The West celebrated in 1989 as the Berlin Wall came down and again in 1991 as the Soviet Union dissolved—and the formerly “captive nations” of Central and Eastern Europe liberated themselves from communism and Soviet domination. Central Europe and the Baltic states acted decisively during this historic window of opportunity. They anchored themselves not only in the West, but in its institutions of NATO and the European Union (EU).

The path has been more difficult for Europe’s east.

In 2008, as we debated the aspirations of Georgians and Ukrainians at NATO’s Bucharest Summit, we witnessed that historic window of opportunity come slamming shut. In the face of Russian hostility, Georgia’s and Ukraine’s uneven progress, and the West’s ambivalence, NATO failed to reach consensus. Allies did not extend Membership Action Plans to help Georgia and Ukraine prepare for membership. They did agree, however, that the two aspirants would one day become members of NATO. The indecision among allies in Bucharest led to decisive action by NATO’s by then self-declared adversary in Moscow: the war in Georgia in 2008.

In the wake of this crisis, the United States and NATO stepped back, and the EU stepped forward with its Eastern Partnership. Underestimated by Moscow at first, Russian President Vladimir Putin soon concluded that he had to stop the EU’s initiative as well.

The EU’s offers of political affiliation through association agreements, economic integration through deep and comprehensive trade agreements, and elimination of barriers to travel through visa liberalization polices were the ingredients to accelerate the adoption of European norms and values in post-Soviet nations. They created the conditions in which individual choices could shape a country’s strategic orientation.

Putin coerced Armenia to stop this process. He tried to stop Moldova. His efforts to coerce Ukraine produced the Revolution of Dignity, which the Kremlin responded to by illegally annexing Crimea in 2014, and invading Donbass.

Today, in 2018, the Kremlin seeks even more: to roll back decades of gains in Central Europe and to prevent such advances in Europe’s east. Moscow’s efforts to undermine democratic institutions, propagate disinformation, and wield corrupt influence aim to restore its influence in Central Europe, splinter NATO and the EU, block their expansion east, and undermine the sovereignty of nations in Europe’s east. Indeed, Russia aims to establish a permanent grey zone between itself and NATO and the EU. But Moscow is learning that the people of the region have a say—and they won’t have it.

The West owes to it those struggling for their own nationhood and freedom to choose their destiny, to recognize that this region is no grey zone. It is, in fact, the frontline of freedom and it merits our support.

Permitting these nations’ aspirations to be held hostage by Russian occupation and intimidation is a recipe for instability and conflict in Europe. We cannot allow these nations, known as “captive nations” for much of the 20th century, to become known as the hostage nations of the 21st century.

This is not only a just cause, but also in our own interests because welcoming the aspirations of those in Europe’s east is the best path to stability and peace.

In 1959, thanks in large part to Lev Dobriansky (the father of Atlantic Council Executive Committee Board Director Paula Dobriansky), the US Congress and President Dwight D. Eisenhower declared a “captive nations” week to bring attention to the struggle of these countries. The “captive nations” resolution provided a rallying cry, a narrative, and a forum that focused on the liberation of states dominated by communism and stigmatized Moscow’s egregious behavior. The resolution rallied Americans behind a moral cause, produced a common front, and gave agency to the nations concerned—after all, they were their own nations, but captive. This initiative continues today.

Informed by this legacy, we must understand the threat to nations in Europe’s east as a common challenge—one of ensuring their nationhood.

The reality in many of the nations of Europe’s east is messy. We cannot and should not defend every decision they take or every leader they choose. At the same time, we must protect the ability of these nations to be sovereign, whole, and free, with their own identity and free to choose their own destiny.

These ideas may seem counterintuitive at a time of transatlantic divisions and heightened tension with Russia. Yet a big transatlantic project such as this could help secure the Alliance and anchor others, such as Turkey, more firmly in the West.

It would also provide Russia a more predictable set of neighbors and would remove the grey zones that tempt its revanchist behavior.

This strategy is not meant to create a new dividing line in Europe. The aim is to anchor a vulnerable and insecure zone in the certainty of a stable, prosperous, and free Europe. Over the long term, this vision should include a future democratic Russia. But the pathway to reform must begin with choices in Kyiv, Chisinau, Yerevan, and Tbilisi.

Damon Wilson is executive vice president for programs and strategy at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DamonMacWilson.

This post is an abridged version of remarks given at the Atlantic Council’s conference, Championing the Frontlines of Freedom: Erasing the ‘Grey Zone.’ Full video of the conference can be found here.

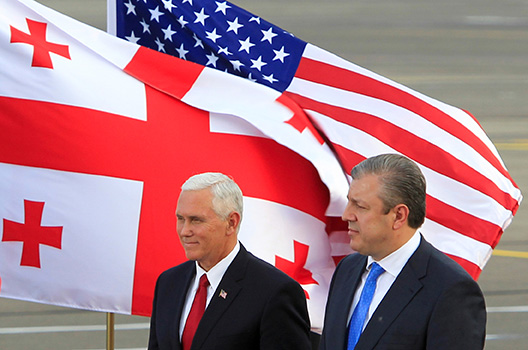

Image: U.S. Vice President Mike Pence and Georgian Prime Minister Georgy Kvirikashvili attend a welcoming ceremony at the Tbilisi International Airport, Georgia July 31, 2017. (REUTERS/Shakh Aivazov/Pool)