IN BRIEF: Why the G7 summit matters, in seven charts

The last time the Group of Seven (G7) leaders met in person, Donald Trump was president of the United States and no one had heard of a disease called COVID-19. Now, as UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson plans to host his colleagues in Cornwall this weekend, the agenda is daunting. Can the world’s advanced economies learn from past mistakes and engineer a strong, inclusive global recovery?

Several significant storylines are converging to shape the challenging landscape in which these leaders will meet. Our GeoEconomics team tells those stories through the seven charts below.

Keep scrolling down to check out each of the charts and read our explanation of why it matters.

One of the most surprising aspects of the global economic recovery is that the United States is leading the charge. In fact, gross domestic product (GDP) growth this year in the United States could rival that of China. And it won’t stop there. The United States is the only advanced economy expected to come out of the COVID-19 crisis with higher growth in the medium term. Of course, five-year projections are always iffy. But you can be sure that US President Joe Biden will be focused on this chart during the G7 meeting—and that he’ll remind the other leaders that the United States unleashed unprecedented fiscal firepower to get to this enviable position.

This has been a record year for fiscal stimulus, with the United States alone spending over 25 percent of its GDP on such stimulus measures. These programs have been crucial in countering the economic shock of COVID-19. But as national debts grow worldwide, how much longer can governments sustain this level of fiscal support? What will the implications be of a shift away from such high amounts of expenditure? The G7 members should aim to coordinate their policies as they move toward post-recovery plans and use this summit as an opportunity to jointly pursue climate-change objectives and increase economic resilience.

To address the economic shock triggered by COVID-19, the G7 central banks have expanded their quantitative easing (QE) programs by a total of $10 trillion (or roughly half the size of the US economy) to support their countries’ recoveries and the functioning of global financial markets. The banks’ new asset purchases have increased the size of their cumulative balance sheets by roughly 65 percent since the beginning of 2020. With economic growth picking up across advanced economies and inflation rising in the US and Europe, the critical question is when the major central banks will begin to tap the brakes. To better understand the implications of future central-bank tapering for the global economy, explore the Atlantic Council’s Global QE Tracker.

Debt will be a key theme at the G7 summit, as countries work to strike a balance between economic relief and a healthy recovery. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, countries around the world pushed through massive fiscal-stimulus packages. As a result, all G7 countries saw a significant jump in their debt burdens. This spending is expected to continue through 2021.

The pandemic triggered job losses across the G7. But as economies open, unemployment rates in the G7 are declining from their 2020 pandemic-era highs. However, persistently low labor force participation rates (LFPR) in the G7, especially in Italy (with less than 50 percent of its adults participating in the labor force), continue to pose serious challenges for the long-run health of these economies and the sustainability of their entitlement programs. Aging populations are the main culprit here, forcing policymakers in the G7 to face difficult decisions about immigration and social-safety nets.

Trump’s corporate tax cuts have come under fire both domestically and internationally, but they actually brought the United States closer to the G7 average. While a new tax fight with Congress looms, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen achieved a major breakthrough on the international stage last week: getting her fellow G7 finance ministers to tentatively agree to a global minimum corporate tax. Reaching this agreement among the G7, however, was only the first step; the next challenge will be bringing on board countries like Ireland and Hungary that attract international businesses through their low corporate tax rates. Read Jeff Goldstein’s explainer on why 15 percent was the compromise number for the new global corporate rate, and how these moves might benefit the United States.

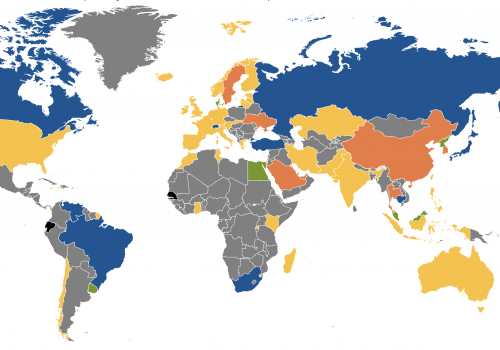

In early March, the global vaccine initiative COVAX announced its first round of COVID-19 vaccine allocations. The initial shipments were meant to consist of 238 million doses, which would be delivered to 109 recipient countries from February through the end of May. On average, each recipient nation was forecasted to receive enough doses to vaccinate just under 3 percent of its population. Supply-chain bottlenecks as well as vaccine nationalism have stymied this modest first allocation. As of June, COVAX has only been able to deliver 76 million of the 238 million doses initially allocated. However, as rich nations increasingly achieve acceptable vaccination thresholds and vaccine supplies become more available, expect deliveries to pick up. In June, President Biden announced that the United States will donate 75 percent of its unused vaccines to COVAX. He’ll surely highlight this commitment during his meetings at the G7 summit.