Get an inside look at the IMF-World Bank meetings as finance leaders navigate a geopolitically fragmented world

According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, countries need to relearn how to work together to achieve mutual prosperity.

But with finance ministers and central bank governors gathering in Washington for the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings, there may only be time for a crash course in cooperation, as they look to tackle challenges ranging from inflation to slow gross domestic product (GDP) growth to debt crises and beyond.

To gauge whether delegates can revive the spirit of cooperation in this geopolitically fragmented moment, we sent our experts to the center of the action in Foggy Bottom. Below are their insights, in addition to takeaways from our conversations with financial leaders outlining the global economy’s outlook for the coming years.

The latest from Washington

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank week: A look at the seeds that were planted

The “loop-the-loop circuits” of global remittances need straightening out—and fast

See all our programming

OCTOBER 26, 2024 | 11:57 AM ET

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank week: A look at the seeds that were planted

Over at the IMF, leaders and delegates can finally wind down, with the final day of the week having fewer meetings, bilats, and events. There are reasons to commend the progress made just before or during the annual meetings, as the IMF reformed its subsidized lending policies and released a new “debt-at-risk” framework that quantifies risks associated with debt projections. In addition, Group of Twenty (G20) ministers officially endorsed a plan outlining next steps for the World Bank’s strategy for reform. However, the fate of the World Bank’s goal to replenish the International Development Association, while supported by some sizable commitments, remains uncertain.

In fact, much felt uncertain this week, with the US election whipping up doubt about Washington’s future commitment to the Bretton Woods institutions. A shock in the United States—the largest shareholder in both institutions—would reverberate across the global economy. The institutions and the ministers were reluctant to give direct public comments on the topic, deeming it to be a purely domestic issue. But, as became clear in private conversations we had on the ground, anxiety about the election behind closed doors was unmistakable.

The tension was also palpable when it came to China’s domestic economy. Europeans are concerned about retaliation after the recent vote on electric-vehicle tariffs, hoping to avoid tit-for-tat escalations. Food and energy exporters in the Middle East, Asia, and South America are worried about the future of their exports if the Chinese economy continues to slow, leading to a drop in demand.

Major announcements were missing this week, which contrasts with what we saw last year in Marrakesh, where leaders were able to achieve significant progress on quota reform and debt restructuring deals. But true change in international economics and finance takes years, and quiet diplomacy could help prevent problems from escalating. Mark your calendars to join us at the Spring Meetings, as we return to see if the seeds planted behind closed doors this week flourish—or wither.

OCTOBER 26, 2024 | 10:01 AM ET

The “loop-the-loop circuits” of global remittances need straightening out—and fast

There’s one phrase I’ll never forget from this year’s IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings: “Funny loop-the-loop circuits.”

That is how European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde, speaking at the Atlantic Council on Wednesday, characterized the process of sending remittances—money migrants send back home. She explained that sending remittances “takes forever” and “is very expensive,” and the money “does funny loop-the-loop circuits around the world” along the journey.

Lagarde wasn’t the only one to hone in on the issue, as this week in Washington, the topic of remittance payments—usually confined to technical discussions and policy footnotes—took center stage in several discussions. But Lagarde’s remarks highlight the complex journey remittances often take, in which funds pass through multiple correspondent banks, undergo regulatory compliance checks, and face currency exchange fees, leading to delays and higher costs as the money “loops” through various intermediaries before reaching the final destination. The numbers paint a compelling picture: Last year, global remittance flows (valued at $890 billion) surpassed both foreign direct investment and official development assistance, making them an increasingly vital source of income for emerging markets. Today, the average cost of sending remittances stands at 6.4 percent—more than double the World Bank’s target of 3 percent by 2030. In some corridors, such as Tanzania to South Africa, the cost can be even higher: For example, it can cost nearly one hundred dollars to send two hundred dollars.

Ahead of the meetings, my colleague Ananya Kumar and I outlined a twenty-first-century approach to remittances, advocating for the introduction of more digital solutions in financial systems and enhanced private-sector collaboration and experimentation in digital infrastructure to reduce costs and increase speed.

But technology alone isn’t the answer—the regulatory framework also needs to evolve. Remittances are inherently a global issue: They cross borders, link multiple payment systems, and involve migrants who navigate between different national economies, making it impractical to address their challenges through domestic policies alone. This situation calls for coordinated action from international bodies like the IMF and World Bank, and support from South Africa’s Group of Twenty presidency.

DAY FIVE

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank week: Slow and steady may no longer suffice

An evasive—and elusive—G20 communiqué

Don’t forget about regional development banks. They play a key role in a Bretton Woods 2.0.

There’s plenty of worry—but not much talk—about China’s economy

OCTOBER 25, 2024 | 5:42 PM ET

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank week: Slow and steady may no longer suffice

Well, the week has nearly come to an end, except for a few talks. The plenary speeches have been delivered, and the IMF’s and World Bank’s ministerial-level forums (the International Monetary and Finance Committee and Development Committee, respectively) have come and gone.

When the dust settles tomorrow after another round of consultations and seminars—despite some important, albeit incremental, policy changes—it’s unlikely that very much will be remembered to distinguish these annual meetings from their recent predecessors.

The most important IMF reform, which actually was agreed upon earlier this month, will provide additional assistance to low-income countries that come to the IMF hat in hand during a crisis. Wealthier countries agreed to contribute additional resources to a fund that finances concessional loans to the poorest countries to the tune of an additional $3.6 billion of lending a year. The IMF is also moving to cut the charges and surcharges imposed on borrowers, which will reduce the repayment burden that countries face.

But on the long-term issues facing the global economy, which is still trying to regain higher levels of growth in the post-COVID era, the messages from the meeting sound too familiar: raise productivity, implement labor market reforms, pursue the “green transition,” and improve people’s lives. Indeed, these goals have been outlined at several previous annual meetings, but progress is slow.

That is one of the basic truths of the multilateral process. Change comes slowly, when it comes at all. But in a world facing a rising tide of geopolitical fragmentation, wars, debt crises, and demographic change, incremental change may no longer suffice. Sometimes slow and steady just means sclerotic.

OCTOBER 25, 2024 | 3:16 PM ET

The intensification of war in Lebanon has “flipped” the country’s economic priorities “180 degrees,” says minister of economy and trade

At the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings, Lebanese Minister of Economy and Trade Amin Salam has sensed a shift in conversations, and priorities, with the Bretton Woods institutions regarding Lebanon.

“A few months ago, we were looking at reform and recovery. . . we were looking at a deal with the IMF,” he said in a conversation with senior economist Perrihan Al-Riffai. “Now, everything has changed.”

That deal, slated to include a three-billion-dollar loan to “kickstart the economy,” was the subject of a staff-level agreement in 2022. (According to the head of the IMF mission to Lebanon, the deal stalled amid Lebanon’s slow implementation of promised reforms). The three-billion-dollar loan, Salam said, was supposed to be a “stamp of approval” or a sign of trust in the Lebanese economy, encouraging investment. But the intensification of Israel’s war against Hezbollah in recent weeks, including airstrikes in Beirut and a ground campaign in southern Lebanon, “really flipped the equation 180 degrees,” with economic conversations focusing on sending aid to Lebanon to help the economy recover—and with investors looking elsewhere.

Speaking at the Atlantic Council interview studio at IMF headquarters, Salam looked back on the challenges his country has faced before today’s war: a financial crisis in 2018, the COVID-19 pandemic, impacts from the war in Ukraine, and the Beirut port explosion in 2020—which destroyed “half the city,” Salam explained.

“Lebanon has witnessed a sequence of different challenges . . . that hit the socioeconomic scene,” he said. “There is no economy in the world that can really tolerate or that can handle so many different challenges . . . within such a small amount of time.”

