The high-altitude Chinese balloons that violated US airspace have drawn new attention to Beijing’s increased brazenness abroad. Much of the world is watching with scrutiny for what might float out of China next. But fewer people took note last week of what, or rather who, flew into China.

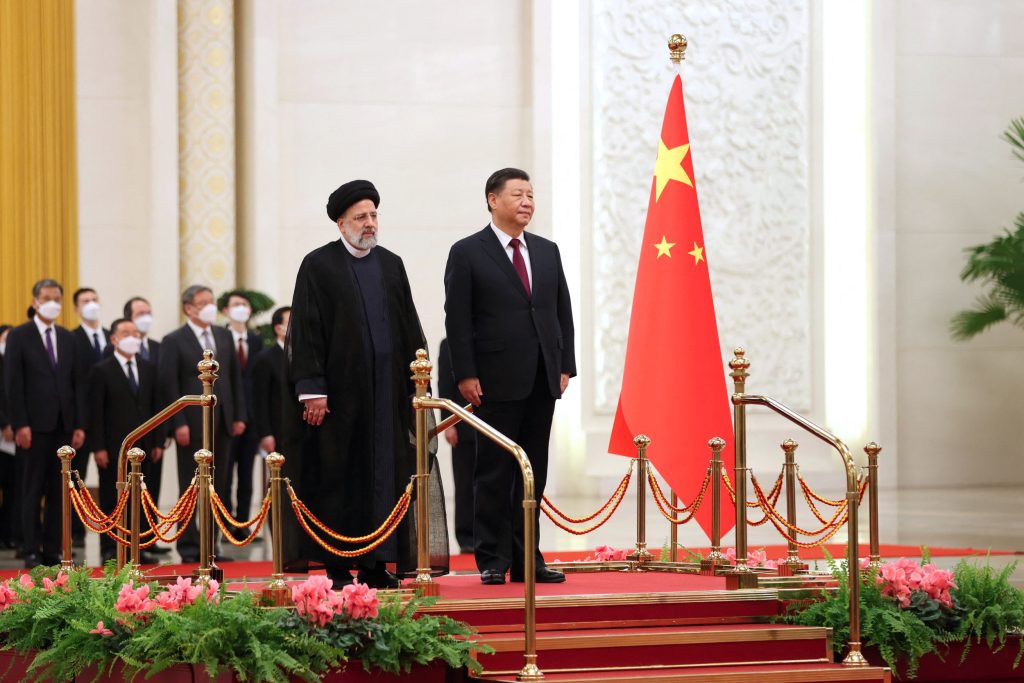

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi visited Chinese leader Xi Jinping in Beijing last week. At the conclusion of the three-day trip, Xi accepted Raisi’s invitation for a visit to Iran in the future. This comes after Xi traveled to Saudi Arabia and met with Gulf leaders in December. Below, Atlantic Council experts shed light on how China is reaching out to the Middle East and what Iran, in particular, wants from Beijing.

1. What was China’s aim in hosting such a high-profile visit from the Iranian president?

I suspect a part of this reception is relationship repair after Xi’s visit to Riyadh in December. When he last visited Saudi Arabia in 2016 he stopped in Iran on the way home. This time not only was there no Iran visit, but the joint communique of the China-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) summit featured language that indicated Beijing’s support for the United Arab Emirates’ position in its long-standing dispute with Iran over the Greater and Lesser Tunbs and Abu Mousa (islands near the Strait of Hormuz). This resulted in a lot of angry commentary from Iranians who questioned China’s commitment to the country and the government’s ability to manage its most important bilateral relationship. Raisi’s visit likely is a means of restoring a bit of balance to China’s presence in the Gulf.

—Jonathan Fulton is a nonresident senior fellow in the Middle East Programs and the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council and an assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi.

2. This month marks forty-four years since the Islamic Revolution in Iran, and anti-government protests are continuing in the country. What message does the Iranian president’s visit to China send to Iranians?

Raisi’s China visit was his first international visit since demonstrations ramped up while he was at the United Nations General Assembly in September, apart from an overnight trip to Astana, Kazakhstan, in October. The message the regime intends to send to Iranians from the visit is likely to be that the Islamic Republic remains in sufficiently firm control for the president to go traveling and that it retains powerful international friends in better odor than Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

In the context of the demonstrations, the visit may also be intended to send the message that the regime is seeking to reduce the economic pressure on ordinary Iranians in pursuing the potential economic benefits of the 2021 strategic partnership agreement. However, this will be mitigated by the fact that economic engagement with China has not delivered to date and never been popular, and the regime will be seen as playing catch-up in relations with China following Xi’s recent visit to Saudi Arabia.

