Following the last European Council on October 17-18, French President Emmanuel Macron was strongly criticized for blocking the opening of negotiations with North Macedonia and Albania for potential EU membership. European Council President Donald Tusk, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, and EU Commissioner for Enlargement Johannes Hahn—who even apologized directly to Skopje and Tirana for the delay—expressed disbelief and anger over the French veto, especially against North Macedonia. Despite the efforts of the Finnish presidency to push for decoupling both cases and reaching a compromise, Macron’s decision prevented either candidate country from reaching the next stage of the enlargement process.

Numerous commentators have laid out the potential negative consequences of the French decision for the Balkans and the European Union. Assuming that the decision was barely related to North Macedonia and Albania—and instead a reflection of internal French politics—it is nevertheless important to assess whether or not, from a strict French standpoint, it was a mistake.

It was widely anticipated, at least since last European Council in April, that Albania did not have a chance to obtain an invitation for negotiations due to French, Dutch, and Danish opposition. Therefore, the focus here—regardless of whether or not such position is fair to Tirana—will be on North Macedonia, since France stood alone against the other twenty-six EU member states in opposing negotiations with Skopje.

Why is France afraid of enlargement?

Macron arrived at this decision for both short-term opportunistic reasons and important long-term considerations.

In the short term, Macron argued that the current EU enlargement process was not working, that efforts by Albania and North Macedonia towards meeting EU accession criteria were not sufficient, that any leverage the EU had to push for reforms would be lost should negotiations start, and that decoupling the two countries could pose security problems due to the high number of ethnic Albanians in North Macedonia. The last point can be dismissed as baseless. As for concern over the EU enlargement process, France has never mentioned these concerns before and has never proposed solutions to fix the process, as opposed to the European Commission and others who did here and here. In respect to Skopje and Tirana’s reform efforts, it can always be argued that candidates are not doing enough. The issue is whether keeping them away or letting them into the process provides more impetus for reforms. Greece had blocked North Macedonia from EU enlargement for a decade with disastrous consequences for Skopje, which did not cause significant momentum for reform, as Macron’s argument would imply.

Behind this first set of reasons lie the real concerns, on which Macron has been rather vocal and consistent since his election. First, he argues that twenty-seven (post-Brexit) members are already too many voices to have an effective political union able to make decisions. Yet he has also argued that the EU decision making processes and institutions are dysfunctional, supposedly regardless of the number of members. Which one is it? Are the number of voices around the table causing the dysfunction or the design of the institutions themselves? Would Paris block Scotland or Iceland from membership as well because twenty-seven is too much already? If it is a matter of institutional reform, the Lisbon Treaty already has some reforms that have not been implemented. Moreover, research tends to show that the “enlargement versus deepening” question, which France has revived since 2017, is more complex than it seems. Namely, reforms come because the Union enlarges, not the other way around.

Second, historically, France has always been reluctant about enlargement, from the UK in the 1960s to Spain in the 1980s. Why? Because it weakens Paris’ influence and dilutes the political project of the EU from what France would wish it to be—more integrated and reflective of France itself. In addition, the 2004 Eastern enlargement remains a huge political trauma, as many argue it caused the failure of the 2005 European Constitution referendum and fueled broad reluctance to enlargement within French public opinion. The 2004 enlargement moved the epicenter of Europe—in the eyes of Paris—towards the East, to Germany. Therefore, Paris sees Berlin as the main winner of the last fifteen years, as Germany took full advantage of the integration of its former communist neighbors. Likewise, France sees the Balkans as being part of Germany’s sphere of influence, meaning enlargement should be seen from that standpoint as an element of a broader French bargain with Germany. Namely, Berlin has stonewalled most of Macron’s reform ideas on issues such as the eurozone, and Macron is now holding a process that matters more to Germany, for economic and security reasons, than to France.

The belief that Paris is motivated to block new enlargement negotiations over fear of fueling the populist far right in France should be dismissed as irrelevant, not only because enlargement is a very peripheral issue that would not occupy voters’ minds during a general election, but also because by regularly opening or entertaining debates on immigration and Islam within France itself, the French government doesn’t need Albania to animate the populist far right at home.

Taking two steps back

Beyond the negative consequences for the EU and the region, Macron’s decision is also harmful for France itself, based not only on Macron’s liberal ambition for Europe described in his 2017 Sorbonne speech, but also on France’s very interests in the Balkans.