Salam said that the tourism and agriculture sectors, which were the “oxygen of the economy,” have been particularly impacted. That raises fears, he said, that if the war continues and if Lebanon keeps “spending without income,” it will have to tap into its reserves. “That is unhealthy for the economy,” he explained.

The country needs $250 million monthly “just to handle the emergency situation,” Salam explained, pointing to the rising costs required to support displaced people, provide food, and maintain health services. That would amount to $3 billion a year. Yesterday, international partners at a conference for Lebanon in Paris pledged $1 billion in aid, including $200 million for Lebanon’s security forces.

Salam praised the Paris conference for filling the needs gap, as once the war became more intense this year, countries that began helping Lebanon were only able to meet a small fraction of the needs. He said that the funds geared toward security forces will help the country comply with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1701, which is intended to prevent conflict along the country’s border with Israel. That, he said, requires sending the army to “create a safe and peaceful zone.”

While his country is pushing for humanitarian aid, it “is not the solution,” Salam said. “The solution is the ceasefire.”

“The more we extend this war, the wider the scope gets . . . the more the needs are, the more the billions will accumulate that we will need in emergency help,” he said.

Watch the full event

OCTOBER 25, 2024 | 2:05 PM ET

European Commissioner Jutta Urpilainen: Investing in Europe’s security requires investing in international cooperation and partnerships

European Commissioner Jutta Urpilainen argued Friday that while the European Union (EU) focuses on boosting its security and competitiveness, it must not fail to invest in its international cooperation and partnerships.

“We are living in a very interconnected and intertwined world,” she told Atlantic Council Europe Center Senior Director Jörn Fleck. While the European Union bolsters its “hard security,” she said, it must also address other security threats, such as terrorism and even climate change. “And that means,” she added, “that we have to also invest in our international cooperation and international partnerships.”

Urpilainen explained that over her five-year term, the COVID-19 pandemic and the increasing size of the youth population across the Global South has changed Europe’s “playbook” when it comes to development. The pandemic, she said, showed Europe how it needs to “coordinate our efforts with set common objectives” and collaborate in more ways, such as pooling resources; meanwhile, the rising number of young people in partner countries has taught Europe it needs to “invest in youth” and work to empower them.

The commissioner also said that she saw a new dynamic form, in which partner countries in the Global South no longer wanted to be the “subject of aid,” but rather wanted to work with the EU on reforms and improving their resilience. That, she added, is the model behind the European Union’s Global Gateway strategy to invest in infrastructure projects worldwide.

There are several reasons behind the 300-billion-euro plan, Urpilainen explained. One is the “huge gap of investments” across the EU’s partner countries. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, she noted, would take trillions of dollars in additional investment each year. But another reason is that, amid intensifying geopolitical competition, competitors such as the EU are engaged in a “battle of offers,” she explained. “We need to have our own European offer to our partner countries.”

She noted that, for the EU, “it’s very important to respect very [high] standards in terms of environment and social standards,” she said. “We don’t want to create new dependencies. Instead, we really want to strengthen the resilience of our partner countries.”

Urpilainen also said that development actors and leaders aren’t working closely enough to exchange ideas and information—and thus to achieve better results. “We work too much in silos as an international community. I think we very much share common objectives when it comes to sustainable development goals,” she said. “We should get out of these silos.”

Watch the full event

OCTOBER 25, 2024 | 1:20 PM ET

An evasive—and elusive—G20 communiqué

The gathering of Group of Twenty (G20) finance ministers at the IMF-World Bank meetings used to make news. Reporters would devote megabytes of copy to the communiqués, which often overshadowed the Fund’s own pronouncements. But this year, the document has been harder to track down than tickets to a Taylor Swift concert. The website of the G20’s 2024 “rotating presidency” (Brazil), has been silent on the topic so far, and most news organizations have given it a miss.

I finally found the communiqué thanks to Japan’s Ministry of Finance, and it’s understandable that it isn’t grabbing headlines. The thirty-five dense paragraphs do contain discussion of a multitude of important issues—from the ten downside risks facing the global economy to inequality and climate change to a “Roadmap towards Bigger, Better, and More Effective” multilateral development banks. But concrete proposals are a bit lacking. Instead, the ministers cite a vast range of reports, working groups, and reviews, all of which work toward building elusive consensus among a group increasingly riven by geopolitical differences.

A few years ago, the pressing problem of developing-country debt was at the forefront of the ministers’ deliberations. But that issue has been relegated to one paragraph that “welcomes” meager progress in restructuring a few countries’ obligations. Meanwhile, the ministers gloss over the social cost of the debt and its centrality to their headline issues of climate-change mitigation and sustainable development.

It is notable that the communiqué is silent on the biggest global issues: Ukraine and the Middle East. However, Reuters reported that the Brazilian chair issued a statement saying “members had differing views on whether the conflicts should be discussed within the group.” That statement has not been officially posted either.

All of this suggests that the brief era in which it was believed that twenty governments from advanced and emerging market economies could work together productively in a single multilateral forum may be fading into posterity.

OCTOBER 25, 2024 | 12:27 PM ET

Don’t forget about regional development banks. They play a key role in a Bretton Woods 2.0.

As the World Bank and International Monetary Fund turn eighty, multilateral development bank reform is atop everyone’s agenda this week.

The agenda extends beyond the Bretton Woods twins, however, to include the regional development banks (known as RDBs)—the EBRD (Europe), AfDB (Africa), ADB (Asia), and IDB (Latin America), among others. As Undersecretary of the US Treasury Jay Shambaugh noted in his annual-meetings preview speech at the Atlantic Council, RDBs “have become critical sister institutions to the World Bank and IMF, complementing and deepening the impacts of the Bretton Woods system”

In the context of COVID-19, I wrote that RDBs have a critical role to play in recovery given their agility, complementarity, and continuity.

This is arguably even truer—and these traits more crucial—today in the face of ongoing shocks and a tenuous economic landscape marked by debt, conflict and fragility, fragmentation, demographic pressures, and extreme climate challenges alongside opportunity in the green and digital transitions. The ability of RDBs to specialize, be context vigilant, pivot more quickly to respond to changing needs, and seize investable opportunities differentiates them in the international financial system. These sentiments were echoed in my conversation on Thursday with EBRD President Odile Renaud-Basso: “We can react quickly to events and adjust to the needs of the country; the war in Ukraine for example tested our agility to come up with quick solutions.”

And as the Bank and Fund (and let’s not forget the World Trade Organization) evolve in governance and operational capabilities and efficiencies, new paths and platforms for collaboration and coordination with the RDBs are being created or expanded. For example, AfDB has partnered with the World Bank on Mission 300, a joint initiative to connect 300 million people in Africa to electricity by 2030; and Ajay Banga updated this week that in the just the first six months of the Global Collaborative Co-Financing Platform (announced in April by ten multilateral development banks), more than one hundred projects are in the pipeline.

Given their size and global reach, it is easy for the Bretton Woods institutions to garner all the attention. But ensuring RDBs and all actors in the international financial system are fit for purpose and aligned can bring meaningful scale, efficiency, innovation and impact.

OCTOBER 25, 2024 | 9:49 AM ET

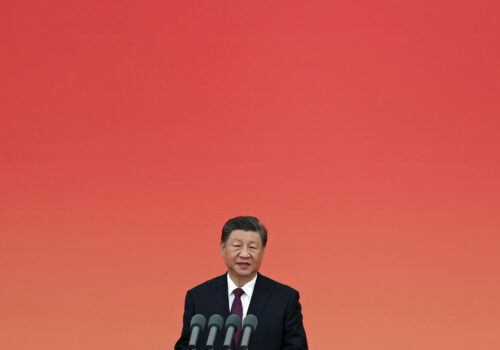

There’s plenty of worry—but not much talk—about China’s economy

Seats in the IMF’s atrium started filling up a full forty-five minutes before the Fund’s biannual Debate on the Global Economy, with guests lining up in the back and sides for this standing-room-only event.

