Will Russia be able to keep its bases in Syria?

Russia was using its air base in Syria to attack the Assad regime’s opponents in Syria right up until early December. But now that the Assad regime, which Moscow had long supported, has been overthrown and its Islamist opponents are triumphant, Russia has made known that it would like to keep its naval and air bases in Syria.

It is not yet clear whether Russia will be able to. According to Reuters, Russia has moved its naval vessels out to sea from the Tartus naval base and drawn down equipment from its Khmeimim air base but still intends to keep both. According to an unnamed Syrian rebel official quoted in Reuters, though, the new Syrian government has not made a final decision. Rather, he said that, “It is a matter for future talks and the Syrian people will have the final say.” In other words, it is not yet clear what will happen.

It is understandable that Russia would want to keep these bases. The Russian airbase in Syria reportedly plays an important role in supporting Moscow’s “Africa Corps” (the reformulated Wagner Group) in several African countries. The naval base helps Russia maintain its presence in the Mediterranean Sea. Russia cannot access the Mediterranean as easily from the Black Sea due to Turkish restrictions on the passage of warships between the two seas, which Ankara imposed after Moscow’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Finally, Russia’s loss of these bases would simply be humiliating for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

But why would the new Syrian government—led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and other Turkish-backed groups—be willing to let Russia keep these bases?

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

Some argue that they may be willing to do so in exchange for Russian recognition of the new post-Assad Syrian government. With Western countries hesitant to recognize a government led by HTS due to its former association with al-Qaeda, HTS might just be willing to let Russia keep the bases in exchange for diplomatic recognition.

But this assumes that HTS is desperate for Russian recognition. It might not be. Indeed, the Russian decision to grant asylum to ousted former Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad might make it difficult for HTS to normalize relations with Moscow at all, much less allow it to retain the two bases. Indeed, HTS might not just be unwilling but unable to make any deal with Russia unless Moscow were to extradite Assad for trial in Syria—something Putin is highly unlikely to do.

Another factor is whether HTS can countenance how Moscow uses its bases. Africa Corps (and Wagner before it) were invited by African governments to displace the French military presence in the Central African Republic, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso (and in the case of Niger, to also replace the US military presence there). Russian forces are helping these African governments fight against Islamist opposition groups as French and US forces were doing previously, though Russia’s efforts in this regard have been brutal and not very effective. There are, of course, rifts between Islamist opposition groups, including between HTS on the one hand and both al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) on the other. But since the Islamist groups in Africa pose no threat to HTS, it is not clear why HTS would support Russian military action against them via bases in Syria.

But it is also possible that other external actors could drive HTS and Russia closer together. Israeli forces have launched hundreds of attacks on caches of weapons in Syria after the downfall of Assad—not because HTS has moved to attack Israel with them, but to prevent their potential use by HTS and others in Syria against Israel. While Israel’s motivation may be understandable, the continuation of these attacks could have the unintended consequence of making HTS willing to let Russia retain its bases in exchange for protection against Israel.

Further, just like the Assad regime, the Turkish-backed Syrian forces that ousted him will likely want to gain control over the territory in northeastern Syria that US-backed Kurdish forces now rule. If the United States helps the Kurds resist, HTS could be persuaded to allow the Russians to keep the bases in exchange for Russian support against both Kurdish and US forces.

HTS, of course, may prefer to see all non-Muslim forces—US and Russian alike—leave Syria, and rely instead mainly on Turkey, its main backer against the Assad regime.

There are, then, plausible reasons why the new Syrian government might want to expel the Russians or allow them to stay. Their decision, though, is likely to be made on the basis of how the new government views the behavior of other governments toward it.

It would be in the United States’ and Israel’s interests not to give the new Syrian government reasons to let Russia keep those bases.

Mark N. Katz is a professor emeritus at the George Mason University Schar School of Policy and Government, and a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Further reading

Thu, Dec 5, 2024

What does Turkey gain from the rebel offensive in Syria?

MENASource By Ömer Özkizilcik

The rebel offensive took many by surprise, but analysts familiar with the situation in Syria were aware that the rebels were prepared to launch it by mid-October.

Tue, Dec 10, 2024

Where Syria goes next after the fall of Assad

MENASource By Frederic C. Hof

With the Assad family agone, Syria, at long last, has a chance to achieve the kind of political transition envisioned by the 2012 Geneva Final Communique and UNSCR 2254.

Tue, Dec 17, 2024

Dispatch from Damascus: Celebrations and concerns as a new Syria takes shape

New Atlanticist By Ömer Özkizilcik

Syrians in Damascus are celebrating the fall of the Assad regime, but that joy is mixed with concern for how the country’s new leaders will govern.

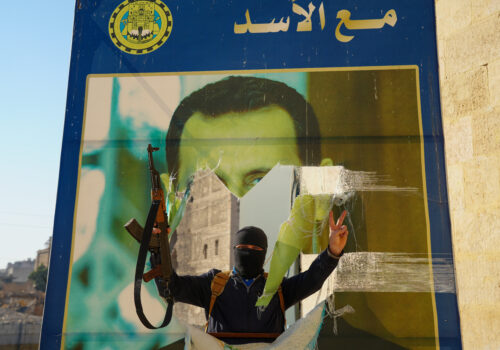

Image: A Russian military vehicle heads towards Hmeimim air base in Syria's coastal Latakia, Syria, December 15, 2024. REUTERS/Umit Bektas