While Paris retired years ago from the Balkans and the area appears to be not crucial for its diplomacy, it has four key objectives in the region:

- Redesigning the enlargement procedure by prioritizing establishment of the rule of law and promoting governments sincerely attached to the EU and its values

- Fighting illiberalism in the Balkans as anywhere else in Europe

- Having enough credibility to reemerge as a serious actor in the region in the frame of its “strategy for the Balkans”

- Actively promoting and assisting in the resolution of the Serbia-Kosovo issue

By strongly supporting the government of North Macedonia from the start and granting it the opening of negotiations, it would have been possible to create a virtuous circle in the region and kill four birds with one stone. It would have reaffirmed France’s desire for the enlargement process to be about values and attitude, rather than just ticking boxes. It would have sent a strong signal to illiberal regimes in the region and their people about the real path to European accession. It would have placed France at the center of the game in a positive way and given it political credit to demand and get more done. It would have shown Serbia that a government willing to make a serious sacrifice, like Prime Minister Zoran Zaev’s government did, was not unrewarded, thus placing France again at the center of the European effort to solve the Serbia-Kosovo issue. Moreover, all of this could have been attempted at zero political cost into a win-win situation for France, the EU, and the Balkans.

President Macron chose to do exactly the opposite. He spent serious political capital (twenty-six members in favor against just Paris) on a topic and a country that, again, are not seen as a top priority. Hence a lose-lose situation for France, the EU, and the Balkans. The decision will see no breakthrough on the reform of the accession process, the strengthening of illiberal regimes, absolute loss of political credit in the region, and the loss of the only incentive that could be used on Serbia (even if last polls show that Serbs are not ready to trade Kosovo for the EU integration). Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić immediately reacted to the French decision by stating that the EU’s words were meaningless. Since it was not in Vučić’s interest to solve the issue of Kosovo in the short term (as argued here), how does France hope to convince him otherwise now that it has shown that such a move would not result in progress towards the EU?

All in all, considering the four objectives France has in the Balkans, it seems that Macron’s decision destroyed the possibility to reach them, at a high political cost with both his EU partners and in the Balkans.

Ironically, on October 24, the Renew Europe group in the European Parliament, which includes Macron’s party, added its voice to other groups voting for a resolution supporting the opening of negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia, further reinforcing the isolation of Paris on the topic.

Stop the double-talk

It is high time France took a side between no enlargement whatsoever and enlargement in return for tangible reforms in both Brussels and the candidate countries. If it is the latter, Paris must adopt a constructive instead of destructive role. If it is the former, Macron should have the decency to say it instead of humiliating countries and people by postponing decisions every six months. People in the region are not stupid, they know that their countries are not welcomed and are leaving en masse, not as asylum seekers or illegal immigrants, but as legal workers in Germany, Austria, and other EU countries.

If the EU is to become a serious political and military actor one day, as Macron aspires, the Balkans is the most obvious—perhaps the only region—in which such power can materialize. But the Balkans is also the place where the EU has failed the most for the last thirty years. Balkan countries are still relying more on the United States (North Macedonia and Montenegro recently became NATO members), despite all the bizarreness of the Trump administration, than on the EU, not to mention other powers like China, Russia, or Turkey. France cannot say that it wants to anchor the Balkans closer to the EU, and “en même temps,” kill its prospects of actually doing so.

Loic Tregoures, PhD, teaches political science at Catholic University of Lille. He’s specialized in Balkans.

Further reading

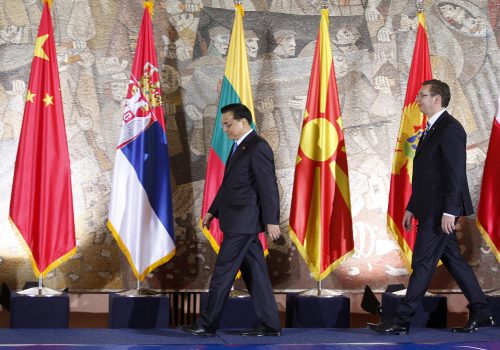

Image: French President Emmanuel Macron attends the second day of the European Union leaders summit dominated by Brexit, in Brussels, Belgium October 18, 2019. REUTERS/Toby Melville