Russian aid in Syria: An underestimated instrument of soft power

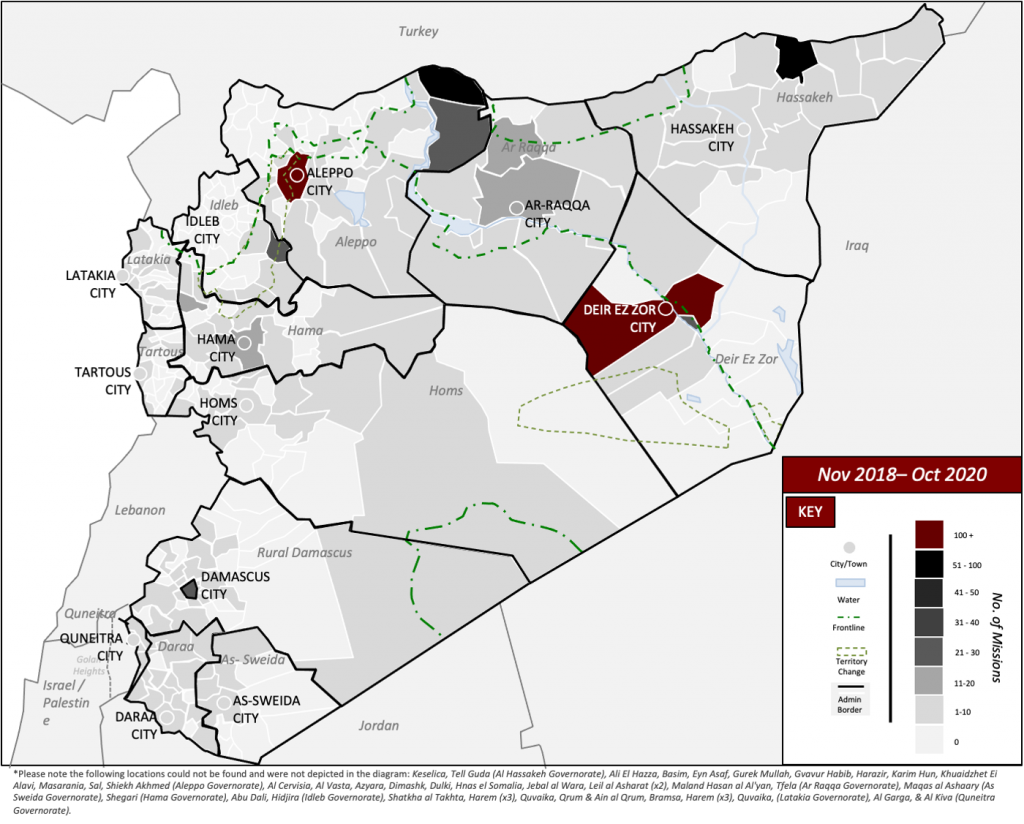

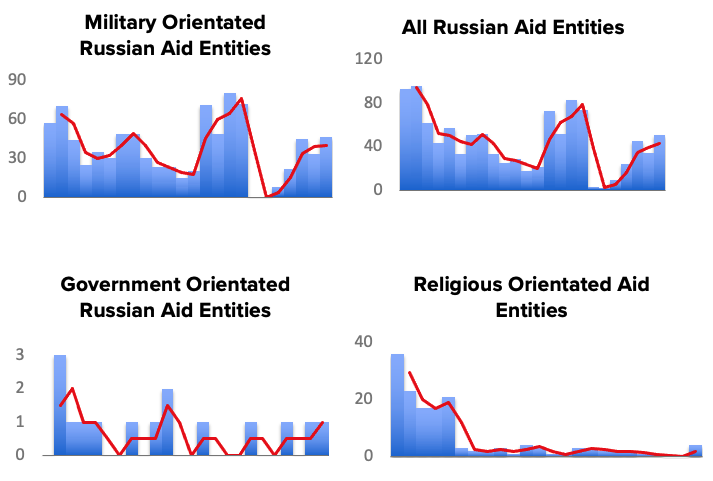

Previous research on Russia’s shallow and symbolic use of humanitarian aid in Syria has often focused on Russia’s Center for Reconciliation and Conflicting Sides (CRCS). Less explored are the twenty-five other Russian entities that have reported delivering aid in the country at one point or another since Russia intervened in the Syrian conflict in late 2015 (Figure 1 and 2). By forming a shadow aid system in the country, this seemingly innocuous ecosystem poses an underestimated threat to the humanitarian community and the Syrian people. Free from needing outside help by the international community or United Nations (UN), Russia’s self-sufficient aid ecosystem undermines, devalues, and rivals UN-led efforts in Syria, threatens to erode trust in the wider aid system, and provides a dangerous alternative narrative about the humanitarian environment in Syria for the Bashar al-Assad regime.

An often-overlooked instrument of Russia’s soft power, Russian aid efforts in Syria diversify Russia’s political and military efforts in Syria as well as amplify their foreign policy goals in the region. However, by recognizing the nuances of Russia’s problematic humanitarian engagement in Syria, opportunities to counter this threat emerge.

Viewing Russia’s aid efforts through their own eyes

This study is based on data from publicly available information from the Russian entities identified in this report. While this limits the findings of this study, such as potentially missing unreported actions or the data being skewed towards how each entity wants to craft its public image, the data is still helpful, as it provides a snapshot into how Russia wants the world to view its aid efforts in Syria.

Russia has long viewed the provision of aid as a foreign policy instrument to repair its image as a credible and dominant power after the fall of the Soviet Union. As far back as 2007, official policy stated that aid was used to “strengthen the credibility of Russia and promote an unbiased attitude of the Russian Federation in the international community.” Russian policy experts have updated this position in relation to Syria, highlighting that Russian humanitarian activity in Syria aims to improve Russia’s image in the Middle East.

While other countries also promote their narratives through the provision of aid, there is typically a degree of separation between the state and humanitarian efforts. For example, the United States uses the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to fund and support numerous UN agencies and humanitarian non-governmental organizations (NGOs) around the world. In turn, these entities are accountable to their own boards, monitoring procedures, and other government donors (if they receive funding elsewhere), diluting US soft power in aid.