The panel, which included IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, discussed the global economic outlook, lingering stress on consumers from elevated prices, liquidity challenges, and limited room for fiscal maneuvering. Without getting into politics, the speakers referenced the US election and the importance of the United States as the “anchor of the multilateral system.” In the same breath, they debated why the United States had such a proclivity for trade barriers compared to the EU’s relative openness. Why would the US be more fearful about China’s threat to its jobs and manufacturing, while European peers’ economies were actually slowing?

Part of the answer they provided was that the United States could afford to be more protectionist and isolated. I delved deep into possible US approaches to tariffs with China in conversation with former National Economic Council Deputy Director Clete Willems on Tuesday. Our conversation leaned more towards the argument that the United States, with its outsized economic weight, could use tariffs as leverage for more suitable terms of trade globally. At the same time, however, the United States needs to provide better incentives to trading partners and put market access back on the table.

Surprisingly, in the IMF’s conversation about the outlook for global growth and major economies’ fiscal positions, one country’s domestic situation wasn’t discussed: China. According to Bloomberg calculations, based on the IMF’s own World Economic Outlook forecasts, China will be the largest contributor to global growth for the next five years. The panel’s time was limited to just an hour, of course, but it’s still puzzling why more time wasn’t spent on the world’s second-largest economy.

DAY FOUR

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank week: Gray clouds are rolling in…

Europe must have “its own view” on trade and tariffs, says Spanish Minister of Economy Carlos Cuerpo

Irish Finance Minister Jack Chambers: The US and EU must “guard against” rising protectionism

How low-income countries fare in the flagship publications

A look at what’s behind all the talk on payments in Washington and Kazan this week

OCTOBER 24, 2024 | 5:32 PM ET

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank week: Gray clouds are rolling in…

“Let’s achieve inclusive growth” here, “boost green finance” there. Along 19th Street in downtown Washington DC, the familiar pageantry of the IMF-World Bank meetings is in full bloom, carrying slogans that call upon delegates and visitors to end poverty and collaborate on a bright future for the citizens of the world.

As a former IMF official, I remember the energy and optimism conveyed by this colorful redesign of the Annual Meetings a little more than a decade ago. There was a genuine belief around the world that the global powers could work together peacefully in the Bretton Woods institutions and the, at the time, relatively young Group of Twenty.

Today’s reality looks starkly different, unfortunately. Large countries seem less and less willing to put aside domestic interests in favor of the multilateral process. Autocratic countries would like to end the dollar’s dominance, and a new trade war looms on the horizon as the World Trade Organization fades into oblivion. And Western democracies themselves face populist movements for whom the values espoused by the posters in Foggy Bottom remain an ideological (and budgetary) anathema.

There is still value in holding face-to-face meetings for finance officials in Washington, of course. Quiet diplomacy may be able to avoid an escalation of problems, and an increasing focus on helping low-income countries seems to be the common denominator that still leads to meaningful policy decisions. There is intense geopolitical competition for the “Global South,” which helps facilitate agreement on issues such as the IMF’s reform of its subsidized lending policies and the World Bank’s impending replenishment of its International Development Association, for example. But these accomplishments pale in comparison with the challenges at hand.

The colorful posters that flank 19th Street are becoming a relic of times past. They stack up against a reality of record debt levels, widening inequality, and a hotter planet. There is still time to turn things around, but inside the buildings, blue-sky optimism has long given way to the gray clouds of realism.

Watch more

OCTOBER 24, 2024 | 4:15 PM ET

Ukrainian Finance Minister Serhiy Marchenko on how his government hopes to use its new $50-billion loan

During a week when the United States and its G7 partners will approve some $50 billion in loans to Ukraine backed by immobilized Russian assets, Ukrainian Finance Minister Serhiy Marchenko sat down with GeoEconomics Center Deputy Director Charles Lichfield to discuss how Kyiv hopes to use the money.

The loan—part of the Group of Seven (G7) Extraordinary Revenue Acceleration of Ukraine announced in June this year—“helps us at least to think about some possible relief,” Marchenko said, explaining that he hopes the funds will help cover Ukraine’s current financing gap and also help with medium-term goals over the next few years.

“There are some discussions about additional military needs,” he said, referring to the United States’ suggestion that it will devote half of its $20-billion contribution to military assistance provided it can get a new appropriation through Congress. He added that the government intends to use “at least part of this money” for reconstruction.

On international support, Marchenko spoke about the Ukraine Recovery Conference. He said that instead of looking forward to next year’s convening in Rome, he would prefer to look back on “what we already achieved,” such as cooperation agreements and various memorandums. “We shouldn’t try to create some new vehicle in Rome,” he said. “We should track our decisions, which were made during London and Berlin, and then think about how to implement [them].”

Watch the full event

OCTOBER 24, 2024 | 2:51 PM ET

Europe must have “its own view” on trade and tariffs, says Spanish Minister of Economy Carlos Cuerpo

“Europe has to have its own view and its own position” distinct from both the United States and China when it comes to trade and tariffs, said Carlos Cuerpo, the Spanish minister of economy, trade, and business. Cuerpo appeared at an Atlantic Council event on Thursday in conversation with GeoEconomics Center Senior Director Josh Lipsky.

Spain abstained from voting on the European Union’s decision this month to adopt tariffs on Chinese-made electric vehicles. Explaining this position, Cuerpo said Spain is “a very open economy that actually thrives thanks to multilateralism” and trade under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. But, he added, “It’s 2024. It’s not 2004. We have to be open, but we should not be naive.”

This approach, he said, requires protecting Europe’s strategic industries, including electric vehicles (EVs) and ensuring that Chinese EV companies “compete on a level playing field” with European ones. Stating that Beijing employs “unfair” and “asymmetric” EV subsidies, Cuerpo called for an “efficient use of the WTO as a way out of these controversies.” The need for an efficient WTO framework to resolve such disputes, he said, “has been forgotten” in the last few years.

Cuerpo also discussed the state of the Spanish economy amid lagging growth rates across the European Union. While acknowledging that structural unemployment was one of the “main challenges” for the Spanish economy, Cuerpo touted Spain’s low levels of inflation and its expected growth rate of 2.9 percent for 2024—the strongest among all advanced economies. “We expect that as our main partners do recover, we would have a tailwind going forward,” he said.

On Spain’s role in international financial institutions, Cuerpo noted that Spain’s banks are “ready to engage and to help” in the construction of a digital euro, as well as to take part in discussions with the European Central Bank on its development. He also spoke of Spain’s initiative to expand its aid to low-income and middle-income countries in South America, which includes an increase in its contribution to the World Bank’s International Development Association fund.

Looking ahead to the future of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, Cuerpo said that “we need to be bold in the way that we face what Bretton Woods institutions need for the twenty-first century.” But, citing the GeoEconomics Center’s work on a “Bretton Woods 1.5,” he added that before undertaking massive reforms, “we need intermediate steps that will help us arrive in a realistic way” at those bold objectives.

Watch the full event

OCTOBER 24, 2024 | 11:37 AM ET

Irish Finance Minister Jack Chambers: The US and EU must “guard against” rising protectionism

In a world in which deglobalization and conflict are unfolding, the world needs to reignite cooperation on trade to improve economies globally, said Irish Finance Minister Jack Chambers.

Chambers appeared at an Atlantic Council event on Thursday in conversation with GeoEconomics Center Deputy Director Charles Lichfield.

