Click on the banner above to explore the Tiger Project.

MANILA—There’s an overall sense of optimism these days in the Philippines’ capital city, but it’s mixed with foreboding. In our recent week of meetings with a range of Filipino, US, and other like-minded government officials, military officers, and outside experts, the threat from China to the Philippines’ sovereignty and self-determination was palpable in almost every conversation.

Upon our arrival, local media outlets were highlighting the ninth anniversary of the arbitral tribunal ruling that found China in gross violation of international law in Philippine waters. Though the ruling was a moral and legal victory highlighting international support for the Philippines, it also revealed the limits of that support. In the years since, China’s violations have escalated.

Clearly, the Philippines needs more international help, and it has sought such assistance by documenting and publicizing aggressive Chinese actions. Interestingly, as the Philippines has focused more on Chinese threats to itself, Manila also seems increasingly inclined to see its own security as connected to that of the broader region, including Taiwan.

This week, President Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines was in Washington for meetings on trade, security, and defense issues with US President Donald Trump and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth. These meetings advanced US-Philippines defense cooperation on several fronts, with China the largely unspoken target. But more attention is needed on the threats emanating from Beijing. The more domestic and international transparency about the regional threats posed by China, and the more evidence of the need to work together to face them, the stronger and more unified the United States and its friends and allies in the region are likely to be.

“They’re already here!”

During our visit, we spoke with many experts and officials, and our conversations were largely conducted under the Chatham House rule, so what was said could not be attributed to individual speakers. But a common theme in many of our discussions was that China is escalating its coercive pressure and subversion against the Philippines. As one US official said of China’s pressure in the area: “They’re already here!” The US Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) characterizes the situation as a “war without gunsmoke,” where China’s maritime forces steadily reshape the status quo short of open conflict.

This threat is also evolving. In our discussions with Philippine Coast Guard leadership and Manila-based security scholars, a “significant uptick” was noted this year in the deployment of People’s Republic of China (PRC) research and surveillance vessels deploying remotely operated vehicles across the broader South China Sea. Simultaneously, there has been a surge in Chinese maritime militia activity—coercive state actions deliberately masked as civilian maritime traffic.

Meanwhile, China’s influence in the Philippines, including Chinese Communist Party subversion and “elite capture,” was also at the forefront. One recurring question in Manila was: “How many Alice Guos are still out there?” This is a reference to former Mayor Alice Guo, an accused Chinese spy, who a local court recently found guilty of hiding her identity as a Chinese citizen. Though popular sentiment in the Philippines runs against China in polls, pro-Beijing politicians are still influential, and some are still winning elections. One Filipino expert reminded us that, just like in most democracies in peacetime, the average voter is more concerned about the economic and social matters of daily life than international threats, helping to explain the apparent disconnect.

Another local expert noted that Filipinos may perceive the threat from China as serious but not existential. China’s goal is not to occupy the Philippines, the expert said, just to dominate Manila’s decision-making to the point that it cannot take actions Beijing does not approve of, such as supporting Taiwan if it comes under attack from China.

Welcome to the “one theater” in the Western Pacific

It looks like China’s efforts to pressure the Philippines have backfired. Earlier this month, Secretary of National Defense Gilberto Teodoro embraced the “one theater” concept, described by one media outlet as referring to “the South China Sea, East China Sea, and the Korean Peninsula as a single and integrated theater of operations in wartime.” In his comments Teodoro had a slightly narrower take, focused on the maritime aspect and noting that the Korean Peninsula should not be included, despite South Korea, like Australia, apparently being one of the like-minded countries sought for involvement.

The “one theater” concept is a major step forward in thinking about defense, though admittedly it is still in its early stages of implementation. Teodoro noted the goal of “synergy in operations, domain awareness, intelligence exchange, and mutual reinforcement,” which would likely face operational challenges to realize.

Another obstacle in realizing this vision may be in ensuring the necessary international and public support. This “one theater” concept was put forward by Japanese Defense Minister Gen Nakatani, and Hegseth has reportedly welcomed it. It seems taken as a given that Canberra would be on board, but some we spoke to in Manila pointedly asked about South Korea—where there has already been some opposition to the idea in the media. Despite a growing awareness of the potential of having to face simultaneous threats from China and North Korea, and some South Korean experts openly assessing what its role could be, Seoul has been reluctant to even discuss the possibility of its involvement in a regional conflict.

