Why data governance matters: Use, trade, intellectual property, and diplomacy

Introduction

Open societies, including those in North America and Europe, face sharp challenges in coordinating their approaches to data, the “black gold” of the 21st century. The Atlantic Council’s GeoTech Center has focused significantly on solutions to those challenges and their benefits, including initiatives to employ data for good in the COVID-19 pandemic and data trusts for food and other cross-sector, multinational issues.

Data governance may be a somewhat hackneyed phrase, but to the extent that data is governed, that governance is a byproduct in part of the governing of the internet. The World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) in 2005 defined governance for the internet as “the development and application by governments, the private sector, and civil society, in their respective roles, of shared principles, norms, rules, decision-making procedures, and programs that shape the evolution and use of the Internet.” This UN-sponsored summit also formed the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) for an open discussion of the future of internet governance, with no commitments, yet thus far the forum has accomplished nothing of operational significance.

Any discussion of data governance inevitability must address different visions of the internet and the future. Conceptions range from Silicon Valley’s open internet and free flow of data with the faintly anarchist motto “data wants to be free” to Washington’s market-based internet—if data is the new oil, then let’s drill it. There is the EU’s bourgeois internet that seeks to maximize freedom for online users but under tight government regulation. Beijing’s authoritarian vision of the internet is the Great Firewall, a tightly-controlled collaboration between government monitors and the technology and telecommunications companies enforce the state’s rules. Moscow’s mule model aims to disrupt the international order while taking steps to test the independence of its internet by routing all traffic through exchange points controlled by its national regulator, Roskomnadzor, thus temporarily cutting itself off from the world-wide-web, while India’s vision is to make sure it is not colonized again, this time by international firms managing its citizens’ data.

Add to this the fundamental cultural differences between various countries that influence their policies and approaches. For example, privacy has different meanings in China, the United States, and Europe. Since the internet is a global network of networks, national internet policies have global ramifications.

Issues in governing the digital domain overlap, cut across policy areas, and even conflict. For example, efforts to safeguard privacy conflict with national security requirements. Digital trade touches on all other policy areas and conflicts with some. Laws, standards, and norms that are required to safeguard universal values or global and national interests, such as the environment, human rights, and privacy, could limit the scope of free digital trade. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) sets out three policy goals in the digital economy: “(1) enabling the internet; (2) boosting or preserving competition within and outside the internet; and (3) protecting privacy and consumers.” It goes without saying that the three can conflict with one another.

Global data and internet governance represent a scattered, multi-stakeholder, bottom-up, and driven by loose coordination among various players. Data governance can be thought of as incorporating a triangle of individuals and their privacy, nation-states and their interests, and the private sector and its profits. Its current status and prospects might be thought of along several lines of activity, which are interrelated but, for the sake of clarity and with some danger of oversimplification, are discussed in the following different sections: privacy and data use; regulating to police content; using antitrust to dilute data monopolies; self-regulation and digital trade; intellectual property rights; digital diplomacy.

Privacy and data use

Historically, the focal points of legislation relating to data efforts have been privacy (what will happen to personal information collected by websites), accuracy (how users will know when something posted is false), decency (how users will be protected from harmful and hateful language or images), and stewardship (where and by whom personal information will be stored). The root of the challenge is that the tech giants have stumbled onto a business model that is both hugely profitable and hugely predatory, for it depends on collecting, using, and selling personal information about users. The more information, the better—it enables sites to better target the tastes and desires of people to whom they wish to sell or advertise something.

In a striking demonstration of how much global geometry has changed, neither of the two most noted pieces of legislation about data privacy so far has been enacted by a nation-state. Most important is the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), enacted in 2016, scheduled to come into effect in 2018, and building on previous EU data protection rules. GDPR stipulates how sites are to collect and process data from people who reside in the EU, regardless of where the sites are located. Users who visit sites must be told what data the site collects from them and then must be asked to explicitly agree to its collection by clicking on an “Agree” button or some similar action. The GDPR applies to data beyond that collected from customers, including, perhaps most importantly, to human resources records of employees, information that will affect their future job prospects. The GDPR also requires that personally identifiable information (PII) be either, in the awkward language of today’s information world, anonymized—that is, rendered anonymous—or pseudonymized, in which a user’s true identity is replaced with a pseudonym.

The other major law is the California Consumer Privacy Act, or CCPA, which came into force at the beginning of 2020. In contrast to the GDPR, which in effect requires consumers to opt into data collection, the CCPA only lets consumers opt-out. In that sense, it is less stringent than the GDPR, which permits people to, in effect, cut off the data stream at the source by not granting the right to collect. The CCPA gives users the right to ask a company to produce all the personal information it has gathered on them over the years, as well as all the categories of businesses it got that information from or sold it to. If a consumer asks, companies must delete all the information they have on that consumer, and if the company shared personal data with another company, they must tell that company to delete it too.