Earlier this month—with the EU’s investigation into Chinese subsidies for electric vehicles still underway—the European Commission voted in favor of imposing tariffs on the import of Chinese electric vehicles. Meanwhile, China has launched an anti-subsidy investigation into EU dairy products. Chambers said that it is important to “resolve [the electric vehicle] issue and indeed other issues that exist between the EU and China as it relates to trade.”

Ireland “promotes and supports free trade between all countries, and that’s something that has underpinned our wider economic development,” Chambers said. “We need to avoid a situation where we have tit-for-tat disputes or protectionism taking hold,” he cautioned, as that would “damage” the economy.

Trade is something that the United States and EU will need to work more closely on, Chambers said, including after the upcoming US presidential elections. The finance minister said that he is “concerned” about the “protectionist outlook taking hold” in the EU and United States. “We have to guard against that because it’s a net negative for everybody.”

In September, the European Court of Justice ruled that Ireland had given Apple (which has its European headquarters in Cork) illegal tax breaks; Ireland is now responsible for recovering those funds from the company. The government plans to use the fourteen-billion-euro windfall to invest in infrastructure.

“Obviously, we sought to defend a matter of interpretation on tax policy,” Chambers said. “We respect the outcome, but it was important we defended the tax policy that we had at the time.”

In discussing whether the ruling would dissuade multinationals from investing in Ireland, Chambers touted the country’s ability to give companies stability and predictability. “We’re confident that the system that we have presently is one that gives them that stability for the future.”

Watch the full event

OCTOBER 24, 2024 | 10:33 AM ET

How low-income countries fare in the flagship publications

Attention to developing-country issues in the IMF flagship publications is noticeably sparse at this year’s annual meetings. The World Economic Outlook offers only a limited assessment of the outlook for the swath of low-income countries that have lost ground since the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, a topic I wrote about earlier this week.

The Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR), whose headline messages my colleague Hung Tran previously summarized for this blog, does detail recent trends affecting the so-called “frontier markets.” These make up the group of developing economies that before the pandemic had become the darlings of sovereign lenders like China and institutional investors because of their solid growth and seemingly bright prospects. However, many of them fell into debt distress after 2020, and their interactions with lenders and investors shifted toward difficult debt-restructuring negotiations.

The GFSR reports that there has been “significant progress” on restructuring, a conclusion that many observers might consider to be overstated given the uncertain prospects for either sustainable growth or debt sustainability in countries like Ghana, Sri Lanka, and Zambia. But at the same time, the report chronicles that frontier economies have enjoyed “strong investor risk appetite” for new international bond issues, “although yields remained high.” Indeed, some 20 percent of those countries have had to offer yields “close to 10 percent or higher” above the rates on US Treasury bonds carrying a similar maturity in order to attract those investors. The GFSR also reports that about four billion dollars of frontier economy debt will have to be repaid before the end of this year, and about thirteen billion dollars will come due in 2024 and fourteen billion dollars in 2025. Nearly 60 percent of those maturing bonds carry yields close to 10 percent or above. This hardly sounds like grounds for confidence if the global economy hits an unexpected speed bump again.

OCTOBER 24, 2024 | 10:06 AM ET

A look at what’s behind all the talk on payments in Washington and Kazan this week

Events at the annual meetings this year have a special emphasis on payments and digital public infrastructure, reflecting the burgeoning emerging market interest in developing and deploying new technologies. The public and private schedule at the IMF and the World Bank this week is chock-a-block with events on digital payments: the macroeconomic impacts of them, issues of inclusion and technological infrastructure, and the nuts and bolts of putting these technologies to use. The Group of Twenty is a welcome entrant to this payments party, as it released its progress report on the roadmap for enhancing cross-border payments on Monday. But even as Washington seems all business this week, the BRICS summit—which is simultaneously underway in Kazan, Russia—is all geopolitics when it comes to payments.

Russian President Vladimir Putin opened the summit with an emphasis on the role of the dollar in the global financial system, saying that “the dollar is being used as a weapon.” BRICS members have stated their goal to develop an alternative payments channel to the dollar, which would allow them to continue trade and other activities. This is not a surprising proposal, considering the challenges Russia is facing as a result of the economic measures taken by the Group of Seven in response to the invasion of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022. Other BRICS members are more cautious about this announcement, looking to create short-term strategies for mutually beneficial trade relationships—such as increased invoicing in local currencies—while mulling over the long-term strategy of alternative payments channels. The BRICS members’ geopolitical interest in payments systems stands out this week, as discussions of payments systems not only encompass domestic economic considerations but also seek to address the impact on the global financial system.

DAY THREE

Bangladesh’s finance adviser on the interim government’s reform priorities

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank Week: Solving the inclusive growth puzzle

A warning from the IMF: Risks to financial stability ahead threaten to expose fragilities

Christine Lagarde on European competitiveness, US tariffs, and creating a digital euro

Two new publications show emerging-market credit risk is better than previously believed

The dark end of the WEO street

OCTOBER 23, 2024 | 8:09 PM ET

Bangladesh’s finance adviser on the interim government’s reform priorities

Less than three months after a caretaker government assumed power in Bangladesh, the country’s finance adviser, Salehuddin Ahmed, sat down with Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center Assistant Director Mrugank Bhusari to talk about the reforms the interim leadership is pursuing.

Ahmed explained the interim government will be working to implement “structural” changes across the country’s institutions, banks, insurance companies, markets, and beyond. They “have to be made efficient with the proper people,” he said, “and previously there was a lack of transparency and accountability.”

Over the long term, Ahmed said he hopes the interim government will “leave some footprint” so that the next government takes up those reforms instead of entering office and proceeding to “sweep everything under the carpet.”

Even as the IMF is forecasting Bangladesh’s economy to grow at 5.4 percent, its forecast did get a small downgrade. Ahmed said that such a downgrade was a “logical” and “rational calculation,” considering the slowing in economic activity the country faced in the beginning of the year and as student protests swept the country in the summer.

While Bangladesh is just about to graduate out of the group of least-developed countries, as determined by United Nations standards, Ahmed believes there’s still work to do. “I think we have done reasonably well,” he explained, “but the fruits of development, they have not gone to the people . . . because the rich have become richer. . . so we are now giving this attention,” by focusing on social development, education, and equal growth across the country.

While the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings are underway, leaders representing the BRICS bloc of countries—named for the core group of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—are also meeting in Russia. Bangladesh has applied to join the bloc, and Ahmed said joining BRICS is “still valuable” because Bangladesh wants to create a wider market for its garments and other products.

While Bangladesh is developing frameworks to process payments with Indian rupees and Chinese yuan, Ahmed said that he thinks the dollar will “be able to remain dominant.” But the country, he said, is having “some problems” making payments in dollars for a nuclear power plant Russia built in Rooppur, given that Russia has been banned from the financial messaging system SWIFT. Bangladesh decided last year to pay Russia in Chinese yuan.

Watch the full event

OCTOBER 23, 2024 | 6:15 PM ET

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank Week: Solving the inclusive growth puzzle

It’s day three, and the annual meetings are clearly in full swing on both sides of 19th Street and across town.

The security and cafeteria lines are longer. There are fewer, if any, empty seats at the events—even as organizers put on multiple simultaneous events to absorb enthusiastic delegates and attendees.

To that end, it was a full house this morning over on 15th Street at the Atlantic Council to hear European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde’s insights on the European economy and the international financial landscape, from inflation to digital currencies to decoupling. On many things, she struck a generally sanguine, if not cautiously optimistic, tone.

That positivity ended, however, when she was presented with the number (a measly 12 percent!) of finance ministers and central bank governors who are women, which she called “abysmally small.”

