Why all the Germany bashing? There’s no “France bashing,” “Britain bashing,” or “Poland bashing” when it comes to foreign and security policy. Why is it that these countries can still live in their historical stereotypes of grand, global, and aggrieved without being subject to the same highly critical treatment as the Germans? Of all Western countries, Germany has perhaps moved furthest since February last year, and yet it receives the harshest hearing.

Clearly there are legitimate criticisms, and these should not be dismissed as unfair bashing. Despite the progress made, Germany has struggled—even from a low baseline—to move far enough or fast enough on key issues, including advancing NATO membership for Ukraine, properly arming its military, and confronting the threat from China. But the truth is that Germany’s transformation is becoming a problem of form as much as content.

The reason that Germany does not get to live in a cozy stereotype is because there isn’t one. Its allies may see Germany moving, but they have little sense of what to expect from Berlin, let alone how to influence it strategically. Amid mutual misperception and communication failures, legitimate criticism can tip into bashing. To curb such criticism, Germany needs to re-establish its foreign policy identity in a way that serves its interests and that its partners accept.

This will be a challenge, but it should not be seen as a threat. Rather, it gives the current political generation a great opportunity to reinvent Germany’s position, enhance its power, and renew its purpose as an international actor—if German politicians embrace greater self-awareness and awareness of others (especially allies), and if they ditch exceptionalist views of leadership.

Time for a new stereotype

Allies rightly demand change in response to geopolitical shifts, but they also crave predictability and a sense of who fits where—especially from such an important player in Europe as Germany. With German policy and posture in flux, its partners simply do not know what to expect, so they throw their own labels at it. They want an accurate new German stereotype, a social shorthand.

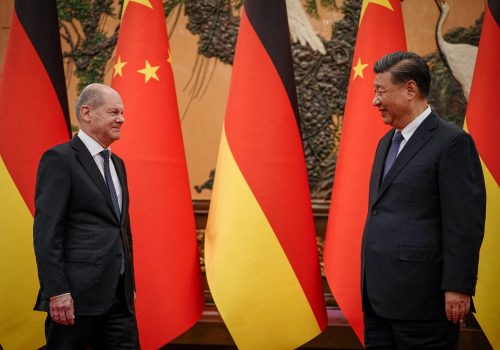

Chancellor Olaf Scholz has resorted to “thoughtful and reliable,” claiming to think things through from a whole-Alliance perspective then triple checking that it can really deliver. Following a long strategic rethink, he has erred on the side of caution even on key points such as readiness to meet the NATO target of spending 2 percent of gross domestic product on defense, which has become even more necessary since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

This is good old German branding that Scholz thinks plays well at home. Yet, predictably, this bid to reset Germany’s identity is not sticking with allies. It irritates those who understand that the cost of slow deliberation and cautious calibration is measured in Ukrainian lives and weakened European deterrence. They believe “thoughtful and reliable” is little more than “fretful and reluctant to move with the demands of the times.”

Scholz’s failure to appeal to allies has made him a particular object of Germany bashing. If he genuinely thought things through for the whole Alliance, then he would understand and to a degree internalize the views of partners—and sometimes move at their pace. His self-satisfaction exemplifies how this political generation in Berlin risks losing its chance to set the next German stereotype.

Die Mannschaft

Germany has successfully reinvented itself before. Now it needs to produce a stereotype that addresses allies’ concerns, plays to Germany’s strengths, and represents something Germans can get behind. So why not die Mannschaft (the team)—or more precisely “team-play”—as showcased in Germany’s celebrated ability to get its soccer players to work together and become far more than the sum of their parts.

Team-play can be readily applied to Europe’s alliances and international partnerships. At a basic level, this is simply about each country recognizing that the team needs it and it needs the team—which leaves no room for indulging in narcissistic domestic debates. For the Scholz government, it means not measuring its contribution in terms of its readiness to break domestic taboos, but instead in responding to real-world needs and allies’ concerns.

Look at how the Dutch stepped up when they became aware that Europe needed a different kind of contribution from them. In 2020, their assessment of their place on the European team changed, and so too did their diplomatic approach. Britain had just left the European Union (EU), and decisionmakers in The Hague perceived that the Netherlands was no longer the biggest of the small EU states. It was now, instead, the smallest of the big states.

Germany would win points by signaling that it will be a team player in the same way as the Netherlands. Realizing what was required of them, the Dutch stopped seizing on single issues and trying to build blocking coalitions; they began covering the full range of European affairs and building productive coalitions. As their status grew, they replaced political self-indulgence with self-discipline—and greater influence.