The EU’s intention to create a much stronger and more robust privacy framework has been apparent since the early days of the web. The EU has signaled that its understanding of the right of privacy is not only different from many other nations but also a high priority in its policymaking. The GDPR was preceded by the 2002 ePrivacy Directive, the landmark 2014 decision by the European Court of Justice on the Right to be Forgotten, and the 2017 ePrivacy Regulation proposal. The GDPR shifts the dynamic of personal data use towards users by giving them ultimate control over the processing of their data.

The transatlantic difference was illustrated by one experiment just before the GDPR came into force when researchers in United Kingdom and the United States asked for information about the data being held about them. When they asked the marketers, the researcher who lived in Britain got “200 rows of data containing details about my personal life” and “343 rows of data on the consumer marketing segments I’ve been assigned.” The researchers in the United States was furnished with “1 row of data indicating I once read an article on Forbes.com” and noted that “the Quantcast spokesman added that the company responded to data access requests under European law. So sending me any data at all has been an error—because consumers in the United States do not have a comprehensive right to obtain copies of the data held by American companies.” From Amazon, the British resident received “order history, credit card information, prime subscription data addresses, wish list items, and devices used to access amazon services,” while the American resident received only order history.

The GDPR both sought to be and is being used as a template for other countries. Indeed, 132 out of 194 countries have put in place some legislation to secure data and privacy. Brazil, Japan, and South Korea have followed Europe’s lead, and, in general, the EU has set a higher standard for not only privacy but also the enforcement of antitrust laws, leading to tougher tax policies on those companies. In contrast, the United States, especially under the Trump administration, has taken a different path, with talk but little action about regulating the tech industry. Instead, it has sought to protect the big tech companies from taxes in foreign countries and limit regulation while at the same time protecting them from Chinese competition.

The difficulties of legislating borderless activities have been underscored by the OECD’s struggle to negotiate a global consensus on digital taxation. The United States dropped out of the discussions in June 2020—apparently fearing that the “big five” companies were targets—and opened investigations into several countries that have imposed or are considering digital taxes. The result is likely to be the further balkanization of this aspect of internet governance, with individual countries imposing levies and thus pitting themselves against the United States, which will in turn, use policy carrots and sticks to get taxes ended or diluted.

Since European countries have been in the lead in pushing digital taxation, trans-Atlantic relations will suffer as a result. For instance, in 2019, France levied a 3 percent tax on revenue that companies receive from providing goods and services to French residents over the internet even if the companies had no significant presence in France. In response, the United States began an investigation into whether that discriminated against the big five and other corporations. In early 2020 the two countries declared a pause, with France agreeing not to collect the taxes while the OECD discussions continued. However, when the United States left those negotiations, it proceeded to announce tariffs on selected French goods in retaliation for the taxes.

Data protection and privacy laws do not usually require stewardship in the form of retaining data, and most data protection laws would ultimately favor not storing of copies entirely. However, stewardship laws place restrictions on data flows, limiting data transfer over national borders to only places with adequate safeguards of data in place. The concepts of privacy and cross-border data flow have given rise to three terms: “data residency,” “data localization,” and “data sovereignty,” often used interchangeably and creating confusion.

Data residency is a site’s choice for locating its data warehouses, a decision based on factors that range from evading or benefiting from laws, regulations, and tax regimes to convenience and subjective preference. Once the location is selected, data is subject to local data residency laws, also known as data sovereignty. These laws are usually designed to protect government interests and often cover data likely to be core to business needs. They allow data transfer over the border but demand sites keep a local copy available to the local government for inspection; an example is India’s draft Personal Data Protection Bill.

Data localization, mandating that data acquired within a nation’s borders remain there, is the most restrictive of the three concepts, and its prevalence is growing rapidly. The Founder and CEO of Calligo, Julian Box, describes the concept as one “almost always applied to the creation and storage of personal data, with exceptions including some countries’ regulations over tax, accounting, and gambling.” Here, the law prevents data from crossing the border. Russia’s Personal Data Law (OPD-Law) is a case in point: storing, updating, or using data on Russian citizens must be confined to data centers inside Russia. For skeptics of these residencies and especially localization laws, they use securing the cyber realm or protecting individual privacy as a cover for what is really trade protectionism, an issue covered in more depth in the trade section of this paper. When data is confined to national silos, the potential of that data is limited, and the ultimate result could be a splintering of the web—a “splinternet” in the jargon of the trade.

