South Asia: The road ahead in 2021

Introduction

By Irfan Nooruddin

At long last, the year that seemed like it might never end is in the history books. While the record-breaking development of multiple safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines is grounds for optimism that 2021 will be better—admittedly a very low bar after the year just completed—the shadow of 2020 is likely to loom large over the coming year for South Asia, which faces unprecedented economic challenges, deterioration of democratic norms and institutions, and the existential threat of climate change. Those challenges are hardly new, of course, but the last year starkly revealed just how unprepared and unable South Asia’s governments were to tackle them, causing tremendous suffering and distress for its almost two billion residents. Across South Asia’s capitals, intense scrutiny will be trained on Washington, DC to see how President-elect Joe Biden’s administration approaches the region. Will the United States advance more meaningful engagement with South Asia on its own terms, will its strategy be shaped by a narrower desire to counter China’s growing power, or will a United States traumatized by the pandemic and its brush with authoritarianism turn inward to heal its wounds? Chastened by 2020, a year we honestly confess we did not see coming, we do not pretend to know the answers to these questions, though we can say this: For South Asia’s almost two billion people, the need for humane, capable governance—domestic, regional, and global—is immediate and imperative. The year 2020 made clear that politics as usual are not good enough; the onus on the political class is to show that it can redeem itself in 2021.

Click here to read the South Asia Center’s 2020 midyear update on these governance issues and more.

Jump to a country:

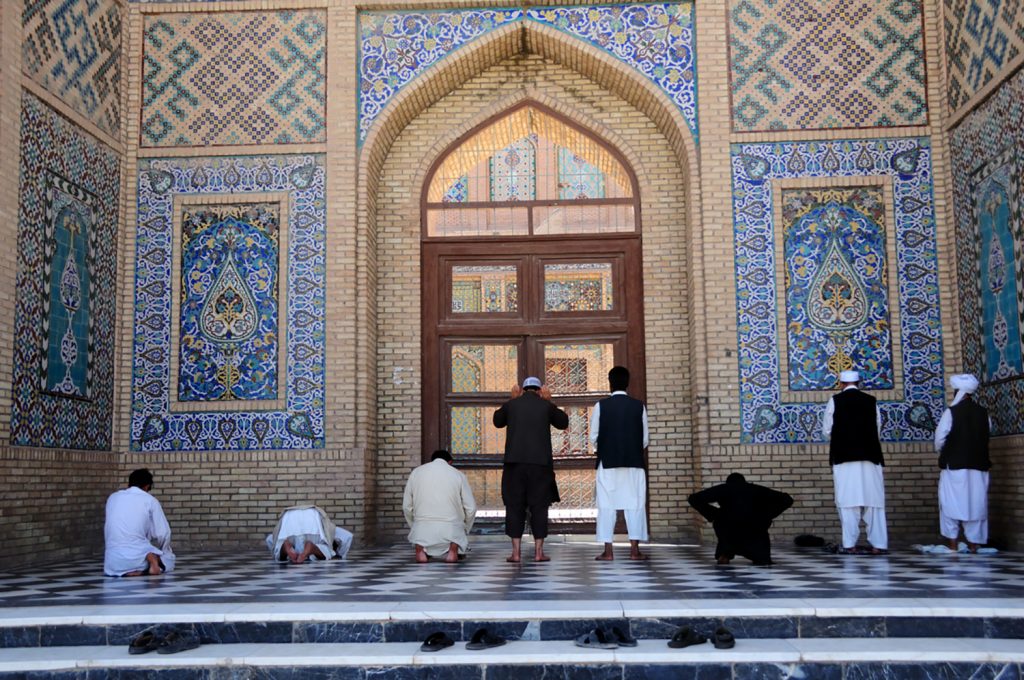

Afghanistan

By Harris Samad

That Afghanistan faces challenges as it enters 2021 is hardly new, but the political and security landscape that Afghan President Ashraf Ghani must contend with is arguably more different than it has been at any point in the last two decades. Most immediately, the uncertain outcomes of the ongoing Afghan peace talks in Doha raise thorny questions about the durability of a potential peace agreement. Three elements in this respect are worth focusing on: Afghan youth, who represent a significant generational shift from elites leading the peace process and whose buy-ins are, thus, needed for the negotiations to succeed; the future of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) in the context of a potential US military withdrawal; and attaining transitional justice for crimes committed by all parties—including international stakeholders—during decades of war. Beyond the peace negotiations and security landscape, two challenges in particular deserve more attention than they typically receive: addressing energy shortages, which is vital to lifting millions of Afghans out of poverty, and air pollution, which continues to be a silent, but wicked, killer in Afghanistan’s cities.

