After months of delay, the US Congress in March passed renewed Compacts of Free Association (COFA) with Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republic of the Marshall Islands. These agreements extend a host of benefits and services to these Pacific Island states, as well as an obligation to defend them from attack, while allowing the United States extensive defense and security access.

The COFA are a necessary, but not sufficient, step to ensure US national security and the continued alignment of US interests and those of Pacific Island nations. While the compact states are only three in a region with diverse views and experiences, the holdup in passage of the COFA has intensified concern over the US commitment to the Pacific Islands.

China is hovering over the region and has already shown an ability to translate economic incentives into influence over policy in these countries. The congressional delay was just one more opportunity for Beijing to paint Washington as an inconsistent and unworthy partner for the Indo-Pacific region. As part of an ongoing bid to shape the region’s geopolitical position in its favor, China offered its own incentives to these Pacific Island nations. This included a promise to boost Palau’s tourism sector by filling every hotel and economic inducements to the Marshall Islands to shift policies in China’s favor. The implication of these efforts was that more benefits would quickly follow.

The delay in ratifying the COFA reinforced the perception that the United States is an unreliable partner.

China’s recent efforts to lure other Pacific Island governments into alignment with Beijing’s policy preferences heighten the importance of a consistent US focus on the region. Beijing’s interests include poaching Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, extending China’s reach through law enforcement agreements, and expanding the Chinese navy’s ability to operate farther from the mainland.

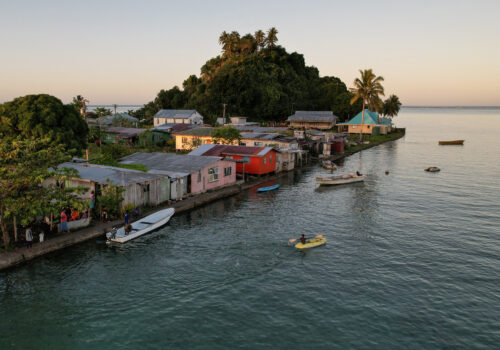

Beijing has made significant progress in achieving these goals in the past few years, with the Solomon Islands and Kiribati as two prime examples. Both countries switched diplomatic allegiance from Taiwan to mainland China in 2019, leading to a string of economic and security agreements. The Solomon Islands signed a security agreement with Beijing in 2022 and a policing agreement in 2023, igniting fears that China will seek access to port facilities for its naval vessels, causing diplomatic handwringing in Washington and Canberra. Meanwhile, in Kiribati, rumors persist that China might attempt to rebuild a military airstrip just 2,400 miles southwest of Hawaii. In fact, Chinese police officers were seen in Kiribati earlier this year, leading the United States to voice its concern in February.

These developments come as China has lavished persistent and generous attention on governments throughout the region, seeking influence through not only coercion but also economic inducements. Pacific Island countries seek economic development, and Chinese diplomats convey an interest in and understanding of local priorities (even as Beijing’s efforts are sometimes laced with corrupt or coercive intent). Beijing can also offer economic incentives that meet national or domestic political needs—in both the Solomon Islands and Kiribati, changes in policy have been accompanied by significant promises of aid and investment. China has made similar promises to other Pacific Island nations, including with some success in Fiji and Nauru. There have also been notable failures alongside these successes, but Beijing is not likely to be deterred.

To counter China’s influence, Washington must commit more resources and attention to the region. No doubt, the United States also has had policy successes, but US interests in the Pacific Islands are expansive, including protecting Taiwan’s international space, continued access to the territorial waters of partner countries, and a commitment to democratic governance. Yet these island nations do not necessarily share all the same concerns, especially when it comes to geopolitical competition. The United States—ideally in partnership with its allies and partners—must increase its understanding of local priorities and its set of economic incentives to more effectively convince these countries of the benefits of working with Washington and its partners.

To its credit, the Biden administration has made significant progress in expanding the US diplomatic and economic presence in the region, and many of the necessary tools are in place to meet the needs of Pacific Island partners. Cabinet-level visits and the Pacific Island leaders’ summit, hosted in Washington in September 2023, are significant, as is the administration’s 2022 Pacific Partnership Strategy. This high-level attention must be matched by a consistent presence throughout the region—importantly, Washington has established new embassies in the Solomon Islands and Tonga, and diplomatic outposts are forthcoming in Vanuatu and Kiribati. However, more engagement is needed, and these missions must be adequately resourced and staffed to yield a better appreciation of local needs, understand the domestic political dynamics that affect decision-making, and unearth attempts by China to gain influence.

Beyond diplomatic efforts, the United States should bolster its relationship with the Pacific Islands through economic and security-related cooperation. The Pacific Partnership Strategy engages with some of these issues, but more—and more concrete—measures are needed. Most importantly, climate change and rising sea levels are an existential security threat for the region that demands greater action. Beyond US domestic efforts to combat the climate crisis, Washington has promised investment in climate forecasting and research, help promoting economic resiliency and climate adaptation, and support for Pacific Island Forum initiatives.

On economic issues, the United States should help boost these countries’ economies while simultaneously increasing resiliency to China’s opaque overtures. It can do this by facilitating private-sector involvement to spur growth, developing partnerships with local actors and nongovernmental organizations, and helping to increase governance capacity. Washington could, for example, expand access to risk assessment and technical resources, contract renegotiation, and debt restructuring resources to ensure these countries have access to technical resources to make informed decisions about economic engagement with China. Pursuing opportunities for cooperation with Quadrilateral Security Dialogue partners could serve as an additional avenue for collaborative efforts to enhance stability and prosperity in the Pacific Islands. These opportunities might include partnering with Australia and Japan to provide financing and initiating joint efforts to limit the harmful legacy of nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands.

The delay in ratifying the COFA reinforced the perception that the United States is an unreliable partner. “Our nation has been a steadfast ally of the United States,” said President Hilda Heine of the Marshall Islands before passage of the COFA had been secured, “but that should not be taken for granted.” This concern extends well beyond the three COFA countries in the region. In this light, China—with its ready promises of economic incentives and persistent outreach—can appear an appealing alternative. Warnings of the risks and challenges of accepting Beijing’s largesse run up against the need for economic growth and attention to local needs.

The United States, Australia, and their partners can offer their own set of economic inducements, grounded in the rules-based international order and in support of sovereign decision-making. Such a future benefits the United States and Pacific Island nations—but it requires consistent and timely action.

William Piekos is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub.

Further reading

Fri, Mar 29, 2024

Bolstering cooperation among Quad and Pacific Island countries

Issue Brief By Parker Novak, Kyoko Imai

As the Pacific Islands’ relevance grows, there’s an influx of diplomatic attention and development assistance as external powers seek to curry favor with the sixteen countries. Australia, India, Japan, and the United States (the Quad) seeks to bolster regional engagement to address key regional issues including climate, connectivity, economic development, and maritime security.

Tue, Aug 15, 2023

Showing up is half the battle, and the United States is doing so in the Pacific Islands

New Atlanticist By Parker Novak

USAID Administrator Power’s visit to Papua New Guinea and Fiji highlights the importance of high-level diplomacy and soft power in the strategically located region.

Tue, Jul 25, 2023

As Blinken visits Tonga, the US needs to think beyond China in the Pacific Islands

New Atlanticist By Parker Novak

Geopolitics is important, but Washington’s relations with the strategically located region need to be about more than competition with Beijing.

Image: China's President Xi Jinping arrives at APEC Haus, during the APEC Summit in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea November 18, 2018. REUTERS/David Gray