The challenge of regulation—that internet technologies change quickly while governmental processes are deliberative, hence slow and all the slower if the action sought involves several nations requiring a treaty or international agreement—also afflicts legislation. As a result, there is always the inherent risk that by the time a regulation is enacted, it will be obsolete or, worse, counterproductive.

The challenge is illustrated by one old piece of legislation that has come under new scrutiny: Section 230 of the US Communications Decency Act of 1996. Enacted in the early years of the web, its goal was to promote innovation, not to protect decency or privacy. As a result, the regulatory regime it established was permissive: providers were given broad immunity from lawsuits for words, images, and videos posted on websites. It is increasingly the target of criticism across the political spectrum. President Trump and the political right believe that Twitter, Facebook, and their kin muzzle conservative views, and that without the 230 protections, voices who felt they had been denied a platform could have sued. The other side of the political spectrum, including House Speaker Pelosi, maintains that Section 230 has permitted a slew of disinformation and harassment, and absent it, they argue, the sites would have to be much more proactive in policing their content. A 2019 bill introduced by Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) proposed ending legal protections for tech companies that didn’t agree to an independent audit ensuring that there was no political bias to their monitoring of content, .

Comparing the experiences of other countries in regulating internet content is instructive. India has the second oldest legislation on the topic, passed in 2000, which, like the US Communications Decency Act of 1996, gave sites safe harbor from liability but which, unlike the US act, did so only if the site met stipulated conditions. Those conditions were extended in 2011 to include more types of content that should be taken down once a website was made aware of their presence by users. Another bill, proposed in 2018 but not yet enacted, would require platforms to be proactive in monitoring, taking down illegal content within twenty-four hours when flagged by court order or a government agency.

At the same time, in 2000, the EU issued its own e-commerce directive, which paralleled the Indian approach by providing a safe harbor from liability provided the site was a “mere conduit” that removed the highlighted material once it was brought to their attention. As in the United States, technological change has scrambled the debate, leading to calls for revision of the directive. Unlike in the United States, however, EU states have moved ahead on their own. For example, Germany’s 2017 Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG) and France’s 2020 “Fighting hate on the Internet” bill clarify the conditions under which tech platforms can be fined for disseminating illegal or harmful content. When users identify such content, the platforms are given only a brief period—twenty-four hours in both countries—to take it down. The laws stop short of requiring constant monitoring, but they surely will lead to much more restrictive moderating by the sites themselves.

In 2019 the United Kingdom, soon to leave the EU, released a government white paper that goes well beyond the EU’s provisions. In addition to requiring that platforms to have some mechanism for taking down unlawful content as the EU does, it calls for an undefined “duty of care” that presumably would include what is still not allowed within the EU—proactive and constant monitoring, all supervised by a new regulatory agency with the ultimate authority to create and enforce best practices, including by issuing fines and even imposing prison sentences.

Adapting to the new realities is not just a challenge for the United States: the law France passed required sites to take down hateful content flagged by users and to do so within twenty-four hours, but the French Constitutional Court ruled in mid-2020 that putting the onus only on the tech companies without a judge and with heavy fines would encourage the platforms to indiscriminately remove content without proper evaluation, consequently infringing on free speech.

Self-regulation and digital trade

Self-regulation by the tech giants themselves can represent a potential cat-and-mouse game with governments, with the companies acting on their own lest they are forced by regulators to do something even less desirable from their point of view. According to the Internet Governance Forum, “public and private regulation often overlap: the term ‘regulated self-regulation’ refers to an arrangement in which companies regulate themselves, while the state oversees to ensure that the system is functioning as required.”

A major milestone in self-regulation was reached in 2019 when Google announced that it would allow users to automatically delete data on their web searches, location history, and requests made to the company’s virtual assistant. In mid-2020, it announced that for new accounts, it would automatically delete location history, records of web and app activities, and voice recordings after eighteen months.

For skeptics of self-regulation, the changes are mostly window dressing. Facebook’s internal oversight board is cited as an example. It is meant to deal with the hardest cases but will hear only individual appeals about specific content that has been taken down – and will be able to hear only a fraction of those appeals. Content that has been left up will not be reviewed, nor will the board have authority over Facebook’s advertising or the collection of data that makes Facebook ads so valuable. Finally and most importantly, Facebook’s algorithms that determine what content is seen most will remain intact.

The financial services industry offers one hybrid model for regulation: FINRA, licensed by Congress but a private non-profit organization. Its mission is, in the language of its own website, “making sure the broker-dealer industry operates fairly and honestly. We oversee more than 634,000 brokers across the country – and analyze billions of daily market events. We use innovative AI and machine learning technologies to keep a close eye on the market and provide essential support to investors, regulators, policymakers, and other stakeholders.” The tech companies themselves could create something similar with guarantees of independence in judgments and ideally with a license from Congress.

