In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Chilean President Sebastián Piñera moved quickly to stockpile medical supplies. But the country took its biggest risk in April 2020—investing serious financial resources in deals with a number of companies developing vaccines at an uncertain time, ensuring that Chile would have the vaccine supply it needed at a fair price down the line.

“We decided that we were willing to risk money, but we weren’t willing to risk lives. That was our philosophy,” Piñera said Wednesday, at the annual conference hosted by the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center alongside the United Nations General Assembly.

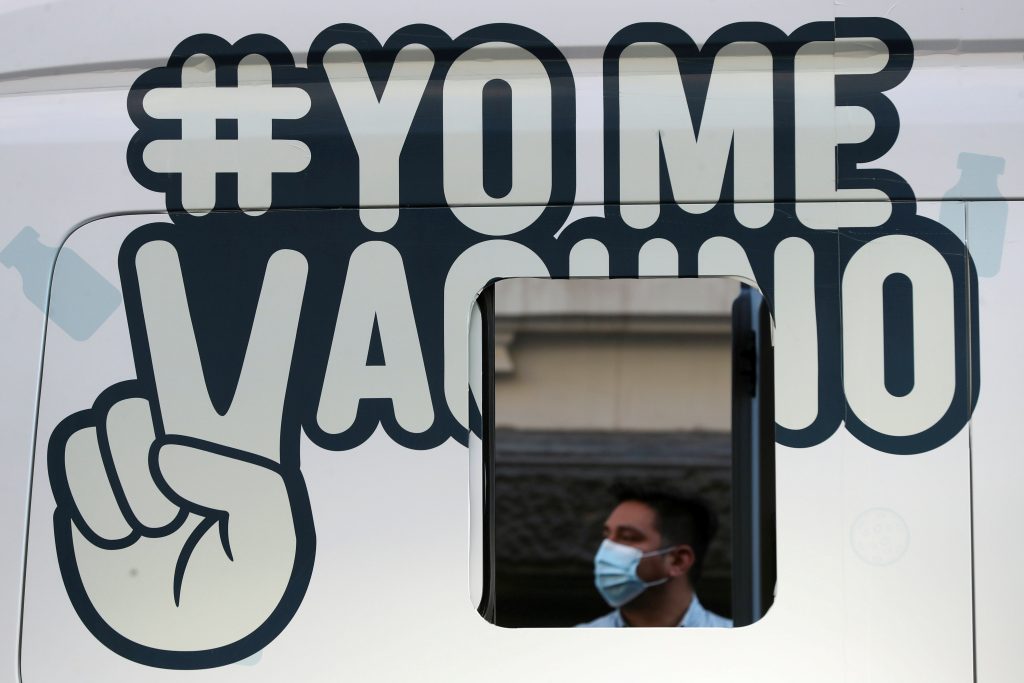

Now Chile is known as the vaccination champion of Latin America—leading the region (alongside Uruguay) after having vaccinated 72 percent of its population with two doses and about 30 percent with a third dose amid the rise of the delta variant of the virus.

The region is still reeling from the pandemic: Latin America makes up 8 percent of the global population, yet accounts for 21 percent of COVID cases and 30 percent of deaths. As regional leaders came together at Wednesday’s conference to outline a path toward a health and economic recovery—while showing how the fate of Latin America and the Caribbean has far-reaching ramifications for the world—Piñera saw hope in this solidarity for solving any number of global challenges, from strengthening democracies to addressing income inequality and tackling climate change. “Despite all the problems,” Piñera said in the conference’s keynote address, “the best is yet to come.”

Read more of the most valuable insights from the discussion below.

Fighting for equity and health

- Costa Rican Vice President Epsy Campbell-Barr reported widespread, equitable distribution of diagnostic tests and vaccinations regardless of class in her country. However, she has seen limited effects from the COVID-19 technology access portal—the “CTAP” effort backed by forty nations and the World Health Organization meant to spread the vaccine more equitably across the world—because large countries and major pharmaceutical companies hadn’t joined while trying to protect trade secrets and patent exclusivity rights. “It is insufficient if we feel we can work only with countries who have more money, and leave behind the countries that are the poorest in the world,” Campbell-Barr said.

