The Supreme Leader doesn’t want détente with the United States—ever

Iran’s Supreme Leader has cemented no talks and no relations with the United States as the grand strategy guiding Tehran’s foreign policy. He offers some arguments behind this strategic thinking and they are all flawed.

On August 14, 2018, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei argued that “we can enter the dangerous game of talking to the US only when we reach the. . . economic power that we have in mind so that we are not influenced by America’s brinkmanship and pressure.”

In the last hundred years, no country that has been in constant conflict with the US has been able to achieve sustainable growth. China and Vietnam, whose systems are in clear contrast with the United States—especially the latter, which was in a bloody twenty-year war with the US—have learned this lesson. That is, in part, why America is now Beijing and Hanoi’s leading trade partner.

This argument is even flawed when you look at Iran’s own experience since the seizure of the American embassy in Tehran in 1979. Its unwavering hostile position toward the US being a major factor, the Islamic Republic has experienced unceasing devaluation of its national currency, rampant inflation, and stress on its economy as a result of punitive sanctions over the decades. Iran has also been unable to establish an enduring commercial and technological relationship with any other economic power because of its tense relationship with the US—again, because of sanctions.

Some may argue that President Donald Trump’s move to abandon the 2015 nuclear deal with Tehran and reimpose sanctions is the reason Iran or, rather, Khamenei continues this hostile position toward America. Proponents of this argument forget that, in 2015, 42 senators and 162 members of the House, along with President Barack Obama, stood behind the nuclear agreement with Iran and fought tooth and nail with Iran hawks and lobby groups. When Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif was photographed walking across a Geneva bridge with his American counterpart John Kerry, many concluded that overt hostility between Iran and the US was over. Many believed that talking between the two countries would become the new normal and that moderates would gain the upper hand in Iran.

In an interview in 2015, President Obama said, “It’s also possible that if we can successfully address the nuclear question and Iran begins to receive relief from some nuclear sanctions, it could lead to more investments in the Iranian economy and more opportunity for the Iranian people, which could strengthen the hands of more moderate leaders in Iran.”

About the same time, Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, said, “It is possible to change hostility with the US to friendship. . . Reopening of the US embassy in Tehran is not impossible.”

Both Obama and Rouhani were wrong.

Shortly after inking the deal in 2015, Ayatollah Khamenei banned further talks with the United States, closing the door on any possible improvement in US-Iran relations and disappointing supporters of détente in both countries. “We agreed to hold talks with America only on the nuclear issue and for particular reasons,” he remarked. “I have not authorized negotiations and [we] will not hold talks with them.” The Supreme Leader, then, added, “The Iranian nation expelled this Satan [from the country]; we must not allow that when we expelled it through the door, it could return and gain influence [again] through the window.”

Khamenei and his followers, who dominate the system, are concerned that “negotiations with the United States would open gates to their economic, cultural, [and] political influence” and ultimately erode the system’s Islamic character.

Khamenei, also, maintains that “resistance [against US hegemony] is costly, but [that] the cost of capitulation is significantly greater.” He argues that Iran will lose its independence if it restores relations with the US. The problem with this position is that Khamenei equates having relations with the US to capitulation and loss of sovereignty. If we accept his reasoning, the only independent countries are the handful that have hostile relations with the US—the rest are, apparently, American serfs.

Not everybody in the Iranian leadership accepts Khamenei’s rationale, however. A glaring example is Foreign Minister Zarif. The moderate faction has consistently maintained that ending hostilities and interaction with the US is not only possible but in the interest of the nation. Nevertheless, the hardline faction led by Khamenei has, on all occasions, torpedoed US-Iran rapprochement and labeled those who support direct talks with the US as being “stupid” and “traitor[s]”. By quitting the Iran deal in May 2018, Trump has further provided the Supreme Leader and his supporters with a powerful means to justify their anti-Americanism.

But, the bigger problem with Khamenei’s argument is whether the Iranian people support this policy, given the constant pressure that Iran has been under for the last 41 years as a result of enmity with the US. There is no way to conduct a poll in Iran to ask about Khamenei and the system’s popularity. But the recent parliamentary elections may be able to give us an idea.

Based on the official figures, which we will assume are not manipulated for the sake of argument, the turnout in the February 21 elections was about 42 percent. This has been the lowest turnout in any election in the Islamic Republic’s history. In Tehran, the capital, turnout went down from 50 percent to 26 percent.

Here is the interesting part: one presumes that all the supporters of Ayatollah Khamenei turned out to vote. Why? Because Khamenei made a statement that participation in the election “is not just a national and revolutionary duty,” it is “a religious duty.” This is a fatwa. So, here is the interpretation of the above figures. Out of roughly 58 million eligible voters, about 34 million turned their backs on Khamenei’s fatwa despite emphasizing that voting is a religious duty.

It could be argued that, even in developed countries, the turnout for national elections is historically low. In the US, for example, the turnout in the 2010 and 2014 midterm congressional elections were 45.5 and 41.9 percent, respectively. But the significance of low turnout in Iran is that tens of millions and, in this case, the overwhelming majority, ignored the Leader’s fatwa. It’s worth noting that despite Khamenei’s injunctions, Iranian society—particularly in the urban areas, where 70 percent of the population lives—is already profoundly “Westoxified” judging from the social behavior and entertainment choices of the young and the middle and upper classes.

In other words, they do not accept Khamenei and his policies. On March 21, on the occasion of Nowruz, the Iranian New Year, the Supreme Leader said in a speech, “No nation succeeds if it seeks hedonism. . . production of goods should increase by our working ten-fold.” Why should the Iranian people work eighty hours a day instead of eight? Seemingly, to compensate for shortages resulting from strategic opposition to the US.

But, will this hostile position toward Iran end after the death of the 81-year-old Khamenei, who is rumored to have cancer? So far, Ebrahim Raisi, the head of Judiciary, has the strongest chance to assume the leadership position after Khamenei’s demise. In any event, after Khamenei’s era ends, Iran will still be ruled by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) regardless of who comes to power. And the IRGC’s central doctrine is that the hostility between the Islamic Republic and the US is unresolvable and eternal. Even Khamenei is careful not to cross this IRGC red line.

Shahir Shahidsaless is an Iranian-Canadian political analyst and freelance journalist. He is the co-author of Iran and the United States: An Insider’s View on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace. He is a contributor to several websites with focus on the Middle East as well as the Huffington Post. He also regularly writes for BBC Persian. Follow him on Twitter: @SShahidsaless.

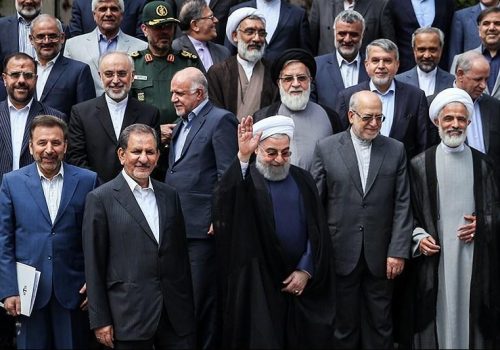

Image: Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei shows him on stage during a meeting with Iranian air force commanders in Tehran, Iran, on February 08, 2020 (Reuters)