Recent debates about self-regulation have focused more on content than user data. There surely is a political overtone to much of the disinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic, but at least the task for the tech giants was relatively straightforward: to warn users of incorrect or misleading statements, especially dangerous ones, and to take those down while guiding users to helpful information. Twitter, for example, acted early in the pandemic to try to assure that people looking for information on the virus were taken to reliable sources, like the World Health Organization or national health agencies, not conspiracy sites or outlets that had been identified as spreading “fake news.” As the crisis developed, Twitter’s algorithms detected and flagged harmful falsehoods for removal—for instance, sites that were denying or advising against following official advice or promoting unproven “alternative” treatments.

As the 2020 elections loom, political advertising and the handling of content from politicians, in particular the president, have been controversial. Facebook has maintained the view that content that is false or divisive from an important political figure should not be policed because it is in the public interest to view it. In contrast, Twitter earned Trump’s scorn by beginning to fact check and add warnings to his tweets. In June 2020, Facebook, under pressure over hateful speech from its largest advertisers, including Coca-Cola and Starbucks, said it would attach labels to any posts that discuss voting, directing users to accurate voting information in an effort to prevent disenfranchisement in November. It also expanded the category of hateful language to be prohibited. Posts that violate those rules but are from senior politicians, like President Trump, will receive a label indicating the post was deemed noteworthy enough to remain.

As data became not just a precious commodity but also a source of power, data flows across borders became important for global trade and subject to the existing global trade system. That system was created after World War II to promote global prosperity by reaching the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947. GATT reflects the conviction that free trade will result in global good, a belief as old as Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations(1776). The goal is to lower tariffs, quotas, and other barriers to global trade through unilateral or multilateral agreements. GATT rapidly became the premier multilateral trade arrangement, and it succeeded in lowering average tariffs among industrial countries from around 40 percent at the start to about 5 percent today.

In 1995, the GATT was subsumed by the World Trade Organization (WTO), which currently has 164 members and 24 observer governments. It is where members negotiate reductions in trade barriers and mediate disputes over trade matters. The WTO governs four global trade agreements: the GATT, the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), and agreements on trade-related intellectual property rights and trade-related investment (TRIPS and TRIMS).

GATT signatories must extend most-favored-nation (MFN) status to all WTO members. Slightly oddly given the language, MFN status means that no member’s goods should be subject to greater tariffs in foreign markets than the lowest applied to any foreign country competing in that market. Most-favored-nation has been replaced in US legislation with “normal trade relations (NTR),” which has the same meaning. However, GATT permits two exceptions from NTR: free trade areas, which let members eliminate tariffs on trade with each other but give them the right to set tariffs on non-members, and customs zones, which also eliminate tariffs among members but sustain a common tariff on countries that are not part of the zone.

Over the last few decades, unsurprisingly, digital trade has become a major part of trade flows. A joint Huawei-Oxford Economics report found that “the digital economy is worth $11.5 trillion globally, equivalent to 15.5 percent of global GDP and has grown two and a half times faster than global GDP over the past 15 years.”

What constitutes digital trade varies depending on which country one examines. The US International Trade Commission (USITC) defines it as “the delivery of products and services over the internet by firms in any industry sector and of associated products such as smartphones and internet-connected sensors. While it includes the provision of e-commerce platforms and related services, it excludes the value of sales of physical goods ordered online and physical goods that have a digital counterpart, such as books, movies, music, and software sold on CDs or DVDs.”

The absence of a globally agreed-upon definition of digital trade means there is also no set of international law to govern it and that key issues are treated differently in different trade agreements. The WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), for instance, predates the explosion of the global data flows across the internet, but since it does not distinguish how services are delivered, it includes digital services. Most other agreements, however, cover physical goods and intellectual property and make no provision for digital goods. However, since 1998, WTO countries have agreed on a series of moratoriums on imposing customs duties on electronically transmitted services and goods, like e-books and music downloads.

For its part, the WTO Information Technology Agreement (ITA) seeks to reduce tariffs not on goods traded on the internet but on the goods that enable it, aiming to lower costs all along the value chain. The original agreement was reached in 1996 and was expanded to encompass further tariff cuts beginning in 2016. Its fifty-four member countries are responsible for more than 90 percent of global trade related to the goods covered. Some member countries like Vietnam and India chose not to join the expanded agreement; however, as with the original ITA, all WTO members receive the benefits of the expanded agreement on an MFN basis. ITA members will continue to review the agreement to see if emerging technology requires covering additional products. Tariff cutting through the ITA has expanded trade in the technology that is the basis of digital commerce, and the agreement neither tackles nor aspires to tackle the non-tariff barriers (NTBs) that limit trade.

