Investigating China’s economic coercion: The reach and role of Chinese corporate entities

Table of contents

Introduction

Corporate entities in Chinese economic statecraft

Methodology

Exploring Chinese corporate entities and links to influence

Policy recommendations

Introduction

China’s economic statecraft has expanded in line with Beijing’s vision for an international environment that is more conducive to its interests. Chinese President Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are willing to use every means at their disposal to achieve this goal, bringing the full force of the party-state to bear in support of Xi’s objectives abroad and against perceived enemies of the Chinese government. Economic statecraft—the use of economic means to pursue foreign policy goals—has been a consistent feature of Xi’s dealings with CCP competitors and adversaries. Intensifying US-China strategic competition and Beijing’s increasingly overt attempts to assert its preferences only further emphasize the importance of confronting China’s use of economic coercion and influence and understanding the reach of Chinese companies.

The deliberate use of economic ties to achieve geopolitical objectives is underpinned by corporate entities that facilitate trade, investment, and financial flows.1For more on the coercive potential of global economic interdependence, see Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman, “Weaponized Interdependence: How global economic networks shape coercion,” International Security 44 (1) (2019): 42–79. Beijing’s preference for plausible deniability and nontransparency in theory makes corporate entities an attractive mechanism through which to signal its displeasure and to achieve strategic goals. Understanding the reach and role of such entities is, therefore, key to identifying where Beijing might be best positioned to advance its economic statecraft. To that end, this report explores avenues through which researchers can investigate these issues, considers industries that could be vulnerable to future coercion and influence, and offers policy recommendations to counter China’s economic statecraft.2In this report, influence or economic influence refers to the ability of a state to alter the policy behavior of a target state or entity through the manipulation of economic measures; this is not to be conflated with influence operations through social media, disinformation, or related propaganda or discourse manipulation efforts. For an example of the latter, see Kenton Thibaut, China’s discourse power operations in the Global South, Atlantic Council, April 20, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/chinas-discourse-power-operations-in-the-global-south/.

Corporate entities in Chinese economic statecraft

Despite its recent economic difficulties, China’s size ensures that it will remain a center of economic activity for the foreseeable future. Corporate entities based in China play an essential role in expanding the country’s economic engagement.3All Chinese companies must report basic information to the State Administration of Market Regulation’s National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System. “Understanding Chinese Corporate Structures,” Sayari Learn, accessed September 23, 2023, https://learn.sayari.com/understanding-chinese-corporate-structures/. As Chinese firms seek to—and are encouraged by the government to—expand into foreign markets, the unique structure of China’s party-state apparatus offers Beijing the levers to wield significant influence over Chinese corporate entities and, through the potential manipulation of these entities, the policies of the target country.

The connection between Chinese companies and the CCP is fundamentally different from that of Western companies and their governments. There are numerous high-profile examples of Beijing directing corporate entities to meet the strategic demands of the party-state—such as ZTE selling technology to sanctioned countries or China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) moving an oil rig into Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone.4Scott L. Kastner and Margaret M. Pearson, “Exploring the Parameters of China’s Economic Influence,” Studies in Comparative International Development 56 (2021): 31, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-021-09318-9; Michael Green et al., Countering Coercion in Maritime Asia: The Theory and Practice of Gray Zone Deterrence (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic & International Studies, May 2017), 202–223. ZTE is a mixed-ownership Chinese technology firm. CNOOC is one of China’s largest state-owned oil companies. Experts have coined the term “CCP Inc.” to describe this Chinese state-capitalist ecosystem of financing and corporate entities, building off the previously used “China Inc.” label.5Jude Blanchette, From “China Inc.” to “CCP Inc.”: A new paradigm for Chinese state capitalism, Hinrich Foundation, February 2021, https://www.hinrichfoundation.com/media/swapcczi/from-china-inc-to-ccp-inc-hinrich-foundation-february-2021.pdf. They highlight the CCP’s influence over state-owned enterprises (SOEs), but also