Meanwhile, despite facing a growing challenge of their own from Chinese maritime incursions, South Koreans seem reluctant to openly confront China or see this as linked to the maritime incursions others are facing. Manila has a far more willing partner in Taipei for security cooperation to face the challenge from China, as the Washington Post reported and as we heard in our discussions with Taiwan’s officials in Manila. But experts we spoke with noted Manila’s hesitancy to openly align with Taiwan, both due to domestic critics and the potential for backlash from Beijing.

Transparency is controversial but critical

A key advantage for Beijing in its campaign of expansionist coercion has been what CMSI calls “foreign difficulty in understanding the situation, let alone determining an effective response.” However, since 2023, no country has done more to narrow this understanding gap than the Philippines. Alongside assertive operational efforts to defend its maritime rights, the Philippine government has adopted a strategy of assertive transparency, leveraging embedded international media to expose Chinese activities and shape global perception.

We found that this policy of assertive transparency remains a contentious subject in some circles in Manila, despite being the president’s policy and apparently enjoying widespread public support. One expert we spoke with suggested that repeatedly broadcasting details of China’s aggression without proportional counteraction showed weakness, or at best a sense of futility. Others even suggested that transparency about confrontations at sea with Chinese vessels could unintentionally arm critics in the Philippines to stoke fears in the population that calling out China’s behavior will provoke, rather than deter, Beijing. However, the majority of those we spoke with saw more advantage than disadvantage in the policy.

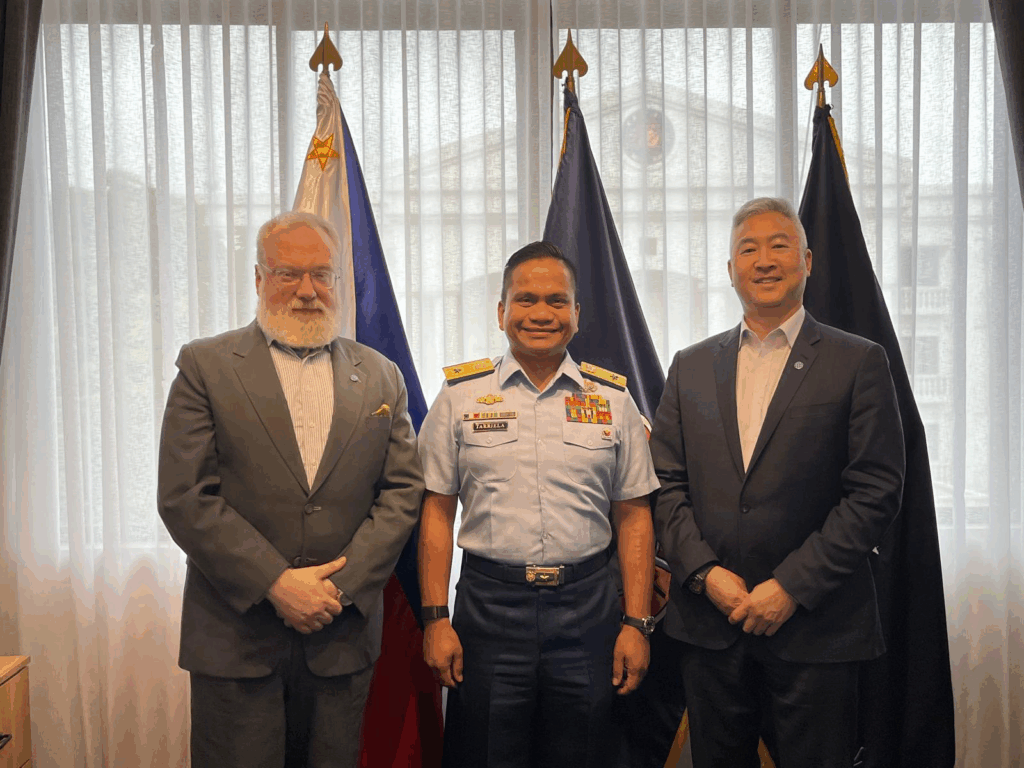

Perhaps no individual is more publicly associated with such transparency than Philippine Coast Guard Commodore Jay Tarriela of Manila’s West Philippine Sea transparency group. In his discussions with us, he highlighted the strategic benefits of the policy, noting: “The greatest impact of the transparency effort is that we were able to convince the international community and those who support the rules-based order that [ours] is not just a fight for us for our sovereignty but it is a fight for every nation who believes in the adherence to international law . . .”