There are increasing concerns about the WTO’s ability to keep up with the mushrooming digital economy and digital trade. GATS is an example—while it does cover electronic trade in services, it does so on what is called a “positive list” basis, wherein each member must opt into a specific service sector for it to be covered. As a result, coverage across members varies, all the more so because many of today’s digital goods and services had yet to be created when the agreements were reached. To address this shortcoming, the WTO’s Committee on Specific Commitments is examining how both new digital services and new regulations, like data localization, could be addressed by GATS.

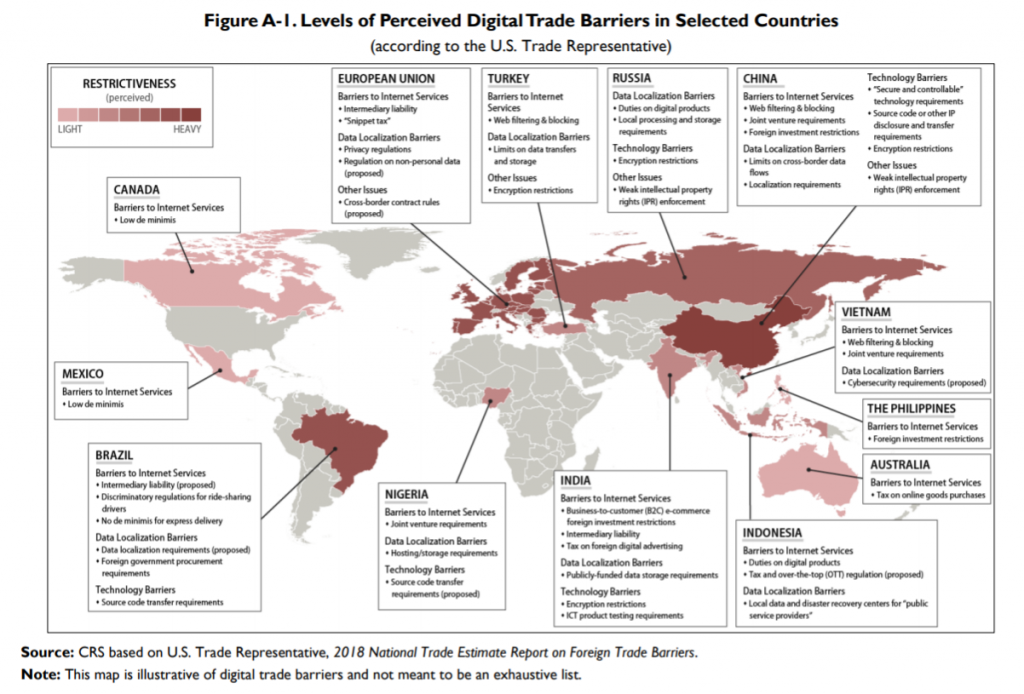

The historical focus of trade policy has been visible barriers like tariffs and quotas. Efforts to reduce non-tariff barriers (NTBs) aim at broader governance issues, ranging from transparency and investor protections to restrictions on investment, foreign ownership, or people’s movements. In the digital domain, privacy protection or national security arguments—often motivated by a different vision of the internet in the case of the EU, as part of a grand geopolitical strategy in the case of China, or a mixture of the two—are used to justify data localization measures.

As an example, from one perspective, China’s insistence on internet sovereignty and full government control could be seen as a legitimate effort to control harmful or hateful information. Yet, from another perspective, it is an NTB that limits foreign access to China’s digital market, thus advancing Chinese corporations and limiting China’s reliance on foreign technology.

By the same token, data localization measures also could be seen as NTBs, for they explicitly aim to limit flows across borders by requiring companies to store and process data within national borders. They reduce efficiency by increasing costs and decreasing scale, effects that migrate through the entire global supply chain. The data “silos” created by the localization requirement become valuable targets for a cyberattack, and localization discourages small- and medium-sized companies from moving to cloud computing, which denies revenues to the largest global providers, all American companies: Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and IBM.

