Ahead of its presidential election, Senegal shows that democracy requires the rule of law

Senegal has long been viewed as a haven of democracy in West Africa. Since achieving independence from France in 1960, the country has held regular elections and remained under democratic rule. Senegal’s democratic stability is commendable, particularly considering that many of its neighbors—from Guinea to Burkina Faso—have all experienced military coups. The recent presidential election, however, has shown cracks in Senegal’s traditionally strong democracy. While elections are ultimately slated to continue after a period of uncertainty, the events in Senegal have uncovered larger issues related to the rule of law, a vital determinant in sustaining democracy.

In the past three years, Senegalese President Macky Sall and his ruling party have engaged in some practices that have strained the rule of law and judicial independence. Since 2021, more than one thousand protesters and journalists associated with opposition parties have been jailed, with human rights groups reporting abuses such as arrests without warrants and unfair trials. Moreover, the excessive use of force during protests has led to at least sixteen deaths.

Yet arrests and detention have played just one part in the increasingly complex puzzle. In early 2024, Senegal’s election authority, the Constitutional Council, disqualified top opposition candidates Ousmane Sonko and Karim Wade from the presidential election, citing a defamation charge for Sonko and dual citizenship status for Wade. Critics, however, labeled these rulings to be politically motivated attempts to disqualify opposition candidates. Sonko faced challenges at every turn, from logistical forms to a denied defamation appeal, while Wade had renounced his French citizenship. Despite the legal justifications from the Council, the struggles opposition parties faced in getting candidates on the ballot ignited pushback.

In response to perceived bias in the candidacy process, the parliament voted on February 5 to delay elections until December 2024. While Sall and the ruling party claimed the decision was aimed at allowing the Constitutional Council and legislature the chance to agree on who to include on the ballot, opposition members viewed this as a tactic to keep Sall in power longer and ensure a better election outcome for his party. This sweeping decision—made after opposition parliament members were forcibly removed from the National Assembly—was met with widespread criticism. Scholars cited clear violations of Senegal’s constitution, and civil unrest erupted.

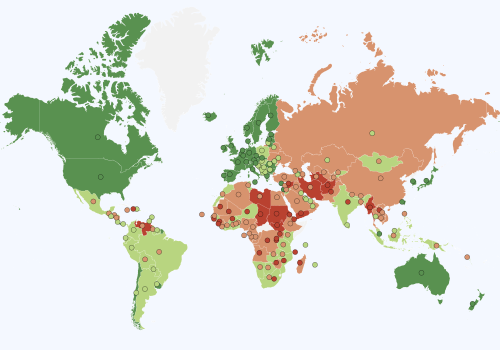

Senegal’s legal issues come as a surprise considering the country’s history as a stable and promising democracy. In the Freedom and Prosperity Indexes, Senegal has scored above the global average in the overall Freedom Index as well as the political and legal subindexes. Senegal has been particularly strong in judicial independence and effectiveness. One of the five indicators in the legal subindex, judicial independence and effectiveness measures the degree to which laws are respected and whether violations are dealt with in a fair manner. Senegal has consistently scored highly in this metric, progressing toward the levels of the world’s freest countries. In 2021, however, the country’s score began decreasing, suffering the effects of the increasingly hostile practices toward political opposition.

The recent practices observed in Senegal, including election postponements, pretrial detentions, and disqualified opposition candidates, undermine the rule of law and erode public trust in the government. Indispensable for a flourishing and fair society, the rule of law shields citizens from government overreach and ensures an equitable process without favoritism. A lack of the rule of law leads to declining trust in government, which in turn may develop a vicious cycle of radicalization and create a disillusioned generation alienated from electoral politics.

Despite the concerns, there are signs of democratic resilience. On February 15, the Constitutional Council overturned the decree to postpone the election indefinitely. Shortly after, Sall and the parliament rescheduled the election for March 24. Moreover, more than three hundred prisoners arrested during demonstrations were released. A glimmer of hope is present for opposition politics as well. Though Sonko remains disqualified, his hand-picked alternative, the previously jailed Bassirou Diomaye Faye, was released from prison and will be permitted to run. With the date and candidates set, Senegalese citizens can now turn their attention toward the upcoming election.

But democracy requires more than just elections. It requires an independent judiciary and strong rule of law for its sustainment. As the Freedom and Prosperity Indexes show, Senegal has long scored high in democracy rankings. In a year with the highest election turnover in history, watchdogs and stakeholders may take solace in the fact that the democratic process in Senegal was eventually able to proceed. But the country’s underlying concerns on political violence and a leader reluctant to release power remain a challenge. For Senegal to truly cement its status as a haven of democracy, the country must prioritize judicial independence and the rule of law, ensuring that elections and transfers of power are fair and peaceful.

James Storen is the program assistant for the Freedom and Prosperity Center.

Annie (Yu-Lin) Lee is a young global professional in the Freedom and Prosperity Center.

Further reading

Thu, Jun 15, 2023

Freedom and Prosperity Indexes

Trackers and Data Visualizations By

The indexes rank 164 countries around the world according to their levels of freedom and prosperity. Use our site to explore twenty-eight years of data, compare countries and regions, and examine the sub-indexes and indicators that comprise our indexes.

Thu, Jan 11, 2024

False promises: The authoritarian development models of China and Russia

Report By Joseph Lemoine, Dan Negrea, Patrick Quirk, Lauren Van Metre

Are authoritarian regimes more successful than free countries in offering prosperity to their people? The answer is decidedly no, yet China and Russia advertise the “benefits” and “promise” of their authoritarian development model. This paper showcases why and how the authoritarian development model is inferior to that of free societies.

Thu, Apr 20, 2023

Tackling food insecurity in Africa will require securing women’s rights. Here are two ways to start.

New Atlanticist By James Storen

Policymakers should equalize inheritance rights and support women's entrepreneurship as ways to enhance food security.

Image: Senegalese presidential candidate Anta Babacar cheers her supporters during her electoral campaign caravan in Thiaroye on the outskirts of Dakar, Senegal March 10, 2024.REUTERS/ Zohra Bensemra