A powerful generational shift: The last twenty years of war in Afghanistan have seen the growth of a new generation of Afghans. Like their parents before them, many have only known their country in wartime, but unlike older generations, today’s young Afghans have grown up with an interconnected world on Twitter, Instagram, and other digital media. As such, the generational divide between Afghan youth and those negotiating their future in Doha is enormous. Given that these political elites are negotiating a deal with consequences that their children and grandchildren will inherit, the importance of youth buy-in on a prospective peace deal is vital for the deal’s legitimacy—and cannot be understated. An agreement that does not have the support of Afghanistan’s young people is unlikely to last. It is, thus, crucial that the negotiations do not ignore the necessity of buy-in by young Afghans upon whose shoulders the peace process’s long-term implementation will come to rest.

The future of the ANDSF: Afghanistan’s history is marked by foreign intervention, subsequent pullout, and some form of domestic military force adapting to, and surviving, this highly fluid environment. Should the United States—as President Donald J. Trump has demanded—make an abrupt drawdown in January without provisions for continued support of the ANDSF, Afghanistan could return to civil war. Whether the ANDSF will survive this in its current form or shift to a different one remains unknown, but the Taliban hold more ground now than at any point since 2001, and the precariousness of the situation demands careful and calculated adjustments to the Afghan security sector. Whether the Trump administration will engage in such sledgehammer diplomacy just before leaving office—tremendously complicating the future of the ANDSF and a prospective peace deal—will shape much of 2021 for Afghanistan.

Given that… political elites are negotiating a [peace] deal [in Doha] with consequences that their children and grandchildren will inherit, the importance of youth buy-in on a prospective peace deal is vital for the deal’s legitimacy.

Transitional justice for crimes committed during the war: Addressing human-rights violations and crimes by all parties during decades of war in Afghanistan is crucial. In addition to well-documented violations committed unilaterally by the main domestic stakeholders, members of the international community have committed similarly heinous crimes throughout the war. In December of last year, the BBC reported a 330-percent rise in the killing of Afghan civilians by joint US-Kabul airstrikes since 2017, as well as the growth of an “unchecked warrior culture” among Australian soldiers, embodied by perpetrators’ fetishization of the murder of Afghan prisoners. International power dynamics between the West and South Asia mean that non-Afghan perpetrators are likely to get off lighter than their Afghan counterparts, but the importance of the work of the High Council for National Reconciliation of Afghanistan—leading a process of nationwide healing after decades of war—cannot be understated.

Energy: Though Afghanistan continues to have significant energy shortages—with power cuts regularly disrupting life for Afghans at work and in school—investments and projects in this sector are working toward a solution. A $110-million project by the Asian Development Bank announced in September of last year “will finance the construction of 201 kilometers of a 500-kilovolt overhead transmission line from the Surkhan substation in Uzbekistan to the Khwaja-Alwan substation in Afghanistan—a key interconnection node.” The finished project will provide power to five hundred thousand new households. Similarly, an ongoing wind-farm project in Herat, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), is targeted to be operational in 2022. It will use wind power to generate twenty-five megawatts of electricity supporting the energy requirements of approximately three hundred thousand Afghans and businesses. Despite major challenges, these and other projects signal an increasing interest by Kabul, investors, and the international community in supporting sustainable, long-term solutions to Afghanistan’s energy needs, representing a crucial sector to watch in 2021.

Air pollution: Dirty air continues to be a silent killer in Afghanistan’s cities. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that household air pollution (HAP) kills more than twenty-seven thousand Afghans per year. Traditional gender roles that relegate women and girls to the home make them even more at risk from HAP than Afghan men. Electrical generators using poor-quality fuel, burning of garbage and rubber, and older motor vehicles that emit stronger emissions are also among the many factors compromising Afghans’ health in cities. However, progress is being made to combat this deadly problem; by 2015, the introduction of liquid petroleum gas had reduced the number of automobiles burning petroleum by approximately 30 percent, and “most bakeries in Kabul have switched from wood to natural gas for their ovens.” In early 2020, Ghani issued decrees that require heating systems to be equipped with smoke purifiers and banned burning rubber and plastic for fuel. Additional advancements in electricity access—which will address unreliable energy access as a major underlying reason for burning tires, garbage, and similar fuels—are necessary to support cleaner air.

Bangladesh

By Kaveri Sarkar

The havoc wrought by COVID-19 revealed preexisting cleavages and challenges that will dominate much of 2021 for Bangladesh. The country must tackle the imminent threat of climate change; undertake a vaccination drive that includes its most vulnerable, while utilizing poor health infrastructure in one of the world’s most densely populated countries; recharge its export- and labor-oriented economy; and provide economic security to communities, including garment workers and Rohingya refugees, all while battling religious extremism and government censorship.