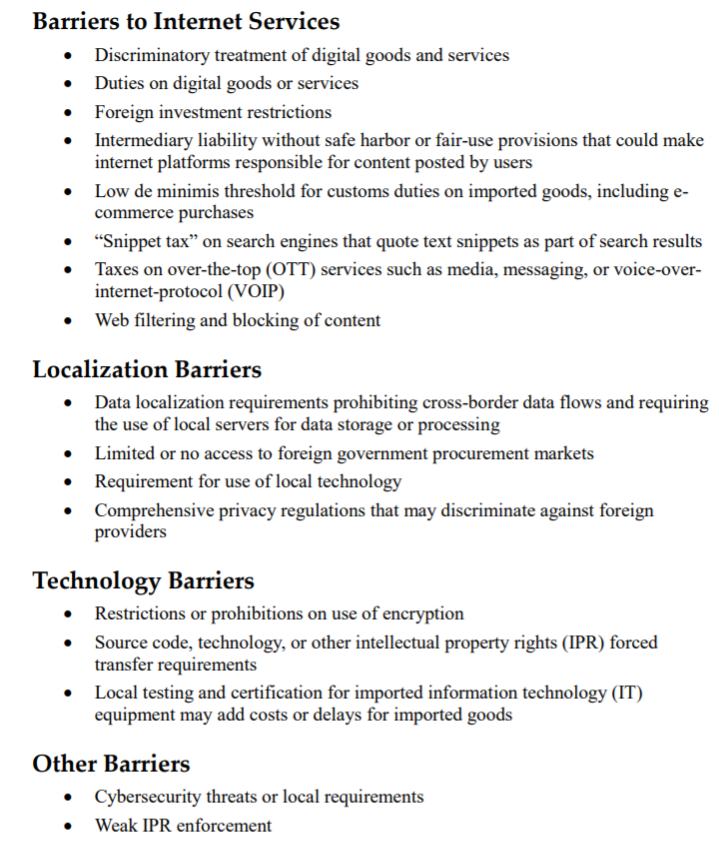

Other localization provisions that act like NTBs are familiar from trade-in goods—for instance, the obligation to use local content and vendors for both hardware and/or software in order to operate or qualify for government contracts, or to partner with and transfer technology to local companies. A CRS report, Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy, lists the following as additional NTBs affecting digital trade: “High tariffs, localization requirements, Cross border data flow limitations, IPR infringement, Discriminatory, unique standards or burdensome testing, Filtering or blocking, Restrictions on electronic payment systems or the use of encryption, Cybertheft of U.S. trade secrets, [and] forced technology transfer.” Finally, net neutrality is an attempt to prevent NTBs by safeguarding content providers from discrimination that platforms may impose on their location.

In December 2017, over seventy WTO members reached an agreement, as described in a WTO press release, to “initiate exploratory work together toward future WTO negotiations on trade-related aspects of electronic commerce.” In January 2019 the statement was adopted by the WTO’s seventy-six partners, including both richer countries and emerging economies. India did not join because, as described by the CRS Report Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy, it preferred “to maintain its flexibility to favor domestic firms, limit foreign market access, and raise revenue in the future through potential customs duties.” The negotiating parties despite their differences in the scope of the negotiations have agreed to continue.

In recent years, multilateral agreements have come under attack by anti-globalists who see them as serving the interests of multinational corporations, not people. This opposition has created pressure to include various standards in trade agreements lest unrestricted trade should create a “race to the bottom” in labor, environmental, and other standards as cost-cutting multinational corporations roam the globe in search of cheap labor and pliable regulations. The risk is that standards will become a pretext for protectionism by the rich countries. In those circumstances, it is no small wonder that WTO negotiations have been stalemated: not only are the arguments complex, and the application of traditional trade policies to the digital economy unclear, but major players— the United States, the EU, and China—differ sharply in their approaches.

As a result, bilateral and regional trade agreements have become popular. One such agreement joins the United States and the EU, whose cross-border data flows are the largest in the world. The two also account for a large portion of each other’s e-commerce trade and almost half of each other’s service exports that are delivered digitally. Yet, different conceptions of data, trade, and privacy have driven a wedge between the two entities, forcing them to enter negotiations in 2013 over a vast array of digital and IPR trade topics that have yet to conclude.

Intellectual property rights

The internet and digital technologies have been particularly challenging when it comes to the protection of present intellectual property rights (IPR)—patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets. IPR are legal rights that grant exclusivity of use to inventors and artists for a limited time.

In recent years, IPR infringement has surged considerably, mainly because digital technology makes counterfeiting and its distribution cheap, easy, and hard to trace. Cyber-enabled theft of trade secrets has been particularly concerning for the United States. It is hard to know the exact figure for the IP loss, but it is a major part of the $600 billion estimated by the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property Policy Recommendation (2018).

While protecting IPR is critical to promote innovation, if IPR policies are too strict they could present obstacles to data flows and digital trade. To overcome this, US law introduced the “fair use” doctrine, which allows for unlicensed use of protected works under certain conditions. International IPR treaties date back to the nineteenth century. The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (1886), is the first copyright multilateral convention. The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) of 1970 is another international patent agreement. The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) (1995) was founded on existing treaties. It strived to balance private rights against broader public benefits and established a minimum required standard for protecting the intellectual property for the members of the WTO.