As Lagarde pointed out, more diversity in leadership leads to better outcomes. But, taking a step back, improving women’s economic participation and financial inclusion across the board helps solve many of the challenges leaders are convening in Foggy Bottom to discuss. For example, more women in the labor force and in entrepreneurship increases productivity (improving growth) and boosts tax revenues (easing debt).

It’s a critical piece of the inclusive growth puzzle, along with creating opportunities for youth that can help usher in a demographic dividend. This requires better education and skilling on the supply side and generating more jobs on the demand side—and better aligning supply to demand. There’s no time to waste: 1.2 billion youth will enter the workforce in the next ten years, and only 420 million new jobs are projected (a data point repeated by World Bank President Ajay Banga again today, during a high-profile, packed-house event).

So if you’ve got a list going of issues and announcements to watch from the annual meetings, add “measures that address gender and generational inequality” right at the top.

OCTOBER 23, 2024 | 5:54 PM ET

Egyptian Finance Minister Ahmed Kouchouk on his government’s reform progress: “We’re not yet out” of economically difficult times

Seven months after the IMF agreed to increase its latest loan program with Egypt, Finance Minister Ahmed Kouchouk sat down with Racha Helwa, director of the empowerME initiative at the Atlantic Council, to talk about the deal and Egypt’s reform priorities.

On the latest extension of the program, Kouchouk said that “usually, every program has its own nature.” This one, he explained, is directed toward helping Egypt improve its current account imbalances that arose after the pandemic and also toward helping the country improve its oversight across public spending.

According to Reuters, the program had previously stalled amid delays to divesting public assets and increasing the role of the private sector. “I think private sector should be leading,” Kouchouk said, explaining that such an arrangement could be a solution for Egypt as it looks to increase production and growth while taking on less borrowing. “This is in the interests of everybody.”

In February this year, Egypt signed a foreign-direct-investment deal with the United Arab Emirates to develop the area of Ras El Hekma. “The structure” of the deal “is quite good,” Kouchouk argued, because it will swap eleven billion dollars in UAE deposits at Egypt’s central bank into foreign direct investment. “This investment will give them and give us a higher rate of return, so it’s a good deal.”

Kouchouk said that the reforms Egypt has thus far implemented, as part of its commitments, are helping support improvements in the economy. But “we’re not yet out” of economically difficult times, he said. “We still need to keep the course of reforms and to keep monitoring things.”

Kouchouk participated in the Atlantic Council discussion shortly after a Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action meeting. Before the group was formed in 2019, Kouchouk explained, he had seen many Sustainable Development Goals and other aspirations form without finance ministers in the loop—then finance ministers had to deliver the news that there was not adequate financing for those goals.

The coalition, he said, “lets us all benefit and learn. And it’s making us deal with financing of the climate challenges . . . in a much more proactive manner.”

Watch the full event

OCTOBER 23, 2024 | 3:45 PM ET

The number of finance ministers and central bank governors who are women is shockingly low. Here’s what that means for the economy.

This week, on the ground at the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings, the gender gap in global economic leadership is glaringly apparent. Only twenty-two of the 191 IMF countries have women as finance ministers, and twenty-four have women as central bank governors—significantly lower than the average proportion of women in cabinet minister positions globally.

During a conversation this morning between European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde and Atlantic Council CEO and President Frederick Kempe, our team shared research illustrating that only 12.3 percent of finance ministers and central bank governors are women. “I think it’s abysmally small and does not reflect the availability of talents and merits that many economists and macroeconomic experts and financial experts have around the world. There’s a whole pool of talent that is not tapped into . . . but it’s also a lack of diversity,” Lagarde commented.

Lagarde is the first female finance minister of a Group of Seven economy, the first woman to head the IMF, and the first female president of the ECB, so she is no stranger to the barriers women face in this field. She concluded, “We all know from having studied that and practiced it, that diversity is a source of better decision, of more stability, of better [outcomes] altogether—whether it’s in the financial sector or otherwise . . . we should learn that lesson and just do it.”

Explore the research

OCTOBER 23, 2024 | 3:21 PM ET

A warning from the IMF: Risks to financial stability ahead threaten to expose fragilities

As I wrote yesterday, the IMF’s World Economic Outlook presents a rather benign view (to quote, “stable yet underwhelming”). But its sister publication, the Global Financial Stability Report has called for policymakers to remain vigilant about medium-term risks to global financial stability. It identifies two main sources of that risk.

The first is the lofty asset valuation around the world, driven by accommodating monetary and financial conditions for too long. Indeed, the price-to-earnings ratio for the S&P 500 index—a standard measure of stock market valuation—has reached 29.6, or one standard deviation above the long-term mean of 19.26. Historically, stock markets have tended to correct when valuation gets much higher than that. Furthermore, public and private debt levels are high, as is the leveraging used by financial institutions in their portfolios. These frothy asset valuations can amplify future financial shocks.

The second is the disconnect between very heightened uncertainty generated by geopolitical rifts and low levels of measured market volatility. This disconnect could cause a surge in volatility when geopolitical conflicts materialize, catching market participants off guard and triggering disorderly market conditions.

This is a timely reminder to policymakers and financial regulators around the world to use the time immediately ahead—while many risks are still contained thanks to the economic soft landing—to strengthen the resilience of financial institutions, so as to be better prepared for future turmoil.

OCTOBER 23, 2024 | 3:11 PM ET

Christine Lagarde on European competitiveness, US tariffs, and creating a digital euro

The role of a global reserve currency should “never be taken for granted,” said European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde on Wednesday at an Atlantic Council Front Page event on the sidelines of the International Monetary Fund-World Bank Annual Meetings.

Lagarde addressed a host of issues facing the continent, including the European Union’s (EU’s) ambition to create a central bank digital currency (CBDC), the ECB’s efforts to keep prices stable, what Europe’s lagging economic competitiveness means for the ECB’s fight against inflation, and the outsize impacts that the next US president’s approach to trade will have on the global economy.

Below are more highlights from this conversation with Lagarde.

Read the highlights

OCTOBER 23, 2024 | 10:15 AM ET

Two new publications show emerging-market credit risk is better than previously believed

The International Finance Corporation (IFC)—a member organization of the World Bank Group—has released two important studies, which unfortunately have been buried by the busy talks about other issues at the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings this week.

The studies are from the Global Emerging Market Risk Database Consortium of twenty-six multilateral development banks and development financial institutions. The publications provide detailed information on credit risk in emerging markets and developing economies based on the investment experience of consortium members.

On their lending to private entities in emerging markets and developing economies, the average annual default rate is 3.56 percent—broadly aligned with many non-investment-grade companies in advanced economies; the average recovery rate is 72.2 percent—higher than many global benchmarks.

On their lending to sovereign and sovereign-guaranteed borrowers, based on forty years of experience, the average annual default rate is 1.06 percent and the average recovery rate is 94.9 percent—much better than previously assumed by many in the financial markets.

While this data reflects the unique experience of multilateral development banks and development finance institutions, it can provide useful input for the private sector’s lending and investment decisions. This is important as the world’s governments and multilateral development banks have tried hard to catalyze private capital to invest in emerging markets, developing economies, and low-income countries, especially in climate-mitigation and energy-transition efforts—to complement meager public investment efforts.

OCTOBER 23, 2024 | 9:26 AM ET

The dark end of the WEO street

Sometimes it makes sense to look at the downside. That’s certainly the case with the World Economic Outlook (WEO), whose authors always devote considerable thought to what could go wrong—and right, although the sunnier outlook always gets less attention. In the latest report, there is a lengthy box in the first chapter with the catchy title “Risk Assessment Surrounding the World Economic Outlook’s Baseline Projections,” which delves into the scenarios and “confidence bands” that give greater texture to the IMF modeling.