A drastic reduction in the free flow of labor and goods, catalyzed by COVID-19, has harmed Bangladeshis at home and abroad: The Bangladeshi government provided an $8-billion stimulus to its export-oriented industries to make up for the heavy billion-dollar losses on remittances, orders, and exports. But the female-dominated garment workforce and migrant laborers were left to their own devices to deal with the worst consequences of the lockdown. Not only did Bangladesh’s economy take a heavy blow when remittances—one of its two biggest sources of revenue—dropped significantly, but its migrant workers simultaneously faced job losses in the Gulf and repatriation enforcements as countries closed their borders.

While migrant workers battled with poverty and government neglect, garment workers also struggled. Bangladesh is the world’s second-largest exporter of textiles, accounting for 84 percent of total exports comprising ready-made garments. Garment workers in Bangladesh dealing with poor working conditions and low pay saw COVID-19 deepen their plight. Shutdown of factories caused widespread unemployment in this sector, pushing workers to the brink of poverty and starvation. As factories reopened, some garment workers returned to work while others continue to fight hunger, poverty, and joblessness; Bangladesh’s vaccination drive must prioritize these two groups. As Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government attempts to reconstruct the economy in 2021, it must not forget those vulnerable workers on whose backs Bangladesh’s recent growth miracle is built.

A forgotten crisis: The plight of the Rohingya people: The pandemic and other competing global headlines rendered forgotten the plight of the one million Rohingya refugees seeking asylum in Bangladesh from the threat of persecution in Myanmar. In addition to high virus case counts in overflowing refugee campus, the treatment of Rohingyas had a gendered impact, with instances of child marriage, child poverty, and human trafficking in the camps. The end of 2020 brought no relief with the relocation of Rohingya refugees from Cox’s Bazar to Bhasan Char, an island which experts believe is not suitable for human habitation. Antithetical to the government’s claims of a consensual relocation, Rohingyas described their move to Bhasan Char as forced and unsafe, as they are driven onto over-congested boats. The fatal implications of this forced resettlement will likely be clear in 2021, and will pose a fundamental question: Which state, or international or regional community, is able and willing to tend to this crisis—and, more importantly, how?

As Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government attempts to reconstruct the economy in 2021, it must not forget those vulnerable workers on whose backs Bangladesh’s recent growth miracle is built.

A tug of war in society: Against the background of a humanitarian crisis and a tumultuous economy, the end of 2020 witnessed a row over the installation of sculptures that religious leaders in Bangladesh opposed—underlining the prevalence of religion in politics and the contention between Islam and art representation. Furthermore, the arrest of a cartoonist who espoused an anti-government stance, along with other grave instances of media censorship and crackdowns on dissent in Bangladesh, show that personal liberties have been increasingly threatened since the introduction of the ominous Digital Security Act two years ago. The government has conveniently cast any criticism toward its policies as misinformation, further suppressing and punishing freedom of expression.

Another instance of the gap between policymakers and civil society was the government’s adoption of the death penalty for rape after a gang-rape case sparked protests and public outcry. As critics pointed out, the imposition of the death penalty was a means for the government to placate the demonstrations based on a 150-year-old colonial definition of rape, while allowing harassment of garment workers and marital rape to continue unadministered and without addressing the root causes and stigma upholding the patriarchal structure of society.

The threat of climate change propels Bangladesh to take a key role on the international stage: Hasina has routinely rallied the efforts for international cooperation toward mitigating climate change. Bangladesh, a country that is projected to face devastating effects from climate change—and already grapples with cyclones and rising sea levels—has no choice but to continue leading efforts to build international consensus on the reduction of fuel emissions and on increased financial support for the country’s climate-change-mitigation efforts. US overtures to Bangladesh as a cushion against China offer Dhaka the leverage to secure the technological know-how and financial support it requires to innovate toward a greener economy. Bangladesh cannot be a lone wolf in the fight against climate change; it must secure allies that can assist the vulnerable country in its efforts.

Bhutan

By Harris Samad

The COVID-19 pandemic is forcing the Kingdom of Bhutan’s tourism-reliant economy to revolutionize and adapt to the socially distanced age, setting a possible example for other tourism-dependent economies in 2021. The Kingdom is also broadening its engagement with the international community diplomatically, signaling a shift in historical policies that minimize foreign engagement. Finally, the decriminalization of “unnatural sex” in Bhutan’s penal code—interpreted by many as the effective legalization of homosexuality—makes it the latest country in Asia to roll back long-standing restrictions on sexuality. The Kingdom thus enters 2021 with cautious, but significant, momentum on multiple fronts.

