India is between a rock and a hard place. The lockdowns have not reduced the increase in coronavirus spread and its economy has cratered. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has just announced Rs 20 Trillion (approximately $260 billion) package amounting to 9.6% of gross domestic product (GDP)—called “Aatma Nirbhar Bharat” which translates to self-reliant ( self-dependent) India—to save lives and livelihoods and reset the economy. But, if it will be enough will depend on what it contains and more importantly on how it is implemented.

Modi has compared the battle against the virus to the Maha Bharata, the epic battle from Hindu mythology between good and evil. That ancient battle lasted eighteen days, and in announcing his first lockdown of the Indian economy for twenty-four days on March 24, Modi said he would have the virus licked in that same timeframe.

But some fifty days on, India is nowhere near even containing the pandemic. The number of cases, while still below Europe and North America is rising rapidly crossing 75,000 with almost 2,500 recorded deaths. Given its low testing capacity and under-reporting of deaths, the actual numbers are already much higher. India‘s COVID-19 curve has not peaked and is rising linearly if not exponentially. The lockdowns have not reduced its spread but have hammered the economy which was struggling even before the lockdowns.

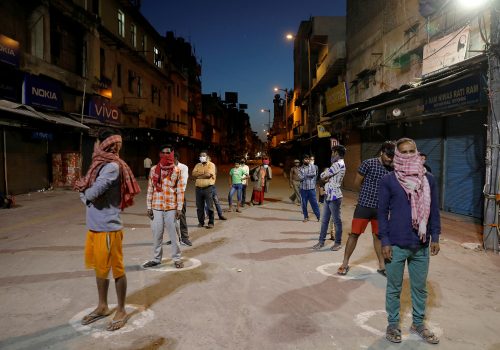

Some say the dramatic lockdowns—announced without any warning—may end up killing more people with some 300 million people living on the edge of poverty. At a minimum, the economic and social impact has been huge. The drastic lockdowns created an embarrassing nightmare for some 150-200 million poor unemployed migrant workers who were left stranded trying to get home to their villages. India’s coronavirus numbers appear low compared to other countries—some attribute it to the compulsory Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine and others to India’s young population. No one really knows.

An initial package of cash to poor women and elderly and free food of around Rs 1.7 trillion ($22 billion), was too little. Despite the Reserve Bank of India’s efforts to cushion the impact on business with sharp cuts in interest rates and liquidity boosting measures which amounted to Rs 6.5 Trillion ($87 billion), the economy shrank sharply and is now projected to grow by less than 1 percent in fiscal year 2020-21 (April 20 to March 21), with some predicting even a decline. A quick survey done by FICCI shows that 80 percent of business are showing a decline in cash flows and a CMIE survey shows 27 million youth between twenty to thirty years have lost their jobs and the unemployment rate shot up to 27 percent in April 2020.

The Modi government inflicted an own-goal with a bungled demonetization in 2016, which ended up creating enormous unnecessary misery—especially for the poor. This time it was forced to deal with an external virus, but once gain blundered in its initial response. Other than some half-hearted attempts at airport screening it delayed actions until March 24 when it announced a dramatic lockdown with no warning. Modi even welcomed the US president to a Namaste Trump rally on February 24 at India’s largest cricket stadium as a payback for the Howdy Modi rally in Houston Texas a few months earlier.

This was a time when smart countries like South Korea, New Zealand, Taiwan, Germany, Norway, and Finland were preparing for the worst. Even within India the state of Kerala followed a very different approach. Kerala, India’s most progressive state, took the global warning seriously and appears to have brought the virus under control with a very active strategy of testing, screening, and isolating that the rest of India must emulate but does not appear to be able to do.

The focus now has shifted to living with the virus and reviving the economy. But while that shift has come in many countries after the COVID-19 curve has peaked, India’s change in approach has come while the curve is still rising—probably realizing they cannot control it anyway given its underfunded health system and the lockdown is probably doing more damage than good. India’s public health spend at 1.3% of GDP was amongst the lowest in the world.

How large is my package?

In shock and awe style, the headlines focus on the size of India’s latest package—at 9.6% of GDP it’s the fifth largest in the world. It has even boosted stock markets in India and Indian listings in global markets. But India’s number includes liquidity easing estimates from its central bank which amount to almost half of the package. Even without these the package is large—close to 4.5-5.0% of GDP—and about the same size as the UK’s and the fiscal package India provided at the time of the Great Recession in 2008. But what will matter in the end is not its size, but its impact on lives and livelihoods. China and South Korea have much smaller packages and are already on their way upwards, as they have much better control over the virus. That in the end may matter more than the size of the stimulus packages.