We agree with the commodore—though we do think much more remains to be done. As China applies similar ICAD (Illegal, Coercive, Aggressive, and Deceptive) tactics in the waters around Taiwan and, increasingly, in the Yellow Sea near South Korea, the Philippines’ transparency-driven approach offers a useful model. By publicizing these ICAD or “gray zone” activities in real time and enlisting international attention, Washington, Seoul, Taipei, and other capitals can enhance maritime domain awareness, counter cognitive manipulation, and complicate Beijing’s efforts to operate aggressively below the threshold of open conflict.

Tarriela assessed that China had changed its maritime tactics in several ways since the Philippines began its assertive transparency campaign in 2023. He had several theories as to why this was the case, but it is hard to know what effect it has had on Beijing’s strategic calculus. Ultimately, whether authoritarian adversaries are deterred by transparency about the nature of their activities, the real audiences are in societies that enjoy freedom of the press. The people of these free countries must come to understand the common threats that they face in the Indo-Pacific. Only then will a unified, strong approach to these threats emerge.

Right now, Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un are increasingly aligned, while their institutions and people are internally in lockstep behind whatever aggressive policies they put forth. In response, regional allies and partners must stand together. To begin with, the United States, Australia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan should follow the example of the Philippines and more clearly call out the nature of the PRC’s behavior. Moreover, they should do so while working together to operationalize a “one theater” approach to countering this aggression and deterring potential simultaneous threats.

The Philippines is the least wealthy and least well-armed of this group by an order of magnitude, and it is battered by direct acts of violence from the PRC on a near-daily basis, yet it is not afraid to stand up. The rest of us have no excuse, and there is no time to waste.

Markus Garlauskas is the director of the Indo-Pacific Security Initiative at the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and the leader of the Council’s Tiger Project on War and Deterrence in the Indo-Pacific. He is a former senior US government official with two decades of service as an intelligence officer and strategist, including twelve years stationed overseas in the region. He posts as @Mister_G_2 on X.

Rear Admiral Philip Yu (US Navy, retired) is a nonresident senior fellow with the Indo-Pacific Security Initiative. As a Navy foreign area officer with a background in nuclear submarines, he served in multiple assignments requiring direct interactions with Chinese military counterparts, and his final military assignment was as the US defense attache in Moscow during the lead-up and start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The authors’ travel to Manila was made possible by a partnership with CRDF Global, an Arlington, Virginia-based non-profit, for a project sponsored by the Canadian government’s Global Affairs Canada. The meetings that informed this analysis were conducted at the Atlantic Council’s expense. The views expressed here are the authors’ own.

Further reading

Tue, Aug 13, 2024

From the Pentagon to the Philippines, integrating deterrence in the Indo-Pacific

New Atlanticist By Kevin M. Wheeler

The United States and its Indo-Pacific allies must work together across all levels and domains for their regional deterrence to be effective.

Thu, Sep 12, 2024

Dispatch from Manila: On the frontlines of the ‘gray zone’ conflict with China

New Atlanticist By Markus Garlauskas

In the Philippines, China’s aggression is not in some shadowy, ill-defined “gray zone.” It’s a real and constant series of attacks on the country’s people and sovereignty.

Wed, Nov 22, 2023

China’s acoustic aggression against a US ally follows a pattern. Military talks won’t help.

New Atlanticist By Markus Garlauskas, Philip W. Yu

On November 14, a Chinese warship used its active sonar to harass and injure two Australian Royal Navy divers with high-powered sound waves.

Image: Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth welcomes Philippine President Ferdinand "Bongbong" Romualdez Marcos, Jr. to the Pentagon, Washington, D.C., July 21, 2025. (DoD photo by U.S. Navy Petty Officer 1st Class Alexander Kubitza)