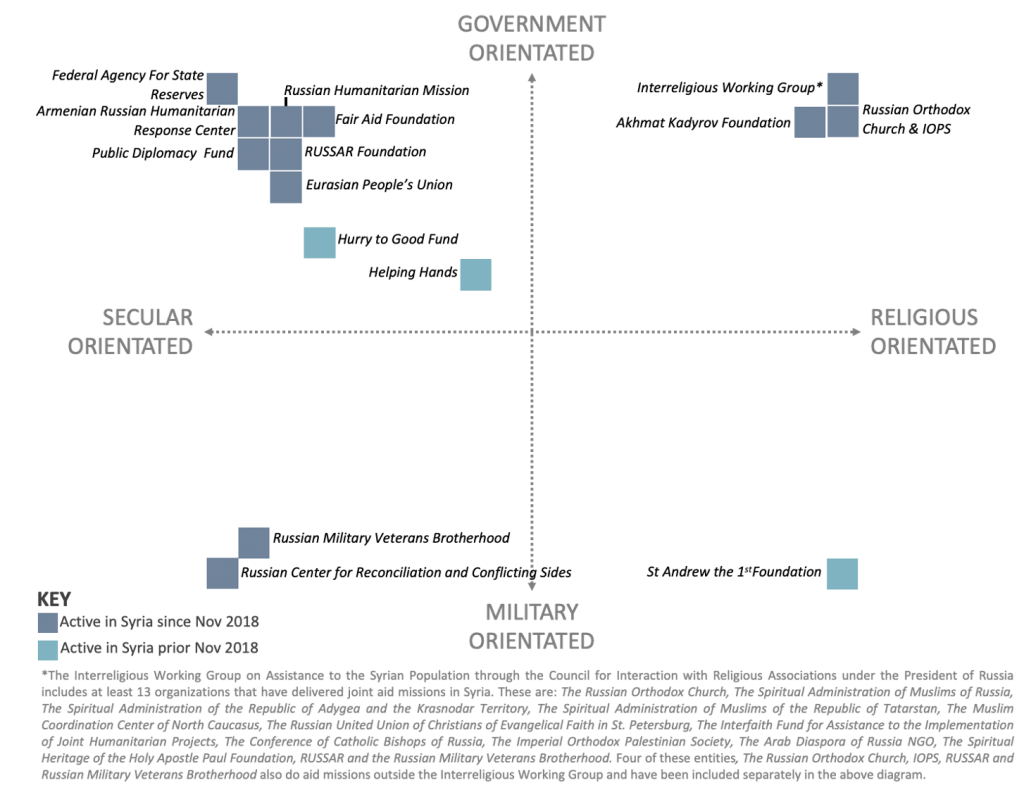

In contrast, Russia does not have a USAID or the equivalent and has not signed up to the Good Humanitarian Donorship (GHD) principles, which also tempers soft power in humanitarian action. Instead, Russian aid in Syria uses numerous entities that have strong links to the state or funding from it. The Defense Ministry’s CRCS and The Federal Agency for State Reserves are clearly state-linked, but many other organizations are accountable to the state through senior leaders within Russian aid organizations. These individuals are typically active Kremlin-supporting politicians or are connected to the President’s Office as advisors. Notable examples of this include The Russian Humanitarian Mission’s chairman, Evgeny Alexandrovich Primakov, and The Russian Military Veterans Brotherhood Association’s Deputy Chairman, Sablin Dmitry Vadimovich.

Four categories of Russian aid entities emerge depending on a senior leader’s connection to the state and organization’s mission. Those that are secular or religiously orientated but align more with the Russian civilian government, and those that are secular or religiously orientated but have more of an affinity to the Russian military (Figure 2).

This diversity allows Russia a degree of finesse in its soft power efforts, providing it different options for aid delivery depending on the type or location of a receiving community. For example, the Russian Orthodox Church can support Christian communities in Syria, while the CRCS can deliver aid near high-risk frontlines. The set-up also gives Russian aid efforts an illusion of separation from state control and the appearance of alignment with international humanitarian norms, while also complementing Russia’s military and political actions.

