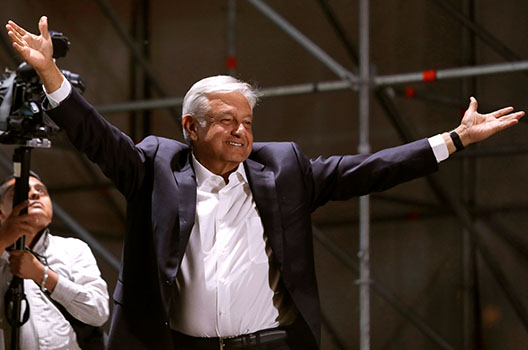

After overturning the Mexican political establishment and capturing an astounding fifty-three percent of the vote, President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador must face his next challenge: governing.

After overturning the Mexican political establishment and capturing an astounding fifty-three percent of the vote, President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador must face his next challenge: governing.

Although his election on July 1 was “completely expected,” AMLO, as the president-elect is known throughout the country, must begin to make tangible progress on the many protracted challenges facing his country, according to Valeria Moy, a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center and director of México, ¿Cómo vamos?

For Jason Marczak, the director of the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center who joined Moy on a July 2 press call, AMLO’s victory “was a change election for Mexico,” which saw AMLO and his National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) party win not only the presidency, but projected majorities in both the Senate and Chamber of Deputies, as well as several key governorships and state legislative races.

Despite the large margins of victory—AMLO’s closest competitor captured only twenty-three percent of the vote—Marczak argued that AMLO must attempt to heal the nation after a bitter election.

“There is a deep polarization in Mexico right now. One of the major challenges that AMLO will have will be how to construct some of those bridges,” to those who opposed him, he said. Critics, Marczak said, “have a lot of trepidation. . . about what will transpire during his government.”

The heightened polarization resulted in considerable spreading of online disinformation during the election, Marczak said, highlighting the work the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab conducted in the run-up to the election. Despite the high levels of disinformation, Marczak noted that they affected all sides and parties in the election and that the Atlantic Council was “not able to verify coordinated disinformation from other nation states.”

As AMLO transitions from candidate to president, he will need to translate his lofty campaign rhetoric into tangible successes in the short term, Moy argued. “Some of [AMLO’s] messages throughout the campaign were really simplistic. . . I don’t think they will be enough to tackle the big problems,” she said.

On corruption, which Moy said “was the issue of the campaign,” AMLO has made vague promises on his personal character and leadership in dealing directly with the issue, but must be prepared to engage civil society, international organizations and Mexican governmental institutions to make real progress. As Moy pointed out, several of AMLO’s close associates have already been accused of corruption, and how he responds to these accusations will be critical to the success of his anti-corruption campaign.

Marczak echoed the belief that AMLO will need victories at the beginning of his term, and pointed to the violence directed at politicians and journalists during the campaign as a first task for the new president. Finding and convicting those responsible for the deaths would provide AMLO with tangible evidence that he can succeed at stemming violence in Mexico, something his predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto, was never able to obtain.

AMLO’s new administration will also have to take control of the ongoing negotiations with the United States and Canada to revise the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Moy believes AMLO’s team is “eager to reach a good deal,” but will need to work closely with the outgoing Peña Nieto negotiators to ensure a smooth transition and to retain the considerable knowledge the current team has accrued.

Marczak thinks that AMLO will “not be going back to the drawing board” on NAFTA, but the new president’s experience growing up in southern Mexico may give him an eye on how NAFTA can be changed “in a way that benefits the country as a whole,” rather than just the northern states.

Beyond NAFTA, Marczak believes the “self-described nationalist” AMLO will work with international partners, including the United States, “when it benefits Mexico.” Marczak does not “see [AMLO] acquiescing to US demands on issues” unless there is a clear benefit for Mexico. Moy added that AMLO will focus primarily on “internal, domestic policy,” only turning to international affairs after addressing the many domestic challenges facing his administration.

As Marczak put it, AMLO’s focus “is going to be on general improvements in security across Mexico,” not just the border region, despite the likely pressure he will face from Washington.

AMLO will have five months to prepare his administration before taking office on December 1. Both Moy and Marczak stressed the importance of the transition to AMLO’s future success, which will include working with Peña Nieto’s team on both ongoing NAFTA negotiations and a new budget.

AMLO will take power with a historic mandate, both chambers of congress under his control, and significant support in state governments, but will need to translate this power into tangible success to maintain this momentum.

As Moy put it, the campaign is over, “now the reality will prevail.”

David A. Wemer is assistant director, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

Image: Mexico's next President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador gestures to supporters, in Mexico City, Mexico July 1, 2018. Picture taken July 1, 2018. (REUTERS/Alexandre Meneghini)