But for many readers, the real meat of the report from issue to issue is the section that details “risks to the outlook,” which this time around are “tilted to the downside.” Assembling the WEO is always a process of negotiation. While the IMF Research Department holds the pen, it inevitably must reflect the input and pressures from other departments, IMF management, and the always prickly membership—especially the most important governments that have their own view of how their economies should be presented. Small wonder, then, that some Fund insiders say that the most accurate view of the outlook sometimes can be found in the downside risk section.

In this WEO, most of those risks focus on systemic issues: how the recent cycle of monetary tightening might bite “more than intended,” leading to financial market repricing; intensified “sovereign debt stress” in emerging markets and developing countries; renewed “spikes” in commodity prices; increased protectionism; and a “resumption” of social unrest around the world (which, according to an accompanying chart, supposedly has subsided of late—not that most of us would notice). But one country is singled out: China. That’s because of a scenario in which the country’s already struggling property market experiences a deeper-than-expected contraction. China, of course, did the WEO authors no favor by announcing wide-ranging measures to put a floor under its housing market in the weeks leading up to the annual meetings, when the report was largely done and dusted. As much as anything else in the WEO, this risk bears close scrutiny in the coming months.

DAY TWO

Reading between the lines of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank Week: “Stable yet underwhelming”

A crack in the BRICS: Iran’s economic challenges take center stage at Russia’s summit

A bleak paper on the plight of low-income countries

OCTOBER 22, 2024 | 7:02 PM ET

A tale of two town halls

As an expert at a think tank, I registered as a representative of a civil society organization (or, as the IMF and World Bank say, “CSO”) and thus joined both IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva’s town hall yesterday and World Bank President Ajay Banga’s event today. They followed the same format: opening statements from the principal followed by moderated Q&A with the in-person and online audience. Both were well attended. Both were substantive and informative. And both covered a fairly wide range of topics.

But, like the institutions themselves, they differed in style and vibe, as well as in the substance.

On style, Georgieva and the moderator were both seated the whole time, while Banga (or Ajay, as he prefers) and his moderator were standing—he delivered his opening speech from a podium, then onstage with a handheld mic. Also notably, he introduced and engaged other executives in responding to questions, including World Bank Managing Director of Operations Anna Bjerde. Taken together, I found the Bank event more informal, candid, and inviting.

On substance, Georgieva touted progress both in the global fiscal situation and the IMF’s operations but reiterated her curtain-raiser message: “We can do better.” She said this message also applies to the extent and nature of the IMF’s engagement with civil society. Perhaps surprisingly, audience questions were limited on debt and fiscal matters, instead skewing toward “macro-critical” issues ranging from dealing with conflict and fragility to addressing climate change, and from gender to governance, even though the Fund is arguably still debating about the extent to which it should be addressing such issues. Banga focused on how he and his team are delivering towards “building a better Bank,” the charge he was given when he took the helm eighteen months ago—bringing speed and simplification to both the money and the knowledge sides of the Bank. He prioritized jobs and enabling environments and made a pitch for International Development Association (IDA) replenishment, telling governments “I need your help” in making the case for them to ante up and even increase their contributions. Questions ranged from addressing informality to operationalizing callable capital to supporting conflict-affected people and beyond.

In the end, we CSO representatives may not have heard anything new, but the commitment and level of engagement and transparency is arguably new and worth acknowledging in and of itself. And for participants like me who like to understand, compare, contrast, and ultimately influence what’s happening on both sides of 19th Street and the Bretton Woods institutions’ varying perspectives, reforms, and impacts, it was two hours very well spent.

OCTOBER 22, 2024 | 6:51 PM ET

Reading between the lines of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook

Just hours after the IMF released its World Economic Outlook (WEO), three Atlantic Council experts sat down at IMF HQ1 to talk about the updated growth forecasts for countries worldwide and about the reforms needed to boost growth.

Martin Mühleisen, a former IMF official, pointed out that this WEO was likely easier to write than the last couple of editions, because just before the October 2023 and April 2024 WEOs released, “big shocks”—in the form of war in the Middle East—occurred, and the IMF team had to “scramble” to incorporate how those events would impact the economy. But while this WEO may have been easier to write, it also “presents a different kind of challenge” because of the upcoming US elections, Mühleisen argued. He added that growth numbers are in a way “tentative” because the outcome of the US elections will trigger “volatility that we can’t really assess at the moment,” which could be good or bad for the global economy.

But in the medium term, Mühleisen said, growth looks “lower than anything we had in the past,” and “trade, geopolitics, [and] inflation surprises just add to the fact that we’re probably going to see a somewhat lower trajectory on average over the next couple of years.”

Nicole Goldin, a former consulting economist with the World Bank, pointed out that the WEO reflects “relatively stable” global growth overall, but emerging markets and developing economies are seeing low projections. Conflict is playing a role in that, as wars have a “somewhat disproportionate impact” on emerging markets and developing economies. Debt also plays a role in these low projections, she added. Hung Tran, a former IMF official, added that low-income countries falling further behind “will be a big problem socially [and] politically” for the world economy.

While the IMF has struck a positive tone in seeing countries achieve a soft landing in the battle against inflation, Tran clarified that inflation might just be slowing because of “lower activity,” meaning that while inflation for goods has shrunk dramatically, inflation for services is sticky. That, he said, is “something that we need to keep an eye on.”

The IMF has called for a “policy triple pivot” to protect from risks to global growth. But, Tran noted, significant reforms will be required. “The political will and the political appetite to do that simply [are] not there,” he said.

Goldin pointed out a few policy changes that could help secure and boost global growth. One such measure is harnessing artificial intelligence (AI) to boost productivity. AI is “coming in as both the threat and the opportunity,” she said. Another change is for countries to balance punitive policies (such as tariffs and protectionist trade policies) with inducements (such as development financing) when working with other nations. Those “positive economic statecraft” tools can help “bring about the policy reforms that are needed,” she explained.

Watch the full conversation

OCTOBER 22, 2024 | 4:58 PM ET

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank Week: “Stable yet underwhelming”

One section heading in the World Economic Outlook released by the International Monetary Fund this morning aptly sums up the mood at this year’s annual meetings: “Stable yet underwhelming . . .”

The outlook is stable as major economies have managed to engineer a soft landing with inflation slowing, labor markets proving resilient, and GDP growth at 3.2 percent this year, unchanged from the IMF’s previous estimates (although the estimate for next year was revised down a touch, to 3.2 percent). However, behind that stability is a series of revisions worth taking note of. The US growth rate has been revised upward by 0.2 percentage points (to 2.8 percent) this year, and by 0.3 percentage points (to 2.2 percent) for 2025. The WEO shows that Asia continues to be the growth engine for the global economy, with India expected to grow by 6.7 percent this year and 6.5 percent next year, followed by Vietnam at 6.1 percent in each of the next two years. China is expected to undershoot its “around 5 percent” growth target, coming in at 4.8 percent this year and slowing further to 4.5 percent in 2025.

By contrast, euro area growth has been revised downward by 0.1 percentage points (to 0.8 percent this year) and by 0.3 percentage points (to 1.2 percent) next year. Also concerning is the downward revision of low-income countries’ growth by 0.2 percentage points (to 4.0 percent) this year and by 0.4 percentage points (to 4.7 percent) next year.

The growth estimates and revisions in the WEO are indeed underwhelming, a product of uneven global recovery from the many shocks of the past few years. More importantly, the world seems set for a period of low growth, triggered by challenges such as aging populations, weak investment, and historically low production efficiency—especially if countries fail to implement significant structural reforms to improve economic performance (but even the WEO admits such reforms face strong social resistance).