The TRIPS Agreement is comprehensive and covers all forms of IP including copyrights, trademarks, patents, and trade secrets. Like GATS, it predates the internet era and has no direct reference to the digital ecosystem. However, it serves as a base for IPR provisions in ensuing trade negotiations, often identified as “TRIPS-plus.” Digital Trade and U.S. Policy explains that “TRIPS incorporates the main substantive provisions of WIPO conventions by reference making them obligations under TRIPS. WTO members were required to fully implement TRIPS by 1996, with exceptions for developing country members by 2000 and least developed country (LDC) members until July 1, 2021…for pharmaceutical products, the implementation period has been extended until January 1, 2033.” The TRIPS provision on computer programs references the WIPO Berne Convention to treat computer source and object code as literary works and protected. The TRIPS provision on data, as noted in its WTO overview, “clarifies that databases and other compilations of data or other material, whether in machine-readable form or not, are eligible for copyright protection even when the databases include data not under copyright protection.”

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) is shaped by the TRIPS Agreement and serves as the administrator and primary forum for IPR issues in the digital realm. The WIPO “Internet Treaties” consists of the Copyright Treaty and Performances and Phonograms Treaty. The Digital Trade U.S. Trade Policy report summarizes the laws, writing that they “clarify that existing rights continue to apply in the digital environment, to create new online rights, and to maintain a fair balance between the owners of rights and the general public.” It provides for legal protection against circumventing Technological Protection Measures (TPMs), including encrypting, as well as removing or modifying the encoded rights management information (RMI), which makes it possible to trace the usage of the information. National governments are left to work out the legal details for the ISP obligations. The WIPO Internet Treaties’ implementation in the United States takes place through the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA) (H.R. 2281) that offers “safe harbor” to ISPs that “unknowingly” transmit copyrighted information. Other important agreements include the Protocol Relating to the Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks (known as the Madrid Protocol) (2003) and the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) (2011).

The Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy report also notes the significance of the new EU Copyright Rules adopted on April 15, 2019, to update copyright laws for the internet era and provide a balanced and fair content marketplace. Their directive on “neighboring rights” reimburses news publishers and journalists for the online usage of content. Google and other news aggregation platforms must obtain licenses from content providers to showcase content less than two years old. In the absence of a license, agreement platforms must make best efforts to remove copyrighted materials once notified, though only older and more established platforms are subject to the requirements. While the US publishing industry supports the new rules, content-aggregators have expressed concerns about degraded market efficiency.

When the US Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) help initiated the internet in the 1960s, it could hardly have imagined what its creation would become. Once the ARPANET became the public Internet in 1989, the network created a new world and became the dominant feature of twenty-first-century society, commerce, and national security—one that led to immense strength but also generated great vulnerability. Neither the government nor the private sector anticipated the speed of this technological revolution and the challenges it would pose. As a result, the internet still operates on protocols developed in the 1960s that are inherently vulnerable. These vulnerabilities are exploited for crime, espionage, and warfare. Cybercrime alone is predicted to cost the global economy $6 trillion by 2021. Cyber attacks threaten not just to business operations and supply chains, but also to financial and communications infrastructure, national security, privacy, trade, and commerce.

As for espionage or cyberwarfare, costs are hard to estimate, but the practice is widespread. At the turn of the twenty-first century, governments including the United States’ realized that they could use their new cyber capabilities to go beyond spying. They could covertly insert code or information in order to influence, disrupt, or destroy. The list of operations is long: by the United States and Iran against each other, Israel and Iran against each other, Russia against Estonia, Georgia, and Ukraine, and so on. Particularly salient were attacks by Russia against at least the US democratic process and the subsequent American retaliation against the Russian Internet Research Agency responsible for the operation, Iran against Saudi Arabia, and North Korea against Sony Pictures and the global banking system. Worse, there is the possibility that the states conducting cyber offensives may lose control, inadvertently damaging third parties. There is also the ever-present risk of miscalculation and accident from which escalation can ensue.

States involved in espionage, like criminals involved in crime, try to hide their identities, or least maintain plausible deniability. Yet, when attribution is possible, nations can prosecute those responsible for cybercrimes but not those responsible for espionage. Such activities remain the murky domain of clandestine operations.

Even when a no-espionage agreement is achieved, it is often ineffective. The 2015 Sino-American agreement on cybersecurity and trade secrets is illustrative. It pledged that “neither country’s government will conduct or knowingly support cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property, including trade secrets or other confidential business information, with the intent of providing competitive advantages to companies or commercial sectors.” The G-20’s November 2015 communique states that “In the ICT environment, just as elsewhere, states have a special responsibility to promote security, stability, and economic ties with other nations. In support of that objective, we affirm that no country should conduct or support ICT-enabled theft of intellectual property, including trade secrets or other confidential business information, with the intent of providing competitive advantages to companies or commercial sectors.” Section 301 Investigations into China’s alleged infringements of US IPR began, and by December 2018, US Assistant Attorney General John C. Demers announced that over the previous seven years, 90 percent of Justice Department’s espionage cases and two-thirds of trade secrets cases were connected or attributable to China. This escalated the trade war, increasing tariffs for both sides.

