Putin got what he wanted at the Tehran summit. But did Iran?

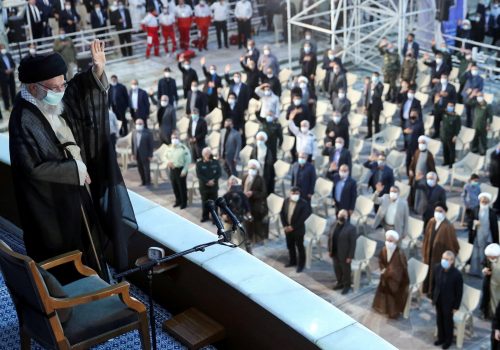

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s July 19 trip to Tehran—where he met Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, President Ebrahim Raisi, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan—was Putin’s second time outside the territory of the former Soviet Union since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The visit was for the Tehran Summit, which is within the framework of the 2017 Astana Process among Turkey, Russia, and Iran, to work toward a peaceful settlement of the Syrian crisis.

The greatest gift that Putin received at the summit was the wholehearted endorsement of his war effort in Ukraine by the Supreme Leader. Khamenei told the Russian leader, “In the case of Ukraine, had you not taken the initiative, the other side would have taken the initiative and caused the war. NATO would know no bounds if the way was open to it. And if it wasn’t stopped in Ukraine, it would start the same war sometime later using Crimea as a pretext.”

Iran, which reportedly also plans on selling Russia weapons-capable drones and providing training on how to use them, has now become fully associated with Putin’s war effort against Ukraine. This is remarkable given the historic lack of trust between Iran and Russia and the fact that Tehran has been hurt by Moscow selling its sanctioned oil at an even steeper discount than Iran has been doing, taking market share away from Iran in both China and India.

But Iran may be getting something more important out of Moscow: a guaranteed wheat supply.

Iran needs wheat, more than any other commodity. Russia is, for the moment, a source of surplus wheat, either produced domestically or stolen from Ukraine. In an environment in which international organizations warn of looming food shortages in the coming months, Iran has no choice but to look northward.

The months-long food riots in Sri Lanka that ended with the spectacular storming of the presidential palace and the ouster of the president haven’t gone unnoticed by the Islamic Republic’s leadership. In Iran, too, there have been widespread protests about the rising cost of living, as well as reports of consumers’ inability to afford even the most basic products, including everyday staples such as bread or pasta.

Government efforts to shield the poorer segments from some of the dire effects, such as subsidies, price controls, or quasi-rationing, have been unsuccessful. There are routine reports of flour shortages, of either full closure or reduced hours of bakeries, and of controlled sale of bread on a household per-head basis to buyers, which is as close to bread rationing that Iran has gotten in one hundred years.

It has, therefore, not been uncommon for analysts and pundits—initially residing abroad but increasingly from inside the country—to posit the end of the Islamic Republic caused by an internal economic meltdown. Comparisons with the demise of the Soviet Union have been all too frequent in the analyses of current events on the audio-only messaging app, Clubhouse.

Meanwhile, Russia announced that it would sell wheat only to friendly nations. By closing ranks with Putin on the Ukraine war, Khamenei is essentially trying to secure a critical economic lifeline in expectation of wheat and bread shortages that could potentially upend the regime.

Iran and Russia are also now companions in the misery of sanctions. Both countries are under the severest of economic penalties and working together to undermine the efficacy of sanctions in foreign policy could benefit both. Indeed, Russia has tried to learn from Iran’s decades-long experience with sanction busting by taking over the market for discounted oil. Reduced oil sales have been one reason—along with Iran’s apparent rejection of a deal to revive the 2015 nuclear deal—for the continued depreciation of the national currency, the rial, which passed the 320,000 rial/US dollar mark before the Tehran summit.

Should the nuclear deal finally die, Iran also wants to be on Russia’s good side so Moscow will veto any new action against Tehran by the United Nations Security Council.

Although Iran-Russia trade is relatively small, an announced decision to conduct it in rials and rubles could help reduce pressure on the rial/US dollar exchange rate. Indeed, it seems to have had at least some temporarily calming effect on the jittery forex market, which saw a downward trend toward 310,000 rial/US dollar, as well as a decline in the price of gold, immediately following the Tehran meetings.

Moscow also sought to mitigate the losses it had imposed on Iranian oil exports by announcing that Gazprom would invest $40 billion in the Iranian energy sector. Tehran is also earning transit fees by facilitating trade between Russia and India via routes that take far less time than the maritime route from St. Petersburg to India.

Iranian government officials had previously made statements that steered a more even-handed position on the war in Ukraine, calling for its peaceful resolution. The Iranians may have been reacting more to new US sanctions and threats of action against the Iranian nuclear program than any true change of heart on Ukraine. Whatever the reason, Putin had cause to be pleased with his meetings with Iranian leaders in Tehran. But it is not clear that the Iranian leadership was equally as pleased.

Mark N. Katz is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. He is also a professor of government and politics at the George Mason University Schar School of Policy and Government.

Nadereh Chamlou is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s empowerME initiative and an international development advisor.

Further reading

Tue, Jul 19, 2022

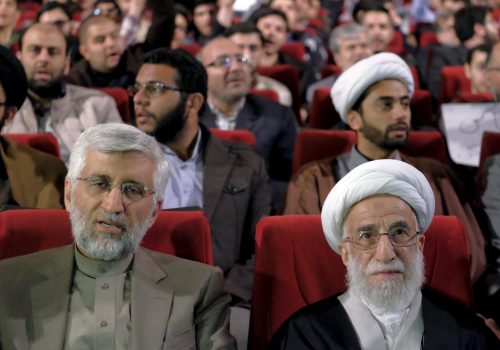

Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati may outlive all of us—even the Angel of Death

IranSource By Holly Dagres

With Ayatollah Jannati continuing his role, the Supreme Leader is solidifying his control on power and trying to ensure a like-minded successor.

Fri, Jul 8, 2022

Iran’s Supreme Leader threatened protesters. But Iranians aren’t listening.

IranSource By

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei explicitly threatened a harsh crackdown on dissidents and proposed limits on the Internet and cyberspace, harkening back to the country’s bloody suppression of dissent during the 1980s.

Thu, Jun 30, 2022

Iran’s middle class has been eroding for some time. Now it’s only getting worse.

IranSource By

With the weakening of Iran's middle class, the safety valve of the political system is eroding.

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin and Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi meet before a summit of leaders from the guarantor states of the Astana process, designed to find a peace settlement in the Syrian conflict, in Tehran, Iran July 19, 2022. President Website/WANA (West Asia News Agency)/Handout via REUTERS ATTENTION EDITORS - THIS IMAGE HAS BEEN SUPPLIED BY A THIRD PARTY.