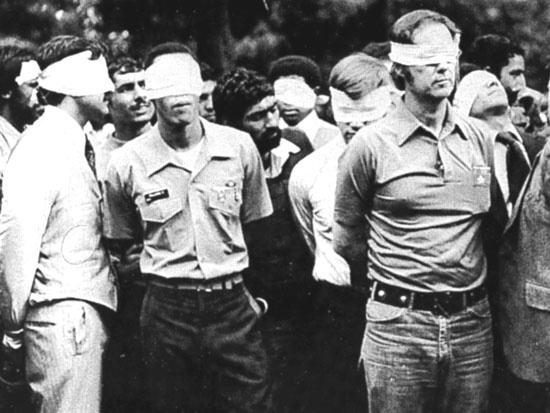

On November 4, the Islamic Republic will again “celebrate” the taking of the US Embassy forty years ago. Regime loyalists will chant “Death to America” and the spectacle will be broadcast around the world, no doubt prompting statements of outrage from the US and other governments.

The poisons spread by the events in Tehran four decades ago have yet to dissipate. Indeed, they are still toxic and still in the system. Just ask Baquer and Siamak Namazi, Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, Xiyue Wang, and others whom the authorities in Tehran in their wisdom have imprisoned for years for no apparent reason, except, in the case of Princeton University historian Wang, for “spying” on the long dead.

In forty years the Islamic Republic has learned nothing. It has compounded its original mistakes and continued on the destructive path of hostage-taking that it first lurched into in the aftermath of a violent revolution. That path, a textbook case of unskilled diplomacy, wreaked havoc on both the nation and millions of individual Iranians.

The record is clear, if depressing. Forty years ago, those in charge of the Islamic Republic made bad decisions, and Iranians—never consulted on the matter—paid the price. They became victims of their leaders’ mistakes. The outcomes were war, international isolation, dictatorship, violence, a damaged economy, and a flight of educated and skilled people. Iranians found themselves with a worthless currency, a passport welcomed almost nowhere, and thousands of widowed, orphaned, and maimed war victims.

In September 1980, when Saddam Hussein’s Iraq—the clear aggressor—attacked Iran, the Iranians found, thanks to their own diplomatic malpractice, almost no foreign support or sympathy. Those events touched me personally as one of the more than fifty American hostages held for 444 days. I must admit that when, from inside the Komiteh prison, I first heard, Iraqi aircraft attacking Tehran my reaction was, “Well, they’re getting what’s coming to them.”

Almost no one stood up for a victimized Iran. A few years later, the US and most of the international community remained silent when Saddam used poison gas against both Iranians and his own Kurdish people. Even those atrocities brought Iranians no sympathy.

The hostage-taking of 1979-1981 was an unmitigated disaster for Iran and its people.

After forty years, the evidence should be clear to even the most benighted. The hostage-taking of 1979-1981 was an unmitigated disaster for Iran and its people. What remains remarkable, however, is that after so long, the leaders of the Islamic Republic continue to delude themselves and their citizens and have not publicly recognized the reality of that disaster. They will not admit they screwed up. The closest they have come was in 1998, when Mohammad Khatami, newly elected president on a platform of outreach to the West, told CNN’s Christiane Amanpour that he “regretted” the injury to Americans’ feelings caused by Iran’s holding of fifty-two American diplomats. Ironically, Khatami is now also a hostage of sorts—stripped of his passport and banned from appearing in Iranian media.

In 2016, when Americans were debating the pros and cons of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) between Iran and five world powers plus Germany, some opponents criticized not the contents of the agreement, but the Islamic Republic’s record of taking foreigners and dual-nationals as hostages. How, they asked, can we trust people who do something like THAT?

The Islamic Republic has never come to terms with what happened during the Iran Hostage Crisis. In 2011, while visiting the United Nations General Assembly, then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad spoke about the need to eliminate the persisting “negative mentality” between Americans and Iranians. When I suggested to him that one way of doing so was not to appoint former embassy hostage-takers to positions in his cabinet, Ahmadinejad looked bewildered as though he did not see the connection. As some members of his entourage tried to hide their grins, Ahmadinejad replied, “Well, we treated you nicely then, didn’t we?”

To be fair, the Islamic Republic is not alone in refusing to confront a shameful past. It took the American government sixty years to acknowledge its role in—and the negative effects of—the CIA-backed coup that overthrew Iran’s nationalist Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953. It took over fifty years before an American president—Barack Obama in June 2009—could say, “the United States played a role in the overthrow of a democratically elected Iranian government.” It took sixty-five years for the US government to release the official records from that period. Not much reason to be proud.

Why has the Islamic Republic persisted in a policy that has been shameful and destructive for forty years? There may be short-term financial gains or concessions in prisoner swaps, such as the one that occurred with the US upon implementation of the JCPOA in 2016. But those are less important than the ongoing debate within Iran over the country’s political direction.

Those in power continue to insist that, despite all evidence to the contrary, the 1979 hostage-taking was a splendid victory. For some, like Ahmadinejad, those events are unrelated to the present and occurred “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.” The government still sponsors events commemorating the day, with marches, speeches and slogans proclaiming its glory. Many of Iran’s current leaders benefitted from those events, using them to crush rivals, install a dictatorship, and solidify power.

The Islamic Republic is now caught in a trap of its own making. Those at the top are invested in a losing hand, and must keep repeating the same obviously false narrative. If taking hostages was good then, it has to be good now. For the regime to give up on an obviously destructive policy would force it implicitly to admit its opponents were right and that forty years ago it made a mistake that brought incalculable damage to Iran and Iranians. Rather than make such an admission, it compounds the mistake by repeating it.

John Limbert is a retired professor of Middle Eastern Studies at the United States Naval Academy in Maryland. A Foreign Service Officer for thirty-four years, he served as deputy secretary of state for Iran under the Obama administration. He was among the fifty-two Americans held hostage during the 444-day Iran hostage crisis. He is the author of Iran: At War with History, Negotiating with Iran: Wrestling the Ghosts of History, and Shiraz in the Age of Hafez.

Image: Blindfolded US hostages and their Iranian captors outside the US embassy in Tehran (Reuters)