Adapting tourism to the COVID-19 world: Bhutan’s tourism sector was a major economic driver before COVID-19 and, like many tourist-dependent economies, the Kingdom abruptly halted tourists from entering the country last year in the hope of minimizing the virus’s spread. However, Thimphu is looking toward the future to adapt and revolutionize COVID-friendly tourism. The Tourism Council of Bhutan and the country’s Ministry of Health are currently evaluating a proposed “Travel Bubble” that permits tourists to enter, but with two options for ensuring that, should they have it, they will not transmit COVID-19 to locals.

The first is a mandatory quarantine period with multiple COVID-19 tests and “wellness” activities, followed by isolated and pre-scheduled travel. If visitors then test negative for COVID-19 again after fourteen days in Bhutan, they are permitted increased access to the country and interactions with locals. The second option is a mandatory COVID-19 test with no quarantine upon entering the country, but tourists are then required to stick to special trekking programs and have no contact with locals. Such innovations serve as an example for reconceptualizing tourists’ experiences in a socially distanced world and can inform similar efforts by other tourism-dependent economies hit hard by the pandemic. For this reason, Bhutan’s innovative approach to COVID-friendly tourism is a key sector to watch this year.

An increasing presence on the global stage: Bhutan’s historical isolation from the international community continues to ebb as it cautiously opens diplomatic engagement with a handful of countries. At the end of last year, Thimphu established diplomatic relations with Israel, making Israel one of only fifty-five countries to have such relations with Bhutan. Prior to Israel, Bhutan’s most recent diplomatic normalization was with Germany in November of last year and, before that, Oman in 2013. Thimphu only approved the use of the Internet and television in 1999, but an explosion of social media usage among young Bhutanese, and the gradual opening of diplomatic relations with more countries, suggests that the Kingdom’s engagement with the world is accelerating into 2021.

[Bhutan’s] innovations serve as an example for reconceptualizing tourist experiences in a socially distanced world.

Sexual-orientation rights: The legalization of homosexuality (characterized as “unnatural sex” in Bhutan’s penal code) has been in the works for quite some time in the Kingdom, with its lower house of parliament approving the move in June 2019. The subsequent approval by the upper house of parliament in December of last year was hailed by Human Rights Watch. Though the final approval lies with King of Bhutan Jigme Wangchuck before this reform becomes codified into law, these developments reflect a welcome progression in attitudes toward sexuality in the Kingdom and give hope to sexual as well as ethnic and religious minorities living in Bhutan. That said, whether this revision receives royal approval, and paves the way for further changes in Bhutan’s human-rights landscape, remains to be seen.

India

By Kaveri Sarkar and Shashank Jejurikar

India has had one of its most difficult years since independence. A painful economic contraction, bloody border skirmishes with China, the deepening of sectarian divisions, and the weakening of secular democracy have all taken a heavy toll on the country. Each of these challenges poses a dire threat to India’s long-term prosperity and future global influence. The Indian government’s ability to address the country’s concurrent economic and geopolitical shocks in 2021, as well as its willingness to reverse its own damaging social policies, will define the country’s future.

Emerging from COVID-19 and addressing an economy in crisis: The human cost of the COVID-19 pandemic in India cannot be overstated. With 140,000 Indians dead per official statistics and almost ten million infected so far, the virus has taken a terrible toll. As we enter 2021, India must grapple with the enormous logistical challenge of vaccinating its 1.3 billion people. India’s existing vaccine-distribution network, though it has been successful in vaccinating children against polio and other diseases, will be strained severely to achieve vaccination of the entire population against COVID-19. Ensuring that vaccines are administered in a comprehensive and timely manner will require an expansion of India’s health infrastructure and close cooperation between municipalities, states, and the central government. A successful rollout of the coronavirus vaccine (whose development and production have been supported, in large part, by Indian manufacturing and expertise) is critical to India’s fight against the pandemic.

Even when the country emerges from COVID-19, it will still face the monumental challenge of rebuilding its devastated economy. The once-roaring economy entered 2020 in an already precarious position: consumer sentiment had fallen dramatically, gross domestic product (GDP) growth had almost halved in the span of a year to 4.5 percent, and unemployment had reached a four-decade high. This weak economy left India unprepared to withstand the shock of the COVID-19 lockdown imposed on the country in April. The effects of this lockdown, which was hastily announced and ill-planned, have been catastrophic. Workers in India’s industrial hubs lost their incomes almost overnight as unemployment soared. Industrial production also collapsed: the country’s Purchasing Managers Index, an economic gauge for manufacturing activity, reached a shocking low of 27.4 in April, though it has recovered since.

Navigating these economic headwinds will be vital to ensuring India’s stature in the world as it prepares to assume the presidency of the Group of Twenty (G20), and to securing prosperity for its people. In particular, India should focus on alleviating the hardship of its most vulnerable citizens, who have been the most adversely impacted by the COVID-19 and economic crises of 2020.

