The Gulf is lagging behind on gender equality. Here’s how it can catch up.

When the United Nations (UN) Millennium Development Goals concluded in 2015, and countries around the globe had to reassess their progress in achieving these objectives that were set out in 2000, the truth was difficult to reckon with. Since the ratification of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2016, countries around the world have rushed to accomplish what was outlined as the 2030 deadline approaches amidst unprecedented obstacles and disruptions, like climate crises and the onset of COVID-19.

SDG 5, which is to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls,” includes several targets that aim to eliminate discrimination in the workplace, recognize unpaid female labor, and give women equal rights to economic resources. Today, the Gulf continues to lag behind its counterparts in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in regard to progress on SDG 5. Gender equality in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries continues to face a slow growth pattern despite making commendable progress in the arenas of industry (SDG 9), sustainability (SDG 11), energy (SDG 7), and economic growth (SDG 8).

The Gulf is home to the wealthiest economies in the region, with a moderate growth rate that remained stable even during the pandemic. GCC cities like Riyadh, Doha, Muscat, Dubai, and others have been commended for their rapid economic growth and their ability to push sustainability and innovation forward, hitting all the targets of other SDGs while evading SDG 5—gender equality. With Gulf economies seeking to diversify and prepare for a post-oil future, closing gender gaps in the labor force and ensuring economic rights for women is imperative.

Current situation

While more women are entering the workforce, disparities remain. According to the World Economic Forum’s 2021 Global Gender Gap index, out of the 156 countries measured, Saudi Arabia was ranked at 147, Oman at 145, Kuwait at 143, Qatar at 142, Bahrain at 137, and the UAE at seventy-two. Gulf nations have also scored low in the 2021 Economic Participation and Opportunity index, with Bahrain scoring at 134, Qatar at 136, Kuwait at 137, Oman at 143, and, despite reforms toward gender parity made by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in 2016, Saudi Arabia sits at 149—only seven points removed from the last-ranked country: Afghanistan. The GCC’s low gender equality rates have had implications on regional achievement rates, with the MENA region accumulating the largest gender gap globally (60.9 percent).

At the current pace of gender gap closure in the region, experts predict that it would take MENA 142.2 years to close the gender gap. The lack of female participation in the labor force and their staggering lack of economic participation in the Gulf aren’t reflective of other gender equality indicators like access to education, where GCC governments succeed. Women in the Gulf are one of the most highly educated demographics in the Arab world, mainly due to increased access to education, which was prompted by oil discovery and rapid development in the GCC. Education attainment rates in the GCC have made it evident that unfettered access to education doesn’t ensure similar results in workforce participation for women.

Women attend and graduate universities at higher rates in the Gulf yet still face disproportional unemployment. In Saudi Arabia, women constitute 51.8 percent of university students. However, Saudi women only comprise 33 percent of the labor force. Although this number is double what it was prior to the ratification of the UN SDGs in 2016, social attitudes towards working women still present obstacles to women’s participation in the labor force.

Qatar faces a similar trajectory, with 54 percent of its university-age women being enrolled in higher education compared to 28 percent of its men. Additionally, Qatari women hold some of the highest literacy rates in the region, standing at 98.3 percent. Nevertheless, they have the lowest rates of private sector workforce participation. Similarly, in the UAE, 41 percent of university-age women are enrolled in higher education in contrast to 22 percent of men—though only 42 percent of women are employed or actively seeking work compared to 92 percent of men who are employed or actively seeking work.

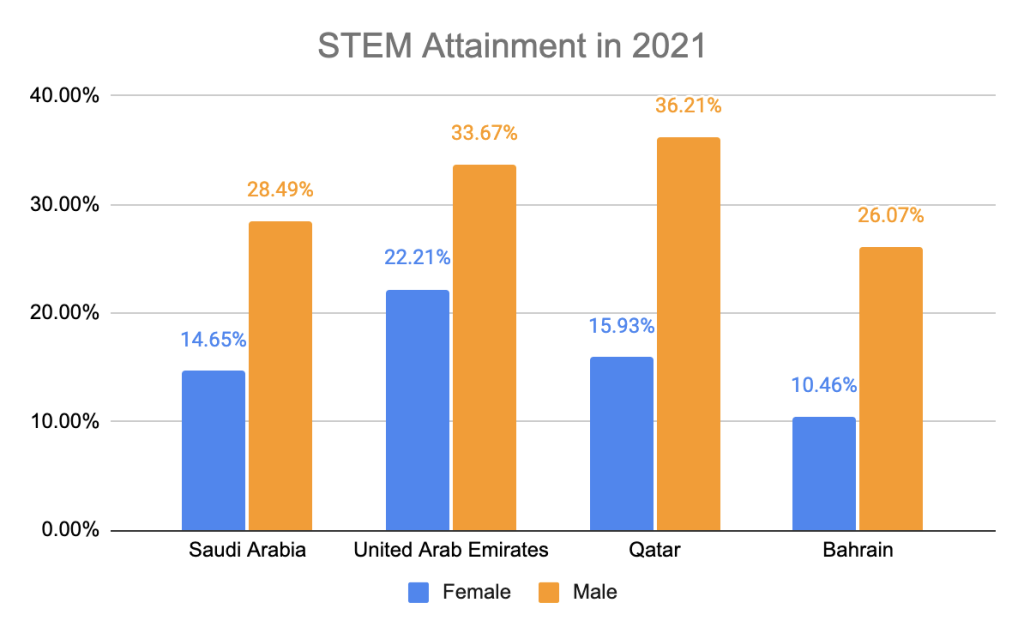

Notably, the sectors with the largest gender gaps in the GCC are the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields. Women’s employment opportunities in the Gulf are incredibly gendered and they are more likely to work in public sector jobs, as they are considered to be socially-respectable work environments for women. By 2030, there will be tremendous potential for technological skills across the global economy, resulting in a significant increase in GDP if women pursue these jobs.