‘Team power’ helps others shine

Team-play is not just about being aware of how you relate to others, but how they relate to you—harnessing their relative strengths and covering for their weaknesses. This notion of “team power” is one that EU and NATO officials now apply to the Euro-Atlantic community, as they try to move beyond technical conversations around mutual obligations and interoperability—and they expect Germany to be a linchpin of it.

Germany’s teammates are already pulling together in this spirit. For example, Estonia doubled down on liberal values and increased defense spending in order to better face the authoritarian challenge to its east. Even France is recognizing that it needs to play differently, especially alongside Central and East European states if it is to exercise leadership within, rather than in competition to, NATO.

Germany, by contrast, reassures itself by pointing to the failures of others. It belittles Poland’s inability to provide positive ideas for the future of Europe, while ignoring its massive military capability upgrades. It scorns French efforts to build credible alliances in Central and Eastern Europe, while failing to see how useful this might be. And it reassures itself that the United Kingdom is overstretching itself militarily in Ukraine, instead of plugging into British initiatives.

A sensitive team player would step in and offer face-saving support that would serve the team’s interests. France and Britain, for instance, are proposing ambitious ideas for European defense not (only) due to ingrained delusions of grandeur which Berlin imputes. Paris and London have started to rein in their hubris and they have sensible aims—to show to the Americans (and Russians) that Europeans can lead on European security. But to do this, they need the Germans.

Germany is not simply entitled to be team captain

Many Germans would say that they already anchor the team as the inevitable European captain. This is a bad misreading of the situation. It is true that Germany will always have a crucial role—thanks to its size, geography, and wealth. But this does not make it Europe’s leader nor a team player.

France, Poland, and the United Kingdom know this. Their heavy scrutiny of Germany reflects a desire for Berlin to perform and be seen to perform better. They know what an asset a fully team-playing Germany would be for European security. This goodwill tips into bashing for the same reason: They know that if Germany fails to deliver, it is Europe that will suffer.

These countries appear to worry, moreover, that Germany has not even noticed that it is a standard-bearer of the European team. Germany comes to the pitch with a sense of entitlement and an assumption that it can talk eye to eye with US President Joe Biden. Worse still, Germany hides behind the United States on defense and Alliance politics. It fails to better coordinate with European partners, sticking rigidly to its own—often flawed—conception of its interests.

Overall, this makes Europeans more, not less, beholden to the United States. It frustrates their efforts to take greater charge of their security and fails to address Washington’s concerns over burden sharing. Asking why Berlin should be an exemplary team player when others are not misses the point. It misunderstands Germany’s unique potential role and what even Berlin acknowledges is its “special responsibility” for European security.

Team-play would enhance Germany’s power

Unless it changes, Germany risks repeating past mistakes. During the eurozone debt crisis, Germany judged it was making huge leaps, at least when measured against its own domestic taboos. This assessment was not shared by partners. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government then became dismissive, pushing aside countries such as Poland that were in fact keen to contribute and trying to bear the burden alone to Europe’s detriment—and Germany’s.

Now, Germany is again pursuing its own version of the “Sinatra Doctrine.” And once again the United Kingdom, France, Central and Eastern European states, and the United States would welcome Berlin changing its tune from “My Way” to proposing ambitious ideas well-coordinated with allies. This would set the ground for Germany to get a fairer hearing and jointly shape constructive ways forward—and exercise greater power.

Crucially, this power would be welcomed as a force for the common good of Germany and its allies. Team-play provides a template to help Berlin better understand itself and the role it should play in Europe. Moreover, it would help Germany to more strategically pursue its real interests in combination with its values—as the new National Security Strategy asserts it should.

Roderick Parkes is deputy director of the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) where he heads the Alfred von Oppenheim Centre for the future of Europe.

Benjamin Tallis is senior research fellow at DGAP, where he heads the Action Group Zeitenwende.

A version of this article originally appeared in Der Spiegel in German. It is reprinted here with the authors’ and publisher’s permission.

Further reading

Wed, Jun 14, 2023

The hits and misses in Germany’s new national security strategy

New Atlanticist By

Chancellor Olaf Scholz has just released Germany's national security strategy. Atlantic Council experts answer the most urgent questions about the document and the path forward for this major European power.

Mon, Jul 31, 2023

Germany’s ‘Zeitenwende’ was spinning. Boris Pistorius is trying to set it straight.

New Atlanticist By

The actions of Germany’s defense minister are now aligning more fully with the lofty ambitions laid out in Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s February 2022 speech.

Fri, Jul 14, 2023

Is Germany shifting its approach on China?

New Atlanticist By

Germany released its first-ever China strategy. Experts weigh in on what this means for the future of relations between Berlin and Beijing.

Image: German Chancellor Olaf Scholz (SPD) speaks in front of a DFB logo during a visit to the DFB campus.