Expectations that the incoming [Biden] administration will hold Modi’s government accountable for human-rights abuses are unrealistic.

Vulnerable communities disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 and the economic crisis faced struggles—will 2021 bring respite?: Though the pandemic and its economic fallout have harmed India as a whole, they have inflicted particularly brutal pain on India’s most vulnerable people: poor laborers, children, women, and Dalits.

The most visible of these groups in 2020 has been India’s low-income workers. A large portion of the country’s workforce consists of some forty million internal migrants from the country’s poorest states, such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. In recent years, these migrants have left their homes to pursue higher wages, often in dangerous and risky work near urban centers. When the government imposed its lockdown, these workers were left to fend for themselves. Suddenly without employment, millions embarked on a long, and often deadly, exodus to their home villages (sometimes bringing COVID-19 with them), where many remain today. Although urban industrial activity is now returning, India’s migrant workers have not recovered from the financial and psychological trauma of their ordeal.

In addition to migrant workers, many other vulnerable groups have been disproportionately harmed in 2020. A horrific rape case highlighted the struggle of Dalit women in India, as well as the intersection of gender and caste that furthers their marginalization. Children of poor households also suffered, often forced to sacrifice their education and enter into angerous labor. Farmers, too, made their plight known, taking to the streets of Delhi in protest against the three new farm laws passed by the Indian government, which they believe would leave them at the mercy of wealthy corporations. The Indian government’s willingness in 2021 to make support available for its most vulnerable and disillusioned citizens will be crucial in alleviating the struggles of those people.

The year that took Hindu nationalism and majoritarianism to new heights: After 2019 ended with nationwide protests against the new citizenship laws criticized for deepening sectarian cleavages, 2020 only solidified the communal political rhetoric advanced in the country. The year began with a grave attack by affiliates of the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) on students and faculty at the liberal Jawaharlal Nehru University who were protesting against the 2019 citizenship amendments and fee hikes. The next month witnessed the Delhi riots of 2020, in which violence against Muslims reached new heights against a backdrop of Trump’s gaudy visit to India. With the police standing by, and even abetting Hindu-nationalist goons in some cases, crackdown on peaceful protestors and incitement of mob violence in these two incidents cast unease over India’s democratic and secular ideals.

Concerningly, the rhetoric adopted by the BJP espouses an exclusive brand of nationalism; it strives to appeal to its vote bank of upper-caste Hindus by increasingly projecting the Muslim population as “the other” and a security threat to a supposed Hindu nation. In this shifting political and ideological landscape, India is inching toward authoritarianism. With a hike in media censorship, the standstill of amnesty operations, detainment of activists, misinformation campaigns, and multiple vehement crackdowns on peaceful protests, free speech and democratic rights are in danger. Arming the government with legal and judicial backing to further legitimize its nationalistic agenda, the Supreme Court in a 2020 case exonerated BJP leaders involved in the Babri Masjid demolition of 1992, as well as a recent Love-Jihad law in the populous state of Uttar Pradesh that seeks to delegitimize interfaith marriages.

Although Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi fostered an uncritical personal relationship, some analysts anticipate that Modi’s government will receive more criticism for its human-rights record from the new Biden administration. Given the convergence of interests between the United States and India, however, expectations that the incoming administration will hold Modi’s government accountable for human-rights abuses are unrealistic, as the shift in the stances of Biden and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris over time toward Kashmir have shown.

A changing defense and geopolitical landscape: As India struggled to meet an unprecedented series of challenges on its homefront, it was forced to also deal with external threats. In June, Indian and Chinese soldiers engaged in a bloody brawl along their mountainous eastern border, resulting in the deaths of twenty Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of Chinese soldiers. This deadly episode, the first record of fatalities in an Indo-Chinese clash in more than forty-five years, came in response to China’s expansionist encroachment on India’s side of the Line of Actual Control. Following the incident, both countries moved a substantial number of troops and supplies to the disputed border. Though there have been a number of diplomatic talks between the two countries, none of these have addressed the underlying dispute over where the border actually lies. Until this dispute is formally settled, military disengagement will remain elusive.

The precarious situation with China—which led to a massive anti-China backlash among India’s people and government—has accelerated India’s already-deepening defense and strategic partnership with the United States. In October, the two countries signed an information-sharing agreement to boost the accuracy of India’s drones and missiles. This came shortly after a successful meeting of the “Quad,” an informal multilateral defense partnership between the United States, India, Japan, and Australia. An increasingly powerful and assertive China that challenges the interests of both the United States and India has acted as a catalyst for this increased partnership. While continuing defense cooperation between India and the United States is all but assured, non-military cooperation is less so. Much work has been done to lay the foundation of a free-trade agreement, and though prospects for such an agreement are good, it will take committed engagement and compromise for India and the United States to set aside disagreements and make it a reality.

