The institutional roots of Iran’s protests

Revolutions tend to have lofty ideals, but the reality of governance often falls short of those aspirations. The 1979 Islamic Revolution was no exception. It was based on the ideals of gaining independence from foreign superpowers and achieving freedom, democracy, and justice, as well as fighting internal tyranny and supporting oppressed peoples. Forty-three years later, however, many of these goals have not been reached.

Taghi Azadarmaki, an Iranian sociologist, asserts that the Islamic Republic has become an organization suffering from many problems that cannot be solved without rational pluralist discourse. He believes that the Islamic Republic has been hostile to the middle class, which could be a culture maker and problem solver by creating civil society. Instead, according to Azadarmaki, Iran has a “quasi-middle class’’ of military generals and clerics susceptible to corruption and inefficiency.

The lack of a civil society has handicapped Iran. In developed countries, barring issues related to war and international diplomacy, many matters are dealt with by non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Iranian political scientist Mahmood Sariolghalam has written that societal progress requires socio-cultural capital: interaction, trust, cooperation, and mutual respect. Only in this way can a country achieve economic growth and freedom. The responsibility for this change lies with political elites.

In Iran, however, the government regards independent civil intermediary organizations and institutions as a fundamental danger to the Islamic order. As a result, civil society has used highly-censored Internet and social media, like Instagram and Twitter, to express demands (circumvention tools are used to bypass censorship). According to Ebrahim Fayaz, a professor of anthropology at Tehran University, such social media networks have provided a safety valve for political and other frustrations in the past.

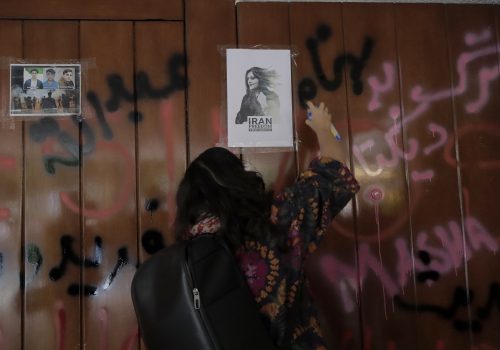

Recently, the government has further sought to choke off even this outlet by trying to limit access to the Internet through periodic, near-total shutdowns during times of unrest—as have occurred during the current protests in the wake of twenty-two-year-old Mahsa Amini’s death—as well as proposing the so-called Internet “Protection Bill,” which is secretly being implemented in recent months.

For security agencies, the presence of authoritative and influential figures in civil society is considered a danger to the system. The Islamic Republic tries to compensate by imposing “moral teachers” and “cultural personalities” of its own like the political and cultural elites, but that only deepens the alienation in this field.

In general, in Iran, an important part of the political system, especially its radical wing, does not look at civil society as part of the social system and ignores its mediating role in the development of consensus and public cohesion. The entry of political power into the public and private spheres of society and the attempt to impose uniformity have led to the elimination of healthy competition in various political, cultural, social, economic, educational, and even religious fields.

It is, in part, the lack of civil society that has caused the elite in various structures of the Islamic Republic to become a closed circle. Based on the statistical studies of Ali Saei, an Iranian sociologist, the cycle of power in Iran starts when entering government positions, and then different lobbies are used to climb the power structure. This cycle entrenches like-minded individuals in parliament, the Expediency Discernment Council, and other influential bodies.

In general, most of the political elites in the Islamic Republic are from a new oligarchy of bureaucrats in addition to military and religious elites, which have replaced the landlords and private entrepreneurs prominent before the 1979 revolution.

Even in elected institutions, the circulation of the elite is not a democratic process. In this regard, Ebrahim Fayaz calls the country’s parliament undemocratic, referring to how votes are bought in parliamentary elections and how democracy has turned into an oligarchy or aristocracy. This issue was especially noticeable in the February 2020 parliamentary election and the engineered 2021 presidential elections, which led to the victory of Ebrahim Raisi.

A true circulation of power would require reform of the way elected officials are chosen in order to permit movement from the civil society sphere to the government sphere and vice-versa. The development of social groups and networks are crucial for the renewal of elites and investing in the development of social networks, such as associations of writers and artists, as well as NGOs and political parties. This incentivizes ordinary citizens to participate in democratic processes and to feel more of a stake in the decisions their government makes.

In Iran, however, competing discourses are limited. Social bodies belonging to these discourses have no authorized channel to express their demands, which pushes many to protest into the streets.

This uniformization of views began after the 1979 Revolution with the creation of various structures and organizations, including supposedly “rival” political factions. There was a struggle between more revolutionary and traditional forces and more modern and liberal groups, as evidenced by the short-lived administration of post-revolutionary Iran’s first prime minister, Mehdi Bazargan. Traditional religious organizations, such as the Combatant Clergy Association, the Society of Seminary Teachers of Qom, and the Islamic Republican Party, opposed the more modern parties like the National Front, the Freedom Movement, and the Islamist Socialist political party. While the modern movements did not believe in integrating religion and the state, the traditional anti-modern forces managed to mobilize the masses and use nominally democratic institutions to emerge as dominant.

In the cultural and educational field, this uniformization intensified with a ‘‘Cultural Revolution’’ that led to the closure of universities from 1980–1983 and the dismissal of many university professors.

According to this ‘‘Cultural Revolution,’’ Iran’s educational system should be designed according to revolutionary and Islamic norms. The Islamization of universities and the Islamization of the humanities curtailed the emergence of competing discourses in the humanities and social sciences.

Those in power emphasized so-called Islamic humanities to purge Western approaches to liberal arts and sciences, hindering critical and free-thinking in universities, which is partly why students are taking part in the protests.

The Islamic Republic has alienated many Iranians and, without a thriving civil society, is contributing to the rising rhythm of protests within Iran.

Javad Heiran-Nia is director of the Persian Gulf Studies Group at the Center for Scientific Research and Middle East Strategic Studies in Iran. Follow him on Twitter: @J_Heirannia.

Further reading

Fri, Sep 30, 2022

The protests in Iran have an anthem. It’s a love letter to Iran.

IranSource By

Shervin Hajipour's “For the sake of” has captivated the whole nation.

Fri, Sep 30, 2022

Iran is having nationwide protests. Is it a ‘revolution’?

IranSource By Sina Azodi

Despite the widespread protests and international support, one has to be cautious in predicting the outcome.

Wed, Sep 28, 2022

I’m a member of Gen Z from Tehran. World, please be the voice of the people of Iran.

IranSource By

To all the brave and beautiful people out there who know what freedom feels like, be our voice.

Image: A police motorcycle burns during a protest over the death of Mahsa Amini, a woman who died after being arrested by the Islamic republic's "morality police", in Tehran, Iran September 19, 2022. WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS//File Photo