By contrast, in dealing with cybercrime, countries enter multilateral and bilateral treaties and agreements as well as public-private partnerships and engage in setting norms. Still, it is not an easy ride, for there are many conflicting beliefs, such as the differing visions of the internet that range from an open and free market to authoritarian and controlled one, and the elusive balance between cybersecurity on one hand and privacy, anonymity, and encryption on the other.

Digital diplomacy

Looking to the future, the ubiquity of data and of AI to process it will transform diplomacy. That transformation might be conceived of in three categories—data in diplomacy, diplomacy for data, and data for diplomacy, or, respectively, the use of data to advance or constrain diplomacy, negotiations about how data will be handled across borders, and data as a way to enhance diplomatic capability. The second category, diplomacy for data, has run through this entire paper, but it is worth saying a word about the other two.

Concerning data in diplomacy, formal diplomacy has long distinguished between Track I discussions between government officials and Track II discussions involving a wider set of experts or stakeholders outside the government. Nations often resort to Track II when formal Track I negotiations are not available or are deemed a step too far. Recently, the term “Track 1.5” has become popular, referring to governments’ discreet participation through a third party or organization.

The increasing availability of data will enlarge both the number of non-governmental actors who influence formal diplomacy and the purposes for which that data is employed. Imagine, for instance, if ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia during the 1990s had occurred in the presence of ubiquitous cellphone cameras. Fresh gravesites, such as those in the massacre at Srebrenica, would have been documented immediately for the world. More data for more participants will make formal diplomacy messier and less predictable: witness the 2013 disclosure by Edward Snowden of National Security Agency’s surveillance programs, which he justified as whistle-blowing and which did, in the end, play some role in the public pressure that lead to the GDPR.

In the third category, data for diplomacy, data experts and increasing amounts of data will create new relationships and thus new opportunities for diplomacy. In principle, this should be a great boon for the effort to adapt the existing international architecture to the emerging world.

Looking ahead

The challenge of reimagining future architecture is global, not national, for the combined impact of big data, AI, ML, and IoT is escalating geopolitical tension. Today, data ownership has become critical to the balance of power, and the impact is exacerbated by the prospect of machine learning that mobilizes big data beyond human capacity and by its potential to generate intellectual property. Unlike the tangible and production-based economy, which encourages globalization and free trade, the intangible data-economy seems to favor protectionism. The collective impact is redefining geopolitics with no precedent, as manifested by data balkanization, AI nationalism, lawfare, and even the potential for “splinternets.” The combination poses dangerous threats to global stability and order, and the United States could find itself on the outside looking in.

Moving toward a global agreement on how to balance open data flows with other national interests and with cybersecurity and privacy will be critical in maintaining trust in the digital world and sustaining international trade.

Yet, judged by the chaotic status of geopolitics today and the number of abandoned agreements over the last decade, existing processes are not delivering. Achieving legislative agreements internal to countries, let alone across countries, is often a very slow process that involves complex negotiations among multiple actors with competing interests, conflicting visions, and different values.

Moreover, treaties rest on an evolving body of legislation that is aggregated with time. This tendency to look back to find a solution for current or emerging problems has proven successful for most of recent history. However, old solutions are mismatched to disruptive, dynamic, and unpredictable technologies. The result is years of slow and complex negotiations that seek to find solutions to new problems through an outdated lens. Current debates pose these questions harshly. How do governments apply publisher legislation to cyber platforms? How will antitrust laws apply to tech giants?

The problem is that the digital age presents geopolitical and philosophical problems beyond the capabilities of the existing global architecture and its institutions. They remain inadequate in dealing with the cross-border, complex, and opaque nature of big data. The unhappy geopolitical context calls for an urgent Bretton Woods-style gathering to ensure that the most transformative technologies of our time do not spiral out of control and create a world order we will come to regret.

Despite receiving a great deal of attention in the media, big data is hardly touched upon in the global governance debate. Too little serious national attention is given to the interplay between big data and the ability of algorithms to generate and test hypotheses, let alone broader issues about the nature of human-machine relationships. Big data is removing old borders and constructing new ones in ways not well understood.

Additional efforts to engage innovators, thought leaders, and legislators in frank discussions that go beyond current divisions over narrow, often parochial perspectives are vital. At stake is our common future and how we would like to shape it.

The GeoTech Center champions positive paths forward that societies can pursue to ensure new technologies and data empower people, prosperity, and peace.