- Without a more equitable approach, the world will find it difficult to leave the COVID-19 pandemic behind, said Carla Vizzotti, Argentina’s minister of health, which has enough vaccines through current agreements to inoculate 69 percent of its population and is currently experiencing some of its lowest COVID-19 case and death rates since summer 2020. She warned that an uneven re-opening of economies would only exacerbate long-term inequalities between Latin America and other regions, calling for more direct donations of vaccines from wealthy nations. “The reality is that the access to vaccines has not been equal,” she said.

- Campbell-Barr also highlighted the challenges in vaccinating migrant populations. Their quality of medical care has been impossible to track, because Costa Rica doesn’t currently log their immigration status when administering vaccines. Plus, they face many of the prejudices asylum-seekers face worldwide—including erroneous accusations that they are responsible for spreading disease, taking jobs, and increasing crime. “It is essential to have data on the number of migrants, as well as their epidemiological profiles,” Campbell-Barr said, while urging other nations to fight the politicization and stereotyping of asylum-seekers.

Watch the full event

How the comeback takes off

- Expect to hear a lot about near-shoring in the near future, with deep ramifications for both Latin America and the United States. The pandemic exposed weaknesses in global supply chains, versus commerce relying on sources closer to home. “We see Europe; they’re integrated. We see Asia integrated. We don’t see Latin America very integrated,” said José Varela, president of 3M Mexico. “Many companies are looking to invest closer to the US.… Latin America and the Caribbean are well-positioned to take advantage of this opportunity,” added Carlos Felipe Jaramillo, who is the World Bank’s vice president for the region.

- The pandemic also underscored the importance of trade agreements in national security, as the disruption of global trade suddenly presented a major threat to domestic health in many parts of the world. “Without access to vaccine imports, additional doses wouldn’t be possible” for many countries, said Anabel González, deputy director-general for the World Trade Organization. That has led to key adjustments in Latin American nations, González said—including reforming export restrictions and encouraging greater voluntary licensing and technology transfers—as well as ambitious policy reform around biodiversity in Costa Rica and green jobs in Ecuador. Despite early setbacks during the pandemic, she said that Latin America and the Caribbean has much to offer and can set an example in numerous areas for the accelerating global recovery.

- All three economic experts agreed that the past year has greatly accelerated digital adoption in Latin America, where only about half of the population has consistent internet access. “There is a huge business opportunity for those interested in this growing market, at a time where governments have realized the importance of connecting people to digital tools—and are willing to pay some of the costs of the last mile of incorporating rural, poor populations in this ongoing digital revolution,” Jaramillo said. Latin America can build on that progress by tackling longstanding barriers, González said, such as cumbersome regulations.

The Chilean example

- Chile is continuing its aggressive inoculation plan, now vaccinating children 6 years old and up with the Chinese Sinovac vaccine, with plans to soon start vaccinating kids as young as 3. “You cannot avoid the virus entering the country. The only thing we can ensure is that we are well-prepared for when that happens,” said Piñera, who credited his country’s high vaccination rates for mitigating the damage of the delta strain.

- Throughout his address, Piñera emphasized his trust in the science behind the vaccine—while underscoring his disappointment in many global leaders. “This pandemic has been a huge success of science and a great failure of politics,” Piñera said. “The citizens are asking us political leaders to act, and they are asking that as a moral imperative.” Piñera said that Chile has tried to lead by example, donating vaccines to countries in greater need, even as supplies were scarce: “Solidarity is very important.”

- Piñera directly tied trust in the science behind the vaccine to trust in the science behind another great global threat—climate change. “The science has spoken loud and clear,” Piñera said. “Technology gives us the tools and instruments to change the course of history. Now it is our responsibility to take the climate change threat seriously… otherwise, nobody will forgive us.”

Nick Fouriezos is an Atlanta-based writer with bylines from every US state and six continents. Follow him on Twitter @nick4iezos.

Further reading

Image: A man waits outside a mobile vaccination center to receive a dose of Sinovac's CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccine in Santiago, Chile, on May 24, 2021. The sign reads ''I get vaccinated." Photo by Ivan Alvarado/Reuters.