To preserve and promote its global standing, India must also reinvest in its regional partners. Growing economic cooperation with the Maldives and Bangladesh amid the pandemic was a promising sign, whereas border disputes with Nepal revealed continuing challenges. If India fails to shore up relations with its South Asian neighbors, it risks those countries drifting closer to China, as Pakistan and Sri Lanka already have.

The Maldives

By Shashank Jejurikar

In 2020, the Maldives grappled with geopolitical shifts, the pandemic, and an economic collapse. Maldivian President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih of the Maldives Democrat Party (MDP), who ousted his authoritarian predecessor in 2018, has maintained strong support and a parliamentary supermajority throughout all these challenges. His government’s ability in 2021 to resuscitate the flagging economy, build diplomatic ties with global and regional powers, and manage the climate catastrophe will define the country’s future.

The COVID-19 pandemic has crushed the Maldives’ tourism-dependent economy: Tourism has been the beating heart of the Maldives’ economy for years, with the country’s scenic islands and beaches attracting visitors from all around the world. As a result of the travel restrictions and lockdowns imposed worldwide in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, the Maldivian economy has contracted significantly, with some economists even fearing for the country’s food security. To get through this crisis, the country opened its borders in a desperate bid for tourism and secured an emergency loan from India. Though the Maldivian tourism industry will recover, the country must diversify its economy in the long term in order to make itself more resilient to future exogenous shocks.

The country must diversify its economy in the long term in order to make itself more resilient to future exogenous shocks.

Renewing ties with the United States, and managing relationships with India and China: As the Indo-Pacific has increasingly become a geopolitical flashpoint, global and regional powers like the United States, China, and India have increased their engagement with the Maldives. To increase its influence in the Indian Ocean to counter China, the United States in October formalized its ties with the Maldives, opening its first-ever embassy in the country. India, too, has increased engagement with the Maldives, particularly in the realm of defense.

The development of closer ties with India and the United States represents a shift from the policy of former Maldivian President Abdulla Yameen, the ousted autocratic leader, who avidly courted China. China’s influence over the Maldives persists, however, most explicitly in the form of hundreds of millions of dollars in outstanding loans that were issued to the Maldives as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Though these loans funded large infrastructure projects that boosted the economy in the short run, the Maldives’ struggles to repay them leave the country vulnerable to falling into a debt trap with China. Servicing these debts sustainably, and maintaining financial independence from China, must be a priority for the Maldivian government in 2021.

The climate catastrophe continues to loom over the Maldives: As an island nation, the Maldives is immediately vulnerable to rising sea levels that threaten the country’s economy and territorial integrity. Solih’s political ally Mohamed Nasheed has been a long-standing and forceful advocate of combating climate change, and in his role as speaker of parliament has continued to advocate for a more climate-conscious agenda. On the international stage, Solih spoke to the United Nations in 2020 on the goals his country has set, while arguing for a global sustainability agenda. Given the Maldives’ dependence on the rest of the world to combat the climate change that drives rising sea levels, international cooperation is crucial. The country must build on its existing partnerships with major economies like the European Union, and continue to be a global advocate for sustainability.

Nepal

By Capucine Querenet

Subsequent to the tumultuous first half of 2020, Nepal continues to face headwinds generated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Gross underplaying of ground realities, exacerbated by flagrant mismanagement of the crisis, brought simmering tensions to a boiling point as protests erupted across Kathmandu, and the ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP) confronted perennial intra-party fissures. Beyond Nepal’s massive governance crisis, the virus onslaught continues to ravage the country’s economy and threatens to worsen the marginalization of vulnerable populations. As Nepal tends its wounds, leadership must proceed with caution vis-à-vis the increasingly belligerent Sino-Indian rivalry; the slightest diplomatic blunder could jeopardize Nepal’s post-COVID reconstruction and precipitate a geopolitical shift in the region.

To be or not to be: the NCP’s insoluble dilemma: Party unity within the NCP is severely strained and may arguably be the country’s biggest obstacle to tackling the pandemic effectively. Tensions between Nepali Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli and Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal have long been fractious, but calls for Oli’s resignation at the end of June sparked a flurry of ineffectual political maneuvers at the expense of COVID-19 relief efforts. As of early December, both factions have failed to break the impasse. While demands for Oli’s resignation endure—despite mediation efforts by a six-member task force—a party split threatens to jeopardize the NCP’s progressive agenda and communist movement, let alone its prospects for reelection.