But there’s a second beat to the subhead in the WEO: “Stable but underwhelming—brace for uncertain times.” That points to factors that could tilt the balance of risks to the downside, but the WEO says nothing about the elephant in the room: the outcome of the US presidential election, which could heighten turmoil in geopolitical conflicts, trade wars, and social instability in the United States—the largest shareholder of both institutions. Such developments would trigger the need for a fresh set of revisions of economic forecasts.

Putting the WEO aside, two issues that IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva raised in kicking off the meetings did pique my interest, but they are drawing less attention. The first is that in facing climate change, countries should try to free up funds for the green transition by eliminating their fossil fuel subsidies—such subsidies amounted to seven trillion dollars in 2022. The second point is that countries should work together to set up AI regulations, not just to avoid the risks the technology poses but also to harness its ability to raise productivity, potentially boosting growth by 0.8 percentage points. If the IMF can get governments focused on that, it would be a great service to the Fund’s membership.

This week, our team will continue to tease out developments big and small from the annual meetings.

OCTOBER 22, 2024 | 2:48 PM ET

A crack in the BRICS: Iran’s economic challenges take center stage at Russia’s summit

This week, finance ministers and central bank governors from over 190 countries will gather in Washington, DC, for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank Annual Meetings. But there is another major economic event happening on the opposite side of the world. Leaders of the BRICS group are meeting in the Russian city of Kazan for their annual summit, with Iran’s new president, Masoud Pezeshkian, in attendance for the first time after his country officially joined the BRICS earlier this year.

Uncertainty continues to loom over Iran as Israeli officials pledge to retaliate against Tehran’s ballistic missile attack on Israel earlier this month. However, while most analysis focuses on Iran’s geopolitical objectives in the region, there has been less discussion about the severe economic constraints facing the regime. These challenges will be at the center of Iran’s priorities during its first BRICS summit.

Read the full analysis

OCTOBER 22, 2024 | 12:33 PM ET

The Bank of England’s Megan Greene on why interest rates “will probably have to end up a bit higher” than before the pandemic

According to Megan Greene, an external member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, the United Kingdom’s neutral rate of interest—the rate when there is full employment and stable inflation—has “probably risen a bit.”

“We’re not going back to the [interest] rates that we had pre-pandemic,” she said in an interview at the Atlantic Council’s IMF HQ1 studio.

Greene, in conversation with Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center Senior Director Josh Lipsky, said that she favors “more of a gradualist approach” to cutting interest rates in pursuit of the neutral rate of interest, commonly called “r star.” Back in August, she explained, she voted against an interest rate cut at the Bank of England based on various indications that inflation has been sticky. But the Bank voted 5-4 in favor of a cut.

“Now that we’re in a rate-cutting cycle. . . we should remain on a cautious and gradual path,” she said.

In September, the Monetary Policy Committee voted to hold rates steady, in part based on “uncertainty [about] what state of the world we’re in, off the back of a pandemic and a war in Europe,” she explained.

The committee, she added, has come up with three “states of the world” to map the future of the rate-cutting cycle: 1. Inflation is coming down as inflationary shocks ease, meaning the Bank won’t need to be restrictive. 2. Inflation persists somewhat, requiring the Bank to “bear down” on inflation. 3. There have been more structural changes in the economy that require the Bank to be “more restrictive for much longer.”

“I think it’s most likely that we’re in the second state of the world, where actually it requires monetary policy to bear down on inflation,” she said.

On whether there is a risk that the Bank is too restrictive heading into the next vote on interest rates in November, Greene said that relative to other developed economies, the United Kingdom’s “speed limit” for how much it can grow without it being inflationary “is pretty low,” due to low investment overall that has slowed productivity growth.

Speaking at the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings, Greene said that the institutions are “a microcosm for a better state of the world than the one we’re living in,” with conflicts happening in Europe and the Middle East. “People from different countries do come together over really good analysis to try to support those who are most vulnerable.”

Watch the full interview

OCTOBER 22, 2024 | 9:35 AM ET

A bleak paper on the plight of low-income countries

On a day when attention focuses on flagship publications like the World Economic Outlook and Global Financial Stability Report, it is always useful to dig into papers that will attract less attention. It’s well worth the time to read through a World Bank report on the deepening financial plight of low-income countries (LICs). Fiscal Vulnerabilities in Low-Income Countries: Evolution, Drivers, and Policies by the World Bank’s Joseph Mawejje offers a bleak view of where the world’s twenty-six poorest countries—home to 40 percent of all people living in extreme poverty—stand four years after the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The bottom line: Unlike most of the world, these nations have not rebounded from the brutal impact of the crisis on the global economy.

The study calculates that the average government debt-to-GDP ratio in these countries “increased by 9 percentage points in 2023 alone—the largest annual rise in more than two decades—to 72 percent,” driven largely by expanding fiscal deficits. Those deficits have “expanded markedly, from 1.2 percent of GDP in 2019 to 2.4 percent in 2023.” While that is relatively low compared to many advanced and middle-income economies, the LICs have much less ability to finance their deficits, especially as they have little recourse to raise money from scarce domestic sources. Instead, they try to obtain financing from abroad.

However, the study says that “net financial flows—including foreign direct investment and official aid—fell to a 14-year low in 2022,” the most recent year for which comprehensive data was available. That means these countries have to borrow, and most now are in, or at high risk of, debt distress. This underlines the importance of finding new approaches to debt relief, an issue that has vexed the IMF and World Bank for years—and is unlikely to be resolved this week.

KICKING OFF

Our experts outline what to expect from the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings

What’s behind the IMF and World Bank’s data dance-off

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank Week: What you won’t see on the agenda, and why it matters

All eyes on China as IMF-World Bank Week gets underway

The IMF needs to find its geopolitical bearing

The IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings in 2024: Five important issues to be addressed

OCTOBER 21, 2024 | 7:41 PM ET

Our experts outline what to expect from the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings

On the first day of the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings, three Atlantic Council nonresident senior fellows gathered in IMF headquarters to talk about what they’re hoping to see as the week rolls on—and to reflect on the changes that have been achieved since last year’s meetings in Marrakesh. Here are some highlights from the conversation.

- Central banks have done a “good job . . . so far” in slowing inflation, said Martin Mühleisen, a former IMF official. Hung Tran, also a former IMF official, added that while central banks have had some success, the structural reasons behind high inflation—including geopolitical competition, economic fragmentation, and trade friction—still exist, and will “feed and keep structural inflation higher.”

- Nicole Goldin, a former consulting economist with the World Bank, noted that prices are still high, and financial leaders will need to focus more on dealing with the fallout. “Inflation tends to impact those most vulnerable the most,” she said.

- Tran said China’s struggle to restore its growth and recover sustainably has been a surprise, and that China’s youth unemployment problem would play a part in burdening the growth potential “for many countries, including China, for years to come.” “That needs to be a high-priority item for the IMF,” he said.

- Mühleisen noted that over the past year, he has been struck by “the reality of much closer collaboration between different autocratic countries,” pointing to China’s support for Russia as it continues its war in Ukraine. He sees an “open competition between different camps,” adding that the United States, as a major shareholder in the IMF, will need to think about whether to freeze out countries in the autocratic bloc. In such a scenario, those countries, he explained, “will still be members,” but Western allies could “take decisions that the majority of the Western democracies take in their own interests.”

- Goldin said that she will be watching to see whether the Bretton Woods institutions can “walk and chew gum” to concurrently address both short-term issues such as debt distress and long-term issues such as liquidity pressures in countries. Mühleisen said that he would like to see IMF shareholders “insist on more accountability” for lending programs, which have not resulted in some countries implementing reforms they committed to earlier on in negotiations. “Shareholders need to think a bit more about what teeth they can give the IMF,” he said.

- Mühleisen expressed skepticism about whether there will be “any progress” on the matter of reforming IMF quotas in the short term. “That will drag on for some time, and as long as that is kind of on hold and not proceeding, I don’t think the IMF will be able to tackle much.”