Finally, it is unlikely to be lost on Iranians that the regime has expressed admiration for the Chinese model of social control, particularly of the internet, which it would emulate if it could.

—Paul Foley is an advisor to the Atlantic Council’s Iran Strategy Project and a former ambassador of Australia to the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Raisi’s trip to Beijing is likely meant to show Iranians that their country is not as isolated as it appears. Despite protests and an economy devastated by sanctions, the Islamic Republic still has a great-power partner it can rely on. For China, however, this message may not be especially helpful over the longer arc. It is clear that Iranians do not support their government, and there is already deep popular resentment of China. The perception of Beijing propping up a government that nobody likes will only add to negative impressions of the People’s Republic of China.

—Jonathan Fulton

3. Does China’s conspicuous befriending of Iran factor into its relations with other Middle Eastern countries, such as Saudi Arabia?

In the ideal world that Chinese policymakers envision, their country is uniquely positioned to accomplish the impossible: increasing its influence and presence in the Middle East without becoming embroiled in its endless conflicts. Needless to say, our world is far from ideal. While China’s engagement in the Middle East has increased across the board over the last decade, maintaining an aloof and neutral stance has proven more difficult.

For one thing, China’s vested interests have increased in tandem with the need to protect them. For another, Beijing is also observing how the United States has been pressuring its regional allies and partners to restrict their cooperation with its main “strategic rival.” This corresponds to Xi’s growing ambition to challenge US hegemony and promote the superiority of the “China Model,” which includes a “new security architecture for the Middle East,” as detailed in my recent issue brief for the Atlantic Council.

Furthermore, Iran’s adversaries see every dollar China spends on Iranian oil as another dollar for the self-proclaimed revolutionary regime to spread its terror and extremism. Iran, for its part, was incensed by Xi’s December visit to Riyadh and the resulting eye-watering memoranda of understanding and joint statements with its Gulf rivals that named and shamed it. Consequently, Beijing has taken a slew of steps since December to assuage Tehran’s concerns, the most recent of which was Raisi’s exceptionally cordial visit.

Lastly, if China threw Iran under the bus in the first joint statement, now it was Israel’s turn. Not only has the China-Iran statement whitewashed the terrorist activities and nuclear blackmail of the ayatollahs’ regime, but it also specifically pointed a finger at Israel. Clearly, China tells everyone exactly what they want to hear. In its view, this is the ideal manifestation of its “balanced” and “friendly” diplomacy. In practice, this makes it an unreliable partner, because when everyone is your friend, no one is.

—Tuvia Gering is a nonresident fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub and a researcher with the Diane and Guilford Glazer Israel-China Policy Center at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) in Tel Aviv.

4. Is a “triple axis” of China, Iran, and Russia emerging, in which all three work in closer coordination against the West?

The Iranian regime would certainly favor the emergence of such a “triple axis” to reduce its international isolation, to undermine international will to take action against Iran on its behavior through bilateral and multilateral sanction regimes, and as a fallback in handling the nuclear file. The regime would also approve of what its leaders would see as Iran’s rightful place at the civilizational top table of such an axis.

While Iran and Russia are working in close cooperation on Ukraine and, to some extent, Syria, their interests may not align on the nuclear file. Moreover, it is not obvious that China would be keen for such close identification on contentious issues. Therefore, beyond a shared desire to undermine the international order shaped by Western norms, any emerging “triple axis” may well prove to be issue-dependent.

—Paul Foley

Further reading

Wed, Feb 15, 2023

What US adversaries are learning from the balloon and UFO saga

New Atlanticist By Jennifer A. Counter

The reactions to these objects among politicians and the public say more about "us" than "them."

Tue, Feb 14, 2023

China’s balloon blunder shows the shortcomings of its national security apparatus

New Atlanticist By Mark Parker Young

The composition of China's security structures indicates that the military did not want to disrupt a major diplomatic moment and thought the balloon would be undetected.

Wed, Feb 15, 2023

Full throttle in neutral: China’s new security architecture for the Middle East

Issue Brief By Tuvia Gering

This report addresses two widely held beliefs about the nature of China’s engagement in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) that ought to be revisited in light of notable developments. First, while it is widely assumed that Beijing’s interests in the region are limited to energy security and economic ties, this report will show how cooperation has […]

Image: Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi stands next to Chinese President Xi Jinping during a welcoming ceremony in Beijing, China, February 14, 2023.