Even so, the devastation of COVID-19 remains a greater detriment to the party’s image. Since early June, dissatisfied citizens have flooded the streets of Kathmandu in a nonviolent bid to better the current, weak response, only to clash with riot police; by mid-December, hundreds were calling for the restoration of the monarchy and a Hindu state. Continued political infighting will only further public disillusionment with the ruling party and heavily cripple Nepal, undermining previously projected growth, and undoubtedly pushing more Nepalis below the poverty line. While the country’s future and that of the NCP remain uncertain, the Nepali people have spoken with clarity—it’s high time the government responds.

The slightest diplomatic blunder [in the Sino-Indian rivalry] could jeopardize Nepal’s post-COVID reconstruction and precipitate a geopolitical shift in the region.

A new battleground for China and India: Domestic uncertainty is compounded by continued efforts by India and China to vie for influence in Nepal. Recent high-profile ambassadorial visits from both rising giants foreshadow shifting geopolitics for the greater South Asia region and threaten Nepal’s neutrality and non-alignment intentions. Nonetheless, carefully balancing ties between both countries will yield benefits. The latest visit by Chinese Defense Minister and State Councilor Wei Fenghe primarily focused on further development of the Belt and Road Initiative and boosting military ties. Continued involvement in the multi-billion-dollar project could prove crucial to catalyzing Nepal’s ascent to middle-income-country status by granting greater connectivity, notably via economic integration and the construction of critical energy and transport infrastructure.

Across the country, India-Nepal ties have focused on remediating the relationship, subsequent to a border controversy in June. Three 2020 visits by Indian officials culminated in renewed acknowledgment of both countries’ deep-seated historical ties and progress on bilateral cooperation projects. Improvement of this relationship is key for Nepal on many fronts, most notably the economy: India accounts for more than 30 percent of Nepal’s foreign direct investment; the Nepali rupee is pegged to India’s; and more than six million Nepalis work across the border, among other dependencies. Thus, considering the pandemic and ensuing vaccine diplomacy, Nepal should continue to maintain healthy relations with both its neighbors. However, the country cannot successfully flex its diplomatic muscles without some semblance of political stability. Alas, this does not appear to be in Nepal’s cards anytime soon.

Pakistan

By Azeem Khan

The coming year in Pakistan will be dominated by the question of whether the current government will see out the year. The eleven-party opposition alliance against Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan is expected to continue in the new year, especially if lockdown restrictions are eventually eased. The outcome will depend on a few factors such as the happiness of the security establishment with the civilian government, the success of the government in curbing rampant inflation, and the overall economic recovery following the pandemic, which the government must engineer while heeding stringent International Monetary Fund (IMF) restraints. Around this tumult, the civilian government will be tempted to impose curbs on press and Internet freedom. Upheaval—or, rather, a shift—is also expected in Pakistan’s foreign relations as it increasingly moves away from its dependence on the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

Will it stay or will it go? Khan faces increased pressure from a unified opposition, as well as the military that it alleges is using him as a pawn. The opposition has asked for the prime minister’s resignation and has increasingly railed against the military’s involvement in politics. Whether the opposition succeeds in deposing the government will depend on a number of factors. The economy will play the biggest role in the government’s ability to survive. If the government can convince the public that it can manage the country through the economic crisis, it will likely survive.

The signs are worrying for the ruling party. The economy contracted in 2020 for the first time in decades, in large part due to the restrictions necessitated by the pandemic. Even before that, inflation was alarmingly high, with Pakistan suffering an economic downturn even before COVID-19 hit. If this increase in the cost of living continues, it could foment a downturn in public sentiment, and the opposition is banking on that for its movement to succeed. A lot depends on whether the security establishment keeps supporting the current government. The military is currently “on the same page” as the civilian government, but that can change, especially as public feeling changes. That, too, should depend largely on the economic performance of the government, as the military has taken a bigger role in economic matters than before and will be monitoring the situation closely.

An economy in trouble? It will be a tough road ahead for the economy in 2021, as the IMF austerity measures will need to be dealt with even as the government attempts economic recovery from the pandemic. The current account deficit shrunk by around 3 percent due to a fall in both exports and imports. Of more concern will be the 55-percent decrease in tax filers the past year, something the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government had vowed to take in the other direction. In fact, the tax-to-GDP ratio has fallen year on year under the current government. Economic growth in 2021 is expected to be around 1 percent and, thus, a tough year lies ahead. The PTI government has already changed the Federal Board of Revenue head four times in less than three years. This is part of a wider pattern. Cabinet reshuffles have become a regular occurrence, as have sackings and appointments in senior bureaucratic positions.

