The shock wave from the unprecedented assassination by the United States of Iran’s most powerful military commander has reverberated across the Middle East, leaving the region bracing for an expected retaliation and potential escalation of violence between Tehran and Washington, and their allies and proxies.

The United States justified the assassination of Major General Qasem Soleimani, the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) Quds Force, as a preemptive strike designed to thwart a series of planned attacks against US citizens and interests in Iraq and possibly elsewhere. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that the “decision to remove Soleimani from the battlefield saved American lives.” The Iraqi general, once dubbed in the West as the “Shadow Commander,” was killed when a drone fired at least one missile into his vehicle soon after he departed Baghdad International Airport.

His death brings to mind memories of an earlier aerial assassination in south Lebanon during February 1992. The aftermath of that deadly attack twenty-eight years ago may provide pointers for what might unfold in the wake of Soleimani’s violent death—and possibly remind us of the risk of unintended consequences.

Sheikh Abbas Musawi, the then secretary-general of Lebanon’s Iran-backed Hezbollah organization, was returning to Beirut on February 16, 1992 having attended a ceremony in Jibsheet village marking the eighth anniversary of the assassination of one of Hezbollah’s founders. Musawi was travelling in a black Mercedes with his wife and five-year-old son, accompanied by two Range Rovers filled with armed bodyguards. Tailing the convoy was a pair of Israeli Apache AH64 helicopters which, a few miles from Jibsheet, unleased missiles into the motorcade, killing the Hezbollah leader along with his wife and son and five of the bodyguards.

It was the most significant assassination carried out against a Hezbollah official since the organization began to emerge following Israel’s invasion and occupation of southern Lebanon a decade earlier. Musawi was a revered figure among Hezbollah’s cadres and his death was a blow to the organization’s morale. It appeared that Israel had scored a major achievement in dispatching its Lebanese enemy.

A month after Musawi’s assassination, however, a vehicle-borne suicide bomber attacked the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires, killing twenty-nine people and wounding more than 200. Hezbollah officially denied responsibility for the bombing, but the message was clear: Hezbollah had the capability to attack Israeli interests around the world. The message was apparently understood in Israel; although Israel continued to assassinate Hezbollah military commanders when it could find them, it avoided killing senior members of the leadership cadre for the next sixteen years.

Musawi’s assassination also spurred Hezbollah to fire rockets into northern Israel for the first time, effectively bringing populated areas of western and northern Galilee into the battlespace alongside the Israeli army then occupying south Lebanon. Hezbollah would continue launching rockets into Israel over the following years as a tit-for-tat retaliation for Lebanese civilian deaths at the hands of the Israeli military.

The third significant outcome was the election a day after Musawi’s death of his protégé, Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah, then only thirty-two years old. The cogs of Hezbollah’s machine continued to turn despite the death of the venerated Musawi. Indeed, Nasrallah’s ascendancy to the leadership of Hezbollah marked the beginning of the organization’s long march from a hit-and-run, guerrilla-style force that drove the Israelis out of Lebanon in 2000, successfully stood its ground against the Israeli military in the month-long war of 2006, and into today an army of tens of thousands of battle-hardened fighters armed with ballistic missiles that can strike specific buildings pretty much anywhere in Israel. Small wonder, perhaps, that Israel classifies Hezbollah as its number one threat.

A similar reaction occurred just two years later in July 1994 when a suicide bomber blew up a van loaded with more than 600 pounds of explosive beside AMIA Jewish charity building in Buenos Aires, killing eighty-five people and wounding another 300. Again, Hezbollah denied responsibility. But the attack came six weeks after an unprecedented Israeli airstrike against a Hezbollah training camp in Lebanon’s eastern Bekaa Valley that left more than forty recruits dead. A Hezbollah official said in the aftermath of the raid that “we are preparing an operation that will surprise the world.”

It remains to be seen what effect Soleimani’s assassination will have on the Quds Force and its ability to command and control the operations of its many Shia proxies scattered across the Middle East. But, like Hezbollah, the Quds Force operates as a coordinated institution that is larger than any one figure, even someone of the caliber of Soleimani. Major General Esmail Qaani, who replaced the slain Quds Force leader, was Soleimani’s deputy since the late 1990s, suggesting that even if he lacks his predecessor’s charisma, he has the experience to continue the mission.

As for the manner of retaliation, Iran’s options span the globe. After all, in 1992, the then relatively small Hezbollah was able to exact vengeance against Israel for Musawi’s death in South America, far from the Middle East. On the other hand, Soleimani’s death comes as Iran faces an array of strategic challenges. Protest movements in Iraq and Lebanon seek to overturn the corrupt and incompetent political classes which could threaten Iran’s influence in both countries. Iran’s military presence in Syria is routinely targeted by Israel and faces an increasingly rivalry with Russia, the other main external stakeholder in the war-ravaged country. At home, Iran faces crippling US sanctions which has helped decimate the economy and send prices soaring.

Senior officials in Washington are signaling that if Iran targets US personnel or interests, the response will be disproportionate to the act to hammer home the futility of taking on the world’s most powerful military machine. Statements emerging from Tehran and Beirut on January 6, however, suggest that Iran may not be seeking a one-off spectacular but could resort to its multi-national network of proxy forces to mount a low-level asymmetric campaign against US military interests across the Middle East.

“The response, for sure, will be military and against military sites,” Hossein Dehghan, the military advisor to Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, told CNN.

In Beirut, Nasrallah said in a speech that the “axis of resistance”—meaning Iran, Syria, and its substate allies—has a responsibility to retaliate.

“The fair punishment is the removal of the US military presence in the region,” he said.

But the Iranians also must factor into their calculations that the incumbent of the White House is wholly unpredictable. US President Donald J. Trump appears to be writing new rules of the game by killing Soleimani. Turning the other cheek is not in the Islamic Republic’s DNA, but, given the stakes, finding a response that will satisfy honor and maintain a degree of deterrence against further US actions represents a significant—and potentially very dangerous—challenge.

Nicholas Blanford is a nonresident senior fellow with the Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Further reading

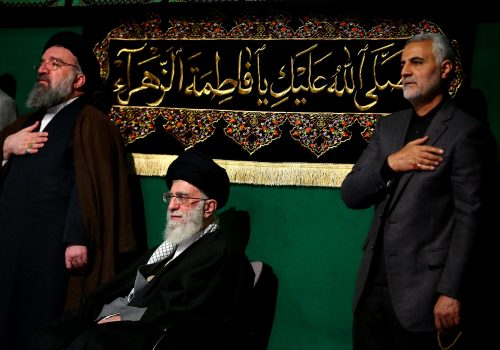

Image: Lebanon's Hezbollah supporters chant slogans during a funeral ceremony rally to mourn Qassem Soleimani, head of the elite Quds Force, who was killed in an air strike at Baghdad airport, in Beirut's suburbs, Lebanon, January 5, 2020. REUTERS/Aziz Taher