The size of coronavirus packages by country

| Country | Share of GDP (%) | Country | Share of GDP (%) |

| Japan | 21.1 | Italy | 5.7 |

| United States | 13.0 | UK | 5.0 |

| Sweden | 12.0 | China | 3.8 |

| Germany | 10.7 | South Korea | 2.2 |

| France | 9.3 | India | 9.6 (4.5-5.0) |

| Spain | 7.3 |

Where will the funds go? The full package will be announced in six tranches. In the first tranche a big focus is on the Micro, Small and Medium (MSME) sector. Major steps for the revival of the MSME sector have been announced, including collateral free loans of Rs 3 Tr ($40 b) for MSMEs, which will benefit forty-five lakh units so that they can resume work and save jobs. For stressed MSMEs, subordinate debt provision has been announced. The definition of MSME’s has been changed to go up to Rs 1 cr ($133,000) and sales Rs 5 crores ($650,000). How quickly will the funds get to the firms will matter hugely as many are struggling to survive?

Other elements include relief on employee provident funds, cuts in withholding tax, and extension of tax filing deadlines to November 30 from July 31. Money is also set aside for non-bank financial companies in the form of partial credit guarantees (20 percent to be covered by government) and a one-time emergency liquidity injection to DISCOMs but with no assurance that they will use it to pay providers of energy. A second tranche provides support to farmers, rural landless, and migrants. For migrants it provides free food without ration cards, a portable ration card for the future, and other support such as subsidized housing. Farmers get support as well for extensions of loans, but big bang reforms such as removal of the Agricultural Produce Marketing Act, which would free farmers from the clutches of captive buyers, is still awaited. More details will follow in the next four tranches.

There are no details on how the package will be financed. A fiscal hole of around 4.5% of GDP even before the crisis is likely to go up hugely—as tax revenues will fall by at least 2-3 percent of GDP. The disinvestment receipts of around 1 percent of GDP will not materialize this year. Oil windfall—due to low oil prices—may amount to around 1 percent of GDP, but some of this must be netted out with drop in remittances (0.25% of GDP). So the fiscal deficit could rise by close to 7-8 percent of GDP. It will be unlikely that this can be financed by borrowing in internal markets and India may have to borrow abroad and have its central bank buy government paper—no other recourse will be acceptable to the Modi government such as seeking International Monetary Fund (IMF) support. India has huge reserves—$450 billion—and does not face a balance of payments problem, if anything it may improve if oil prices remain below $40 per barrel.

A reset for the 21st century

India’s package is showcased not just as a rescue package to nurse the economy back to health but in typical Modi flourish to reset India for the 21st century: a strong self-reliant India. Modi’s penchant for literation come through in defining needed refoms in four “L’s”; labour, land, liquidity, and legal frameworks. This is a welcome focus on reforms in factor markets that India has badly needed as a reset to the 1991 reforms which liberalized the economy. Those reforms had run out of steam and need a reboot with a crying need for the second stage factor market reforms. This crisis brings an opportunity to finally go after them and get away divisive politics to realize Modi’s promise of “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Vishwas ”—Unity, Development, and Trust.

But how it will be done will matter as well. India’s labor laws were a huge hindrance to investment in companies with over one hundred workers—which led to a missing middle in Indian manufacturing, the category which is considered the most competitive in many global industries. The Indian government had demitted labor reforms to the states and some like Rajasthan and MP had carried out some timid reforms.

Last week, India’s largest state Uttar Pradesh used this crisis to abolish most labor laws and allow firms to lay off workers and other states are likely to follow. While India needs more labor market flexibility, whether this qualifies as a reform remains to be seen—as increasing the ability to hire and fire workers must also be accompanied by stronger protections on unemployment insurance, injury protections, and medical and leave provisions.

While both the prime minister and the finance minister re-iterated that India was not turning inward, the reality is that India was already growing more protectionist even before the crisis. The focus on self-reliance could easily degenrate into a return to India’s import substitution regime of the 1970s and 1980s when India became uncompetitive and struggled to grow above 4 percent—eventually leading to a balance of payments crisis in 1991. While India also strives to attract more foreign direct investment—especially firms leaving China—these are just pipe dreams unless India improves competitiveness, unlikley under high tariff and non-tariff barriers. And the dream of making local brands global requires a very big focus on global competititveness, whereas import subsitution makes these local firms content to sell shoddy products at inflated prices to captive consumers.

India’s dreams of becoming a $5 trillion economy by 2025 is now impossible. Its GDP will stagnate at $2.7 trillion this year at best. Reaching $4 trillion by 2030 will now be a struggle if India grows at 4 percent per annum—the old Hindu growth rate. If it does not turn inwards and focuses on making India globally competitive it may reach $5 trillion by 2030. That must be its new goal.

Ajay Chhibber is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Further reading:

Image: People wait to receive free food at an industrial area, during an extended nationwide lockdown to slow the spreading of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in New Delhi, India, April 23, 2020. REUTERS/Danish Siddiqui/File Photo