The Gulf’s highly gendered employment patterns and inequities between women and men in STEM will leave women behind and, as a result, the Gulf will fall behind. As digitalization becomes more pervasive across all sectors, economies in the Gulf require more women in the labor force to catch up to global trends. In Saudi Arabia, labor laws specify that women are prohibited from working in dangerous industries, which, in practice, means that they are turned away from more physically demanding jobs. Qatar and Bahrain share these labor laws, prohibiting women from working in hazardous environments, as well as working past a certain time.

Automation and digitalization have already begun to decrease the number of jobs that require physical labor and provide an opportunity for Gulf countries to leverage female employment to compete on a global scale. Oil revenues still contribute a sizable portion of GDP in the Gulf and, as the world begins to slowly shift away from reliance on hydrocarbon resources, economic diversification gives the Gulf a window to benefit from expanding female employment across all sectors. Gulf states will surely incur the costs if they fail to seize this opportunity.

Despite symbolic reforms by Gulf governments, many GCC countries have remained at the bottom of the Global Gender Gap Index for years and are projected to continue doing so. Though Saudi Arabia and the UAE are leading the region in historic changes, emphasizing substantive changes to minimize gender inequities and increase women’s economic possibilities are important.

Moving Forward

It is evident that the current progression of GCC states in advancing gender equality in economic participation and the labor force is insufficient and that the current pace of action may not achieve UN SDG 5 by 2030—though all hope isn’t lost. Many Gulf nations have already instituted several socioeconomic blueprints with deadlines that coincide with the 2030 UN SDGs, such as Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, Bahrain’s Economic Vision 2030, and Qatar’s National Vision 2030.

These national agendas have all included clauses that cover objectives to achieve gender equality and improve the conditions of women across the labor sector. Still, Gulf nations can do more by enacting several policies to reverse previous impediments and ensure the region is on track for the 2030 deadline. The following policies can help the GCC fulfill SDG 5 by 2030 and thereby enhance regional economies by increasing female labor force participation:

- GCC governments should lift obstacles in the workforce for women by addressing gendered discrimination in the workplace, occupational and sectoral segregation, amplifying women’s value in the labor market, and supporting women to maintain and advance their careers within non-traditional sectors like STEM and growing innovation spaces, such as digitalization and the clean energy industry.

- Female entrepreneurship has the potential to boost household earnings and national economies. GCC countries must enhance entrepreneurship development opportunities for women through increased financing, training opportunities, and gender-smart procurement. Gulf governments should also implement tax reductions, facilitate loans, bank guarantees, micro-credit systems, award grant practices, and equitable registration procedures to enhance female-run enterprises across the region.

- Gulf states should implement care policies and provisions that promote a sustainable work-life balance for women in the labor force. GCC policymakers must pass laws that strengthen support for women in the labor force who balance traditional caretaker and professional roles, such as the UAE’s Federal Decree Law No. 33, which protects women from labor market discrimination and provides maternal and childcare benefits and resources to working women.

- Finally, policymakers in the Gulf should adopt legislation that requires employers to uphold gender quotas in the workplace, specifically within the STEM and business sectors. Implementing gender quotas in tandem with the social policies mentioned above could fast track progress in gender equality achievement by creating a “shock” effect on embedded male-dominated organizational systems. GCC policymakers should look to existing gender quota legislation in countries like Norway and the UAE and initiatives such as Athena SWAN, which works “to enhance gender equity in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM).”

Conclusion

The dialogue for gender parity in the workforce is still ongoing, but GCC nations have the advantage of prioritizing female employment in tandem with economic diversification. Gulf women are the most educated demographic while being the least employed and largely excluded from the labor force. As the UN SDGs’ 2030 deadline approaches, harnessing female inclusion in nontraditional sectors like STEM and business is critical as the GCC transitions to a post-oil economic landscape.

Salwa Balla, is a Young Global Professional with the Rafik Hariri and Middle East Programs.

Iman Mohamed, is a Young Global Professional with the Rafik Hariri and Middle East Programs.

Further reading

Wed, May 11, 2022

Emerging market investments are shrinking. How will MENA countries hit FDI targets?

MENASource By Amjad Ahmad

A US economic slowdown or a recession couldn’t come at a worse time for emerging markets, particularly those in MENA, where most are fighting chronic unemployment, slowing growth, and higher debt levels.

Tue, Jan 18, 2022

Is the GCC ready to embrace sustainable finance?

MENASource By

To avoid falling behind on their grand economic growth ambitions, Gulf Cooperation Council countries should act decisively by putting sustainable finance policies at the top of their agendas.

Mon, Nov 29, 2021

Startups aren’t just hip. They’re also the key to unlocking youth unemployment in MENA.

MENASource By

The MENA region has a pressing unemployment challenge. While many attempts are underway to address this problem, the solution could lie in its growing startup scene.

Image: An investor watches stock prices on a computer screen in the women only section of the Kuwait Stock Market in Kuwait City October 13, 2008. REUTERS/Stephanie McGehee (KUWAIT)