Such turnover does not lend confidence to the governing ability or viability of a government that is already a rookie when it comes to policymaking. Nor does history suggest reason for optimism. Pakistan has a history of mass uprisings during periods of economic crisis. Former Pakistani President Ayub Khan was ousted in 1969 after mass protests sparked by an increase in sugar prices. While the uprising against former Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf was catalyzed by the lawyers’ movement, it was during a period of economic recession, which exacerbated the overall resentment and helped lay the groundwork for dissent.

The military is currently ‘on the same page’ as the civilian government, but that can change, especially as public feeling changes.

CPEC and security: There is an increasing tilt in Pakistani foreign policy toward a development, rather than a purely security, approach. This is evidenced by the way the military has involved itself with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project. Former Inter Services Public Relations head Lieutenant General Asim Bajwa was appointed as the head of the project and, in November, parliament approved a bill that grants the military control of the project.

This has also led to a shift in which Pakistan’s economic relationship with China is getting stronger and its security impetus is also shifting toward the protection of the CPEC project from outside interference, with the likelihood that it was China that wanted greater involvement of the military in the project, due to security concerns. This shift in Pakistan’s policy is aptly illustrated in China’s bailing out Pakistan so it could pay its Saudi loan at the end of 2020.

The withdrawal of the United States from Afghanistan will have less of an impact than expected by some analysts, keeping in line with the overall trend in Pakistani policy. The Taliban have moved more toward Doha than Islamabad. While peace in Afghanistan will be a boon for Pakistan, its influence in effecting that has been minimized.

Sri Lanka

By Azeem Khan

In 2021, Sri Lanka looks likely to accelerate its slide into authoritarianism, as the Rajapaksa family consolidates and concentrates power, and the undemocratic consequences of the 20th Amendment to the constitution take root. Restrictions on religious freedom and general abuse of minorities’ rights look set to follow a similar pattern. The pandemic has increased the reliance on foreign borrowing, thus pushing Sri Lanka even more toward China, whose one-party system the Rajapaksas seem to aspire to as well.

Democracy in peril: After his party achieved a resounding two-thirds-majority victory in the parliamentary elections, Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa appointed his older brother Mahinda as the prime minister. This allowed the Rajapaksas to push through parliamentary reforms that do not bode well for democracy in 2021. Constitutional changes, such as the passage of the 20th Amendment, have effectively made the younger Rajapaksa a dictator, giving the president the ability to appoint his own superior judges and attorney general, sack ministers, dissolve parliament halfway through its term, and wield authority over independent commissions. Indeed, the militarization of Sri Lanka is in full swing as Gotabaya Rajapaksa has appointed ex-military officials as heads of many of the most important ministries. He has already utilized the dictatorial powers provided by the 20th Amendment and installed loyalists in important positions. In 2021, these changes are expected to take root and make the president even more powerful than he has been to date.

Human rights left behind: The Rajapaksa government has used the pandemic as an excuse to intensify its repressive and militaristic approach to governance. The Defense Ministry leads the island’s COVID-19 response and arrested sixty-six thousand in just the first two months of the pandemic. Even criticizing the government’s COVID-19 response was criminalized. Journalists and activists have been increasingly threatened, and the right to dissent has been increasingly taken away from Sri Lankans. The pandemic has also been used as an excuse for the suppression of religious freedom, demonstrated by the recent forced cremations of Muslims who died of COVID-19. A ban on cow slaughter further alienates religious minorities. The president has also pardoned war criminals, and his decision to withdraw from the United Nations resolution on investigations into war crimes during the civil war is a troubling signal of his government’s intentions. In 2021, the country’s sorry record of human-rights abuses is only likely to worsen as Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s constitutional changes take hold and empower him even more.

In 2021, the country’s sorry record of human-rights abuses is only likely to worsen as Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s constitutional changes take hold and empower him even more.

Debt burden and foreign policy: The pandemic has worsened Sri Lanka’s debt burden, as tourism dropped precipitously and will continue to be depressed in the new year. Along with the other economic ill-effects of COVID-19, Sri Lanka’s urgent need to address its debt burden will dictate the specifics of its foreign policy. The new government has been making efforts to cultivate positive regional relationships, particularly in its efforts to balance the India-China tension. It is expected that there will be a more deliberate turn toward China as the burden worsens, especially if India is not able to offer help in concrete terms, with projects aimed at economic development and the easing of the debt crisis.

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

The authors

Irfan Nooruddin is director of the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center and a professor in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

Harris Samad is the assistant director of the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Kaveri Sarkar is a project assistant at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Capucine Querenet is a research assistant at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Shashank Jejurikar was an intern at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Azeem Khan was an intern at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

All photos are courtesy of REUTERS.

More from the South Asia Center:

Image: Light illuminates a mountain range above the valley during sunset in Kathmandu, Nepal REUTERS/Navesh Chitrakar