Mr. Wang goes to the Middle East

On March 30, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi wrapped up a week-long trip to the Middle East that saw him visit six countries: Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Oman, and Bahrain. It comes on the heels of a three-country visit—to Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and Doha—by Russia Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov earlier in the month. Taken together, there is a perception that the Joe Biden administration’s tepid engagement with its Middle East and North Africa (MENA) partners is creating opportunities for external powers. In China’s case, it makes more sense to look at the trip as a message to Washington rather than an intention of Beijing’s greater ambitions for the Middle East.

China has been having problems with several Western democracies in recent years, but the Donald Trump administration’s focus on the trade war gave Beijing a free pass on human rights issues in Xinjiang province and Hong Kong while damaging United States allies’ and partners’ ability to push back. The Biden administration’s emphasis on values in its foreign policy has specifically targeted China, among other countries. With sanctions and condemnation coming from the US, European Union, United Kingdom, and Canada, it makes sense that China would choose now to reach out to other countries that are also concerned with the direction of US foreign policy under President Biden—and the Middle East is home to many such countries.

So, what happened on the trip? For all the press coverage, there was surprisingly little in the way of new developments. Wang’s first stop was a meeting with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) in Neom, where he offered a vague invitation to Israeli and Palestinian “public figures” for peace talks. That the offer was made on election day in Israel, when Israelis were otherwise engaged, meant that it was largely met with indifference. China has made this offer before, most recently in 2017, and it is clear that nobody sees Beijing as an especially useful mediator on an issue where it has had little history or impact. It was most likely an attempt to drum up a positive response from the Arab public. China has long seen itself as a leader of the global south and in this regard has always offered symbolic support to the Palestinians. In this case, it seemed like a low-cost opportunity to distinguish China from the US, especially given the anger of many Arabs who believe that Palestine was marginalized even more during the Trump years.

Another announcement during the Saudi visit was a five-point plan for Middle East security, calling on countries in the region to respect each other, uphold equity and justice, achieve nuclear non-proliferation, jointly foster collective security, and accelerate development cooperation. This was boilerplate stuff and had little that was especially new, although it is a clear sign that Beijing will continue to tread lightly on security matters.

Wang’s time in Turkey provided a significant contrast on the issue of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Chinese state media reported that MBS expressed support for China’s Xinjiang policy and that both pledged the two countries would continue to practice non-interference in each other’s domestic affairs. However, in Istanbul, protesters gathered, waving East Turkistan (Xinjiang) flags and chanting, “Stop Uyghur genocide, close the camps.” Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said he conveyed Turkey’s “sensitivity and thoughts” about the Uyghur issue. Other than Israel, there are no other countries in the Middle East where Xinjiang receives even this relatively modest level of scrutiny, and it remains a wedge issue between China and Turkey.

Not surprisingly, Wang’s stop in Iran provided the banner headline: the long-rumored twenty-five-year China-Iran deal was finally signed. This has been in the works since January 2016, providing a good indication of the relatively low priority level it has held for Beijing. Many read this as a sign of Chinese support for an aggressive Iran. Though, as I’ve written here before, China’s deep commercial interests in the Middle East are with US allies and partners—all of which consider Iran their greatest threat. China is not going to throw away billions of dollars’ worth of contracts and investments as well as years of diplomatic capital for the privilege of a closer relationship with an isolated and revisionist middle power that has no valuable regional partnerships.

So why sign the deal? As always, it is more useful to look at the China-Iran agreement in the context of China’s relationship with the US. During the Alaska summit, both the Chinese and American delegations described Iran as an issue where they could work together. At the same time, Chinese leaders needed to show their constituents that they were willing and able to stand up to the US. Former Chinese ambassador to Iran Hua Liming described the agreement as a “momentous change,” claiming that Beijing had long avoided getting too close to Iran because of US “sensitivities,” but “with fundamental changes in China-US relations in recent months, that era has gone.” However, the fundamental fact remains that time and again China has prioritized relations with Washington over Tehran and, despite the currently rocky relations, this is not going to change. Beijing has leverage in Iran and China wants better relations with the US. Rather than providing a lifeline for the Islamic Republic, China is most likely building its value as a bargaining chip.

The Iran partnerships also must be understood as a framework for cooperation rather than a set of commitments. When asked about the agreement during his press briefing, Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian described it as a plan “charting course for long-term cooperation. It neither includes any quantitative, specific contracts and goals nor targets any third party.” Any details, like $400 billion worth of investment or Chinese bases on Iranian islands, should be treated with skepticism.

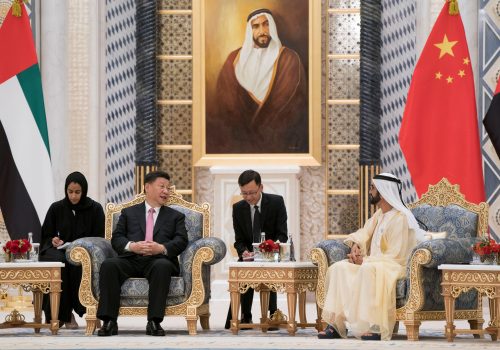

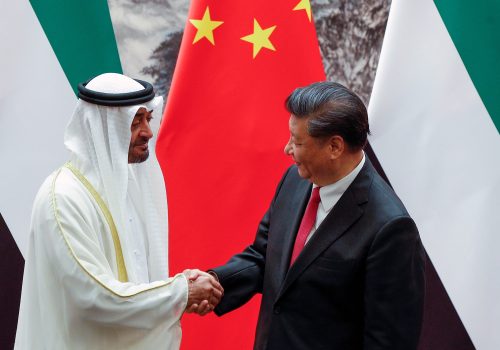

Far less publicized but with more tangible outcomes, Wang’s visit to the UAE showed what an implemented comprehensive strategic partnership looks like. China’s Sinopharm China National Biotech Group and the UAE’s G42 announced a joint venture that aims to produce up to two hundred million doses of the Sinopharm vaccine in the UAE. It is a clear indication of trust between the two countries and a marked contrast with Iran. Five years into the Sino-Iranian partnership, they are still trying to lay the foundation. Three years into the China-UAE partnership, there is a depth and breadth of engagement that reinforces a point that bears repeating: China’s MENA interests are met by working with stable, networked, status quo countries, which is why UAE is the MENA country that has the most well-rounded relationship with China.

The trip wrapped up with visits to Oman and Bahrain, where there were few big announcements. In Muscat, the Chinese foreign minister emphasized Beijing’s desire to complete the long-negotiated China-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) free trade agreement, a task that is more likely now that Qatar is coming back into the fold of the GCC. In Bahrain, talk was mostly focused on the coronavirus, but China’s tech conglomerate Tencent announced its cloud division will open a data center in Manama in March, so that bears watching.

In all, it was a big trip that underscored the range of existing Chinese interests in MENA but did not fundamentally change much in the region. It also should be noted that, with State Councilor Yang Jiechi’s recent trip to Qatar and Kuwait, this marks the first time that every GCC country has received a senior Chinese official in the same calendar year. China’s MENA footprint is only getting deeper.

Jonathan Fulton is a senior nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council and an assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi. Follow him on Twitter: @jonathandfulton.

Image: Iran's Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi bump elbows during the signing ceremony of a 25-year cooperation agreement, in Tehran, Iran March 27, 2021. Majid Asgaripour/WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS ATTENTION EDITORS - THIS IMAGE HAS BEEN SUPPLIED BY A THIRD PARTY.