaining an energy mix which is at least 80 percent renewable, supplemented by gas for industry and baseload power. For a continent with primary energy demand which is expected to grow as much as fivefold by 2050, the costs of not making these investments are ultimately likely to be far greater.

William Tobin is a program assistant at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.

Maia Sparkman is an assistant director at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.

Meet the authors

Related content

Learn more about the Global Energy Center

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

Image: Workers installing a solar panel in Rwanda. (Walt Ratterman, USAID, CC0 1.0) https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/