As the world is focused on the US elections, the country of Myanmar is also set to go to the polls on November 8. While Myanmar gained attention for the restoration of some democratic rights in 2010 following years of military rule, the upcoming election is at risk of undermining this progress amid widespread political repression and human rights violations. There is strong evidence that the elections will be neither free, fair, nor inclusive, as a result of the suppression of free speech, use of hate speech, and cancellation of voting in several regions. Myanmar’s authorities have used the COVID-19 pandemic as a helpful distraction from these democratic violations and other domestic policy failures, including its own inefficient handling of the COVID-19 crisis and the struggling economy.

Suppression of free speech, fanning to hate speech, and cancellation of voting

The government has blocked websites of organizations and advocates such as Justice for Myanmar, a Myanmar human rights group, to suppress opinions critical of the military and the ruling government. The Myanmar Election Commission has also threatened criminal sanctions against the leaders of a ‘no-vote’ campaign. It now requires that all political parties submit their campaign messages for censorship before being broadcasted on state-owned radio and television stations. Human rights groups report that their officials have been harassed and intimidated by authorities. Internet restrictions remain in place in Rakhine and Chin States—regarded as the world’s longest-running internet blackout—limiting access to information before the upcoming elections.

One of the government’s most concerning actions has been the use of Section 505(b) of the Penal Code to prohibit speech that may cause “fear or alarm in the public” and lead others to “upset public tranquillity.” Dozens of students have been charged or are facing arrest for offenses—which include up to two years in jail—for distributing pamphlets demanding an end to the fighting in Rakhine State and immediate termination of all internet restrictions.

Hate speech has also been fueled by State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi herself. As COVID-19 cases surged in Rakhine state back in June, Aung San Suu Kyi threatened to “severely” punish anybody crossing into the country illegally, as well as those who harbor undocumented arrivals. The context of this rhetoric is crucial: Rakhine state remains turbulent due to the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingyas in 2017. Soon after the state media broadcasted Aung San Suu Kyi’s speech, hate speech against the Rohingya proliferated in popular local media outlets and social media platforms. Amidst this racist fervor, a Buddhist Rakhine lawmaker blamed the Rohingya for the outbreak and demanded further segregation between the Buddhist Rakhine and Muslim Rohingya populations.

Another major concern has been the cancellation of polling in several areas, mostly in ethnic minority states. The Election Commission announced during mid-October that, since there is conflict in parts of Rakhine, Kachin, Kayin, Mon and Shan, and Bogo regions, free and fair elections cannot be guaranteed and thus polling would be cancelled.

Bleak COVID-19 situation and economic slowdown

In addition to a low testing rate of 5.84 tests per thousand (as of October 7), the Myanmar Health Ministry has been inconsistent and non-transparent in its reporting of cases.

Myanmar’s authorities were slow to grasp the seriousness of the risk facing the country. During late January, a presentation to Yangon Hospital staff highlighted relaxed official attitudes towards both the then looming pandemic as well as the racially charged nature of the country’s politics. Staff were shown a slide presentation that included the declaration: “Don’t be so afraid of the coronavirus. It won’t last long because ‘made in China.”

Initially, many in Myanmar perceived that the government had COVID-19 under control, with just about four hundred confirmed cases and six deaths from late March to late August. However, a spike in cases since August has changed things dramatically. Hundreds of COVID-19 cases are now announced daily in Myanmar and the government has re-imposed restrictions on domestic movements across the country while the commercial capital, Yangon, is under partial lockdown.

Moreover, the economy remains sluggish. While policy liberalizations had catalyzed growth in Myanmar’s economy at the beginning of the decade, under the administration of the ruling National League for Democracy party (NLD), gross domestic product growth has slowed, the currency has weakened, and foreign investment stagnated.

Role of international actors in fueling racism

MVoter 2020—a donor-funded election app designed to provide information to voters during the upcoming election—has now become a potential catalyst for racially-driven politics. A Stockholm-based organization developed the app in partnership with the Asia Foundation and Election Commission of Myanmar. On the surface, the app appears innocuous, as it merely tries to provide data on approximately seven thousand candidates who are running for office.

