The coup in Myanmar is an early test of the extent to which the Biden administration will respond to an authoritarian reversal of democracy abroad. And it’s one that authoritarian governments around the world will be watching closely—China, to understand the implications for its repressive actions against the Uighurs and in Hong Kong; Russia, to assess the consequences for its jailing of dissident Alexei Navalny and suppression of demonstrations at home and in Belarus; and North Korea, to grasp how the new US administration will address Pyongyang’s human-rights abuses.

Washington’s initial response to the military takeover in Myanmar was swift. Under a new executive order, the White House gave itself broad authorities and adopted strong sanctions against those behind the coup. It should follow up with a more comprehensive policy that includes the administration calling the military’s persecution of the country’s Rohingya minority in 2017 what it is: genocide. The United Nations and human-rights groups have described the crimes against the Rohingya as such. But US economic leverage to respond to such grave acts is limited; after opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest and her party won elections in 2015, the Obama administration prematurely terminated its core sanctions program against the country a year later.

The Biden administration’s announcement that it will freeze one billion dollars of Myanmar government funds held in US banks will squeeze military leaders. But sanctions cannot be the only tool that the United States deploys. The response should also include taking a robust, coordinated approach with allies on human-rights issues while putting pressure on China, Myanmar’s largest trading partner and investor. A comprehensive policy should include the following:

Sanctions: In addition to redesignating military leaders in Myanmar sanctioned by the Trump administration in 2019, the Biden administration sanctioned additional military officials involved in the coup and three companies with ties to the military. If the military in Myanmar does not respond to these initial moves, the Biden administration should prepare to re-impose sanctions terminated under the Obama administration and target military-controlled enterprises such as Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC), a secretive military enterprise that operates strategic sectors such as ports and telecommunications, and Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL), another secretive military enterprise that compels foreign investors to partner with it in lucrative sectors such as tobacco. This would include barring any future investment in or business transactions with MEC and MEHL, including unwinding any existing ventures. Sanctions should also involve re-imposing sanctions on North Korea-related targets, given prior military-to-military engagement between the two countries. The administration should also re-invoke JADE Act sanctions authorities, which prohibit the import of jadeite and ruby originating in Myanmar, a restriction also lifted in 2016.

Human rights: The administration should call the military’s abuses against the Rohingya what they are: genocide. The administration may also consider designations of human-rights abuses under the Global Magnitsky Act if pressed to do so by Congress, which would send a clear message to Myanmar that the US government will not tolerate human-rights violations. But it would be harder to unwind these designations should military leaders in Myanmar take appropriate steps toward a resolution of the democratic crisis. The Biden administration should also develop a plan to aid Rohingya refugees and provide them with humanitarian assistance.

Releasing political prisoners: Washington should continue working with allies to call for the release of all political prisoners in Myanmar—not only Suu Kyi but all members of her party, the National League for Democracy.

Diplomacy: One key to success is for the US to enlist Japan, India, and Singapore, all top foreign investors in Myanmar, in its efforts to respond to the coup. The Biden administration should also work with the United Kingdom—the drafter of a UN Security Council statement condemning the coup in Myanmar—and the European Union to press for more robust language calling the violence against the Rohingya genocide. The Chinese government, which has ties to Myanmar’s military, will likely try to water down the language in the resolution. The United States and its allies should call on Beijing to join its response to the coup, even if nothing comes of it. Doing so would put pressure on China to illustrate what kind of role it will play on international issues and crises as its economy and military advance over the next decade.

Limiting Myanmar military involvement: Washington should continue to encourage responsible investment in Myanmar. But it should also call on all international companies to break ties with military-linked enterprises such as MEC and MEHL, which are woven into the political fabric of the country and have been involved in human-rights abuses, land-grabs, and corruption for decades.

The current military-civilian power-sharing arrangement under the Myanmar constitution, where a quarter of the seats in parliament are reserved for military officials, complicates efforts toward a peaceful resolution in the country, but such an outcome is not impossible. Myanmar was making progress toward democracy when the military recognized Suu Kyi as the de-facto head of government and started scaling back violence against the Rohingya minority, but the United States made a critical mistake by lifting sanctions and pressure on the military too early. There is still a window to work with allies and identify targeted pressure points that incentivize a resolution between the country’s political and military leadership. This approach would have the added benefit of signaling to others watching around the world how exactly the Biden administration plans to protect freedom and human rights.

Andrea R. Mihailescu is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center. She is currently teaching courses on international relations at Pepperdine University’s School of Public Policy while on sabbatical from the US Department of State, where she last was a member of the secretary’s Policy Planning staff working on sanctions and CFIUS issues. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the State Department or any other agency.

Further reading

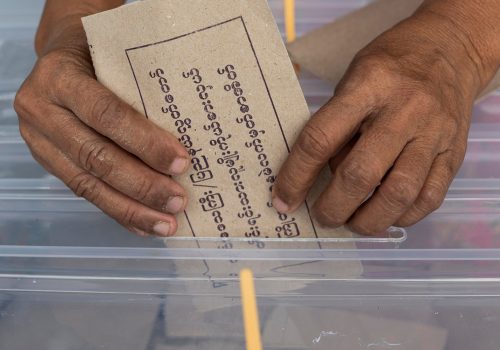

Image: A demonstrator is detained by police officers during a protest against the military coup in Mawlamyine, Myanmar February 12, 2021. Than Lwin Times/Handout via REUTERS