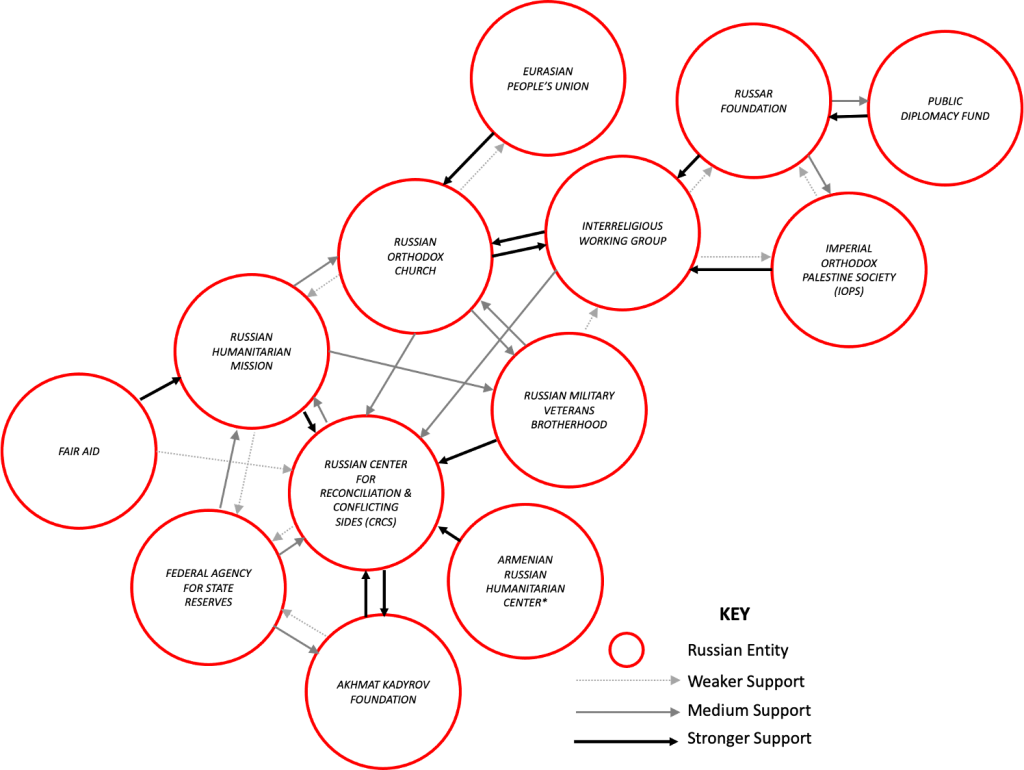

The threat posed by Russia’s closed shadow aid system

Through its aid ecosystem, Russia has established a key instrument of soft power in Syria, one that is closed and free from outside influence. For example, Russian aid entities are not part of the UN-led humanitarian coordination framework in Syria. Nor are they subject to the same strict rules applied to western humanitarian counterparts, such as needing to officially register with the regime or partner with local Syrian NGOs to distribute aid. Russia also does not typically partner with the UN, the International Red Cross, or international donors. Instead, Russia’s shadow aid system relies on two key enablers, the CRCS and, to a lesser extent, the Russian Orthodox Church, to conduct aid in the country (Figure 3). Much as Russia used the Astana talks to prioritize its interests during the Geneva process, Russia uses this protected aid system to rival the existing UN-led system in Syria.