However, many, including the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, have criticized this app. This is because it provides information on a candidate’s race and religion, as well as that of their mother and father, thereby incentivizing racially-inspired political decisions during election time in an environment already strife with ethnic and religious tensions. This kind of data—which is based on Myanmar’s official classification of 135 “national races”—is one of the primary reasons for the statelessness of the Rohingyas. Justice for Myanmar says that such data have “been used as a pretext to disqualify Rohingya candidates and disenfranchise Rohingya voters from the election.”

Need for international attention on Myanmar’s national elections of 2020

Last year, Aung San Suu Kyi’s ruling NLD party was faced with corruption scandals that have undermined the party’s pledge to clean up the government following decades of military rule. In July 2019, Industry Minister Khin Maung Cho stepped down after facing allegations of inappropriately handling procurement procedures. Now, when the country faces a flagging economy and dreary COVID-19 situation, people’s attention to such important issues are being diverted through the promotion of hate speech and the suppression of dissenting voices.

Over the years, the international responses to Myanmar’s abuses against its ethnic minority communities, especially the Rohingyas, is not backed up by any policies to support growth of a democratic or ethnically and racially inclusive environment in the country. Its role during this election might be regarded as ambiguous at best given the development and use of a tool such as the mVoter2020 app. Stiffling of free speech, use of hate speech, and cancellation of voting are hallmarks of the 2020 national elections in Myanmar, something that the international community must not ignore despite COVID-19’s near monopoly on global media and policy.

Dr. Rudabeh Shahid is a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Further reading

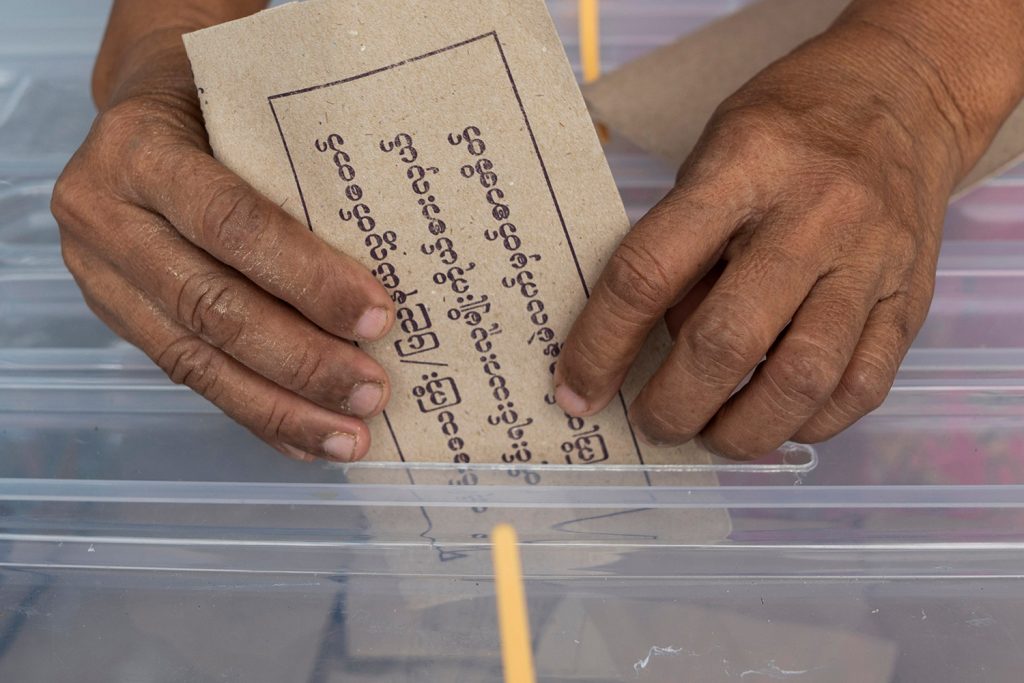

Image: A woman cast her ballot during the early voting ahead of the November 8 general election, amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) spread in Yangon, Myanmar, October 30, 2020. REUTERS/Shwe Paw Mya Tin