- Tran is watching what the IMF does to mobilize the fiscal resources needed to adapt to and mitigate climate change. He pointed to the IMF managing director’s call to eliminate fossil-fuel subsidies, which Tran said is the “right approach,” in contrast to recent efforts to mobilize private-sector resources.

- Goldin said she’ll be watching whether the International Development Association, a mechanism of the World Bank, will be replenished and how the conversations around artificial intelligence evolve.

Watch the full event

OCTOBER 21, 2024 | 4:24 PM ET

What’s behind the IMF and World Bank’s data dance-off

It’s opening day of the annual meetings and there seems to be a new field of (friendly) competition between the IMF and the World Bank: data.

The Bank has evicted its swag store from the prime real estate at the atrium’s front entrance to the lower level (C1, just by the cafeteria entrance), swapping it with an interactive data exhibition complete with a supersized display of real-time indicators and statistics across its priority work areas such as gender, food and agriculture, electricity, the International Development Association, and corporate outcomes, courtesy of the Bank’s Scorecard launched at the Spring Meetings this year. There are large interactive touch screen monitors, too.

For its part, the IMF has set up a slightly less conspicuous stand on the second floor of HQ1, where it’s touting its new—and improved—portal. The updated platform consolidates data and statistics from fragmented sites across the Fund, including data.imf.org, DataMapper, the Regional Economic Outlooks, and the World Economic Outlook (WEO)—but don’t go looking for the latest WEO yet, which will be released tomorrow. The goal is that the data will be easier to find and, arguably more importantly, that it will be easier to use the Fund’s data to inform decision making, policy, and investments.

Truth be told, the IMF and World Bank’s data and research are complementary. And of course, emphasizing the importance of data and evidence is not new to either Bretton Woods institution, as both of their mandates include providing evidence-based advice, and they regularly publish statistics and analyses, research, and visualizations of their data. Both participate in data generation and data sharing initiatives. The Bank, for example, is a member of the United Nations-led Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, and both the Bank and the Fund are part of the Development Data Partnership along with a variety of multilaterals, international organizations, and companies.

Perhaps as multilateral reform efforts hit stride, pushing new data platforms and putting them on such display is an effort to signal or amplify to the broader development, economic, and finance communities that these institutions are even more committed to data-driven impact, open for data business, and keen to engage. As a believer in “you can’t manage what you don’t measure,” this data nerd is here for it.

PS: Check out the Atlantic Council’s Econographics for our data-driven analyses and visualizations.

OCTOBER 21, 2024 | 3:20 PM ET

Dispatch from IMF-World Bank Week: What you won’t see on the agenda, and why it matters

The world’s financial leaders are descending on Washington this week for the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings, but one of the most important issues for the future of the global economy won’t be on the official agenda.

While China’s economy, debt relief, and slowing inflation will all be at the top of the agenda for ministers, what everyone wants to talk about is the US election. They have good reason. The outcome will determine the trajectory on trade policy and tariffs in the world’s largest economy and may impact who is selected as the next Federal Reserve chair (Jay Powell’s term is up in 2026). It will also tell the world how the United States plans to engage—or not—in international economic collaboration over the next four years.

There is a reason why the US Treasury’s Jay Shambaugh has been arguing (as he did at the Atlantic Council last week) that the world needs the Bretton Woods institutions—and that without them, there would be a giant “IMF-shaped vacuum” in the global economy. He’s concerned that as the institutions mark their eightieth birthday, many around the world have forgotten why they were created in the first place.

It wasn’t only the ravages of World War II that forced the delegates in New Hampshire to build a new international financial architecture: It was also the trade wars of the 1930s, including the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act and retaliatory tit-for-tat tariffs, which prolonged and deepened the Great Depression.

I was in the room last week when IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, in her curtain-raiser speech ahead of the meetings, said trade was “exhibit one” of where the global economy can do better. For an institution that has a reputation for being focused on fiscal policy (the old joke is that IMF stands for “it’s mostly fiscal”), it was a telling choice. She knows, as does everyone coming to Washington this week, that the decision made by the American people on November 5 will impact every economy in the world.

It may not be on the official agenda, but you can bet we’ll be diving into the election this week.

OCTOBER 21, 2024 | 11:57 AM ET

All eyes on China as IMF-World Bank Week gets underway

One of the many big questions looming over the IMF and World Bank this week is how they will assess China’s recent efforts to revive its sagging economy. Faced with the challenging combination of a property crisis, deflation, a mountain of local-government debt, rising youth unemployment, and plummeting business and consumer confidence, Beijing has announced a series of efforts aimed at boosting growth. But so far, those measures seem to be falling short of what is needed, as I write this week.

No doubt, many officials and analysts will be looking to Tuesday’s release of the World Economic Outlook to gauge how the IMF assesses China’s shifting policies. Last week’s curtain-raiser speech for the meetings from IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva was silent on the subject, but in an interview with Reuters, she did hint at some concern about the course that Beijing is charting. She said that China’s economy has become too big for Chinese policymakers to continue relying on exports to drive growth. Instead, she said, China needs to shift toward reliance on consumption. Without such a shift, she said, China’s annual growth could fall below 4 percent in the medium term (compared with the government’s current target of “around 5 percent”). Such an outcome, Georgieva told Reuters, “is going to be very difficult for China. It’s going to be very difficult from a social standpoint.”

The most recent IMF forecast, released in May, projected 5 percent growth for China this year and 4.5 percent in 2025. But the Fund’s call for more domestic consumption, which has been a constant theme for the past decade, seems increasingly out of step with the direction of Chinese economic policy, which has been prioritizing the development of high-tech industries while brushing off criticism of rising exports.

Read more on China’s economy

OCTOBER 4, 2024 | 8:59 AM ET

The IMF needs to find its geopolitical bearing

The following is an abridged version of a recent article in Econographics. Read the full version here.

At the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings, Western delegates should think hard about how the financial and intellectual capital invested in the Bretton Woods institutions can be put to better use in the interests of democracies around the world.

The World Bank’s case is relatively straightforward (it needs more financing and efficient project implementation), while the IMF’s case is more complicated. The fund saw a major shift of its activities into climate and development lending in recent years, requiring several rounds of fundraising to increase its basic capital (or quotas) and build up trust funds to provide subsidized loans to lower-income members.

These efforts have recently borne fruit, allowing the fund to lower its lending rate for the poorest member countries. However, the IMF is increasingly running into budget constraints among its larger members, and it will need to push for better lending results. It should insist on more thorough debt restructurings before concluding programs with countries, many of which are mired in (Chinese-held) debt; some of those countries are both frequent IMF customers and known to quickly forget the promises made at the time their lending programs were concluded, spelling financial trouble. The United States and other Group of Seven (G7) countries, as the main creditors of the IMF, have the most to lose if the institution continues to extend loans that put its own balance sheet at risk.

The IMF will also need to sharpen its policy messages. Its role in economic surveillance has moved to the background in recent years, although its reports and pieces on geopolitical fragmentation (including the semi-annual World Economic Outlook) still attract interest. But the policy conclusions in those reports and policies often disappoint. For example, a recent blog post downplayed the impact that Chinese subsidies and trade practices have on strategic sectors and how those practices would provide China with advantages in a further intensification of geopolitical tensions.

The IMF’s main shareholders should therefore use the Annual Meetings to lean on the IMF to refocus its resources on where they could be most useful at this time—freeing up its excellent staff to analyze economic trends and develop useful policy solutions in an environment of geopolitical rivalry. Democratic countries around the world need its work and its independent voice more than ever.

SEPTEMBER 24, 2024 | 9:57 AM ET

The IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings in 2024: Five important issues to be addressed