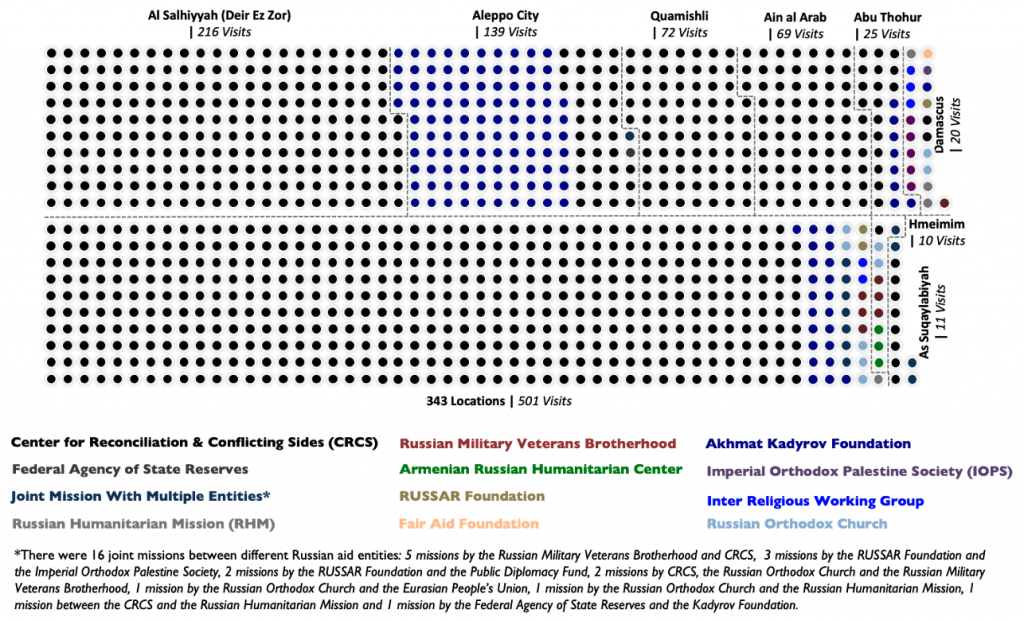

Russia’s aid system also devalues the efforts of the wider humanitarian community. The close connection between the Russian state and Russian aid organizations blur the line of neutrality and independence, two key humanitarian principles that act as an important mechanism to ensure the safety of humanitarians and those they serve. The focus of Russian aid on supply rather than impact, with 98 percent of the 351 locations visited by Russian aid missions frequented less than ten times in two years, could lead to an erosion of trust in the wider aid system (Figure 4). Studies have shown that aid beneficiaries are often unable to differentiate between the humanitarian entities that provide them with aid, meaning that, if Russia squanders trust or is not seen as a reliable or genuine provider of aid, a distrust in the wider humanitarian community could form. This threat is very real, with anti-Russian sentiment growing in southern Syria from opposition groups and government forces and in northwest Syria. How long is it before Russian civilian entities are targeted?

Alternatively, Russia’s actions could create a dangerous false perception about Russian aid being more widespread in Syria than it actually is. Pushing its own alternative narrative about the humanitarian landscape in Syria, Russia’s efforts also takes valuable oxygen and expertise away from the UN and the West. Using aid to promote a favorable view of Russia in Syria deflects messaging away from their hard and destructive military power, re-enforces the regime’s view of the ideal international partnership, and boosts and diversifies Russia’s influence with the Syrian government.

Countering an under-estimated and overlooked threat

Russia’s problematic use of humanitarian action as a soft power tool in Syria will likely remain. However, the threat it poses can be softened by the following recommendations:

- First and foremost, Russia’s use of aid as an instrument of soft power should not be underestimated. Russian aid efforts in Syria—and elsewhere—amplify Russia’s global influence, threaten the wider humanitarian system, and jeopardize established and effective UN-led narratives towards the situation in Syria. This is especially the case if Russian aid delivery is combined with other tools, such as information campaigns, as seen recently in Serbia.

- Second, any engagement with Russia should be done with caution, especially by humanitarian practitioners on the ground, who could inadvertently lend a façade of legitimacy to Russia’s political use of aid. Efforts should be taken to recognize malicious efforts by Russia’s actions early, with an understanding that at present, they are not a reliable partner (Figure 5).

- Third, strong efforts should be made to dilute Russia’s influence over the humanitarian space in Syria. Pressure should be made to transfer Russia’s aid provision to civilian actors, This would soften the military profile of Russia’s shadow aid system, reduce the threat to the wider humanitarian community, and potentially provide an opening to integrate Russian civilian entities within the UN-led coordination system in Syria, which has one of the more robust mechanisms set up for effective aid delivery and countering Russian manipulation despite its issues.

- Fourth, efforts must be prioritized around improving how Russia values humanitarian principles in their own right, rather than as a barrier to military and political efforts in the country. Education should be given on why principles should not be disregarded as they are now and how they are an important tool for building trust and effective long-term partnerships on the ground. In a perfect world, Russia could then see that this would help them build resilience to any potential changes in Russian-Syrian relations in the future, while at the same time not further harming the humanitarian ecosystem in Syria. Education must also be given to Russian entities about the benefits of distancing themselves from the Russian state, especially in their executive board or operational leadership.

For Russia, the strength of its military and political efforts in the country has created an illusion that it is insulated from the Syrian regime’s monopoly over the humanitarian landscape in Syria. However, the elephant in the room is that Damascus has, and always will, control aid delivery in Syria—it just hasn’t chosen to apply this to Russia yet. More than anything, it is this monopoly that needs to change if the Syrian people are to be truly supported.

Jonathan Robinson is an independent researcher with nearly a decade of experience focusing on conflict analysis, humanitarian access, and aid worker security in the Middle East, including Syria. His views do not represent his current or previous employers.

Image: Russian solders are seen at a new corridor of Jisreen-Mleha road where they expect people to arrive from eastern Ghouta, in Damascus, Syria March 8, 2018. REUTERS/Omar Sanadiki