World leaders arrived in Beijing on November 10 for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit meeting, as China seeks to emphasize its global economic influence and power. Yet, even while China demonstrates its economic might, the country’s slow response to the Ebola crisis in West Africa – where it has a substantial commercial footprint — raised questions about China’s leadership role beyond the economic sphere.

World leaders arrived in Beijing on November 10 for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit meeting, as China seeks to emphasize its global economic influence and power. Yet, even while China demonstrates its economic might, the country’s slow response to the Ebola crisis in West Africa – where it has a substantial commercial footprint — raised questions about China’s leadership role beyond the economic sphere.

Indeed, bilateral trade between China and the three most affected countries – Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea – is estimated around $5.1 billion.

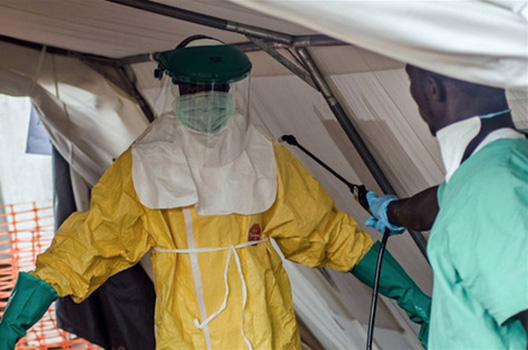

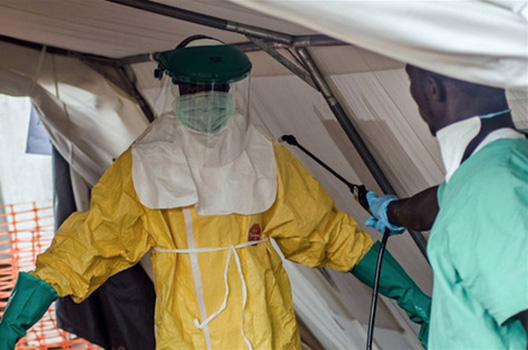

As the Ebola outbreak became more global in nature, the world community started coming together to develop a coordinated response. China, on the other hand, continued to provide aid to a select few West African nations in its typical bilateral fashion with little regard for the nature of the health crisis.

Last week, however, acceding to international criticism, the Chinese government announced it is sending “an elite unit of the People’s Liberation Army to help Ebola-hit Liberia.”

This may be a sign that China is beginning to recognize that its traditional approach to foreign aid in Africa is not only insufficient in the current crisis, but may have long-term adverse consequences in terms of African goodwill toward China.

China has significant economic interests in West Africa, as well as tens of thousands of Chinese citizens working and living in the region most affected by the current Ebola outbreak. Yet its response to the crisis so far, compared to that of other nations such as the US, the UK, and even Cuba, has been significantly below par and recently opened it up to criticism by Western governments, as well as the United Nations. Late last month, China’s Premier, Le Keqiang, responded defensively to these criticisms by announcing an aid package for West Africa of approximately $16.3 million, in addition to the team of nearly 200 medical personnel dispatched to Sierra Leone in September, and previous aid donations of approximately $38 million.

In comparison, Cuba has dispatched, or is planning to dispatch, more than 400 healthcare workers to Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia, and has offered to collaborate with the United States on containing the outbreak.

A few U.S. officials anonymously sniped at the Chinese response, observing that aid flowed mostly to Sierra Leone, where China has significant diamond mining interests. Taking a more generous stance, a Council on Foreign Relations brief makes the point that China’s approach to healthcare and other aid takes a longer, more strategic view than Western nations with a ‘horizontal’ approach that focuses “on prevention and care for prevailing health problems.”2 This contrasts with ‘vertical’ systems more familiar to Western democracies that target a specific health threat without necessarily being integrated into existing local health systems.

Whether or not the criticisms are valid, China may be slowly catching on to an important point. The Ebola epidemic has taken on global proportions, with public fears driving governments to radical measures that could impact China’s economic interests in West Africa. The disease on has led to the collapse of the already insufficient health care network in Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea. As the UN argues, the solution requires a coordinated, system-wide approach to address the disease at its source.

Both in its own economic self-interest and, arguably, the enhanced public relations benefit that may accrue, China should align its relief efforts with those of the other key international organizations and nations. For starters, Chinese investment to build resilient healthcare institutions on a scale much broader than merely in Freetown, Sierra Leone would be a valuable contribution to the problem in line with its preferred horizontal approach.

Africans have long memories and will remember who their friends were during this moment of desperate need. The deployment of the People’s Liberation Army hospital unit may be a sign that the Chinese government is beginning to understand the stakes – and the cost of inaction.

Chris Leins is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center. He retired from the US Army in April 2014 with the rank of major general after thirty-five years of service. In his last four years in the military, he served as director of politico-military affairs (Africa) on the Joint Staff.