FAST THINKING: A coup in Myanmar

JUST IN

Not long ago, Myanmar was heralded as a case for optimism in Southeast Asia as it embarked on a transition to democracy after decades of military rule. But last night it suffered a coup. The military is back in control after detaining Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, the country’s de facto civilian leader, and senior members of her ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) party. Civil-rights activists have been detained as well. How did this happen?

TODAY’S EXPERT REACTION COURTESY OF

- Rudabeh Shahid (@RudabehS): Nonresident Senior Fellow at the South Asia Center

A slow but steady build-up to the coup

- This did not come out of nowhere, Rudabeh tells us. Despite its recent move toward democracy, Myanmar still struggled with weak democratic norms and institutions. The constitution that the country ratified in 2008 “allows the military to take power during a state of emergency,” she notes, and reserves 25 percent of parliamentary seats for the military, “including key portfolios such as defense and foreign affairs.” The military has now exploited these lingering powers, declaring a one-year state of emergency to seize control of the government.

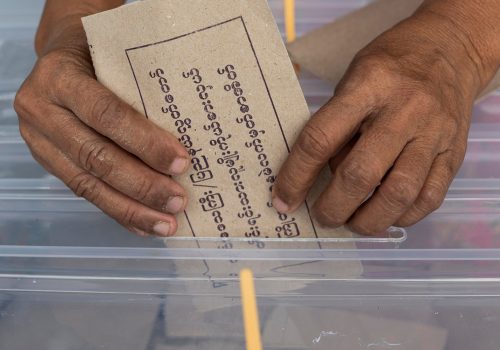

- Military leadership, Rudabeh adds, grew nervous following national elections in November that resulted in a landslide victory by Suu Kyi’s NLD, interpreting the outcome “as a threat to its authority.” These elections were beset by many problems, including the cancellation of polling in several ethnic-minority states and the disqualification of candidates based on ethnicity, she notes. And the military is now seizing on irregularities to undermine the result by claiming that there was widespread fraud.

- But perhaps the most important factor in all of this is the ongoing persecution of the Rohingya ethnic minority in the country’s west—which under the NLD’s watch in 2017 devolved into ethnic cleansing and possible genocide at the hands of the military. Rather than defend the Rohingya against these abuses, Rudabeh notes, Suu Kyi and her party backed the generals—even at one point going to the International Court of Justice to defend the military’s actions. While this may have helped Suu Kyi’s image at home, particularly among the Bamar Buddhist majority, it badly tarnished the reputation of the one-time human-rights icon abroad.

- One condition for staging “a successful coup is to have a degree of public support,” Rudabeh notes. “After decades of losing credibility among the masses, the Myanmar military in recent years has tried to find ways to grow its support among its citizens. Suu Kyi allowed herself to be used as a tool of the military—not least by condoning the latter’s treatment of ethnic minorities.”

- The military was further aided, she adds, by the muted international response to the persecution. “Nations across the world have largely remained silent on the possible genocide against the Rohingya,” she says, and this “emboldened Myanmar’s military” to now engage in authoritarian practices against the country’s elected leadership.

Subscribe to Fast Thinking email alerts

Sign up to receive rapid insight in your inbox from Atlantic Council experts on global events as they unfold.

What can the international community do?

- While many Western nations and Myanmar’s neighbors have expressed concerns about the moves to undermine the country’s nascent democracy, with US Secretary of State Tony Blinken calling on the military to “reverse these actions immediately,” that’s not likely to make much of a difference. Rudabeh predicts that the military, having learned from the response to its campaign against the Rohingya that it could act with impunity, “will not back down” even if it faces more economic sanctions.

- If sanctions are imposed, she advises, they should distinguish between Myanmar’s people and military and be targeted toward the latter as part of an effort to pressure the military into restoring NLD leaders to their offices.

- But “the roots of the crisis are in the constitution,” she cautions, and international actors should therefore focus on “pushing for a constitution that guarantees free speech and citizenship for all residents of Myanmar” while reducing “the power of the military.” Doing so requires establishing a constitutional committee. “Unlike last time,” Rudabeh notes, “the military should not be allowed to frame the country’s constitution.”

Further reading

Thu, Jan 7, 2021

South Asia: The road ahead in 2021

Feature By

The shadow of 2020 is likely to loom large over the coming year for South Asia, which faces unprecedented economic challenges, deterioration of democratic norms and institutions, and the existential threat of climate change.

Mon, Dec 7, 2020

FAST THINKING: The next stage of Venezuela’s power struggle

Fast Thinking By

The Trump administration recognized opposition figure Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s interim president and mobilized nations around the world to do the same. But Nicolás Maduro is still in power—and perhaps even more entrenched after winning control this weekend of the National Assembly in an election boycotted by Guaidó and his allies. What does the election mean for the opposition’s future?

Fri, Nov 6, 2020

A zero-sum game: What can we expect during the upcoming elections in Myanmar?

New Atlanticist By Rudabeh Shahid

While Myanmar gained attention for the restoration of some democratic rights in 2010 following years of military rule, the upcoming election is at risk of undermining this progress amid widespread political repression and human rights violations. There is strong evidence that the elections will be neither free, fair, nor inclusive, as a result of the suppression of free speech, use of hate speech, and cancellation of voting in several regions.

Image: Myanmar's military checkpoint is seen on the way to the congress compound in Naypyitaw, Myanmar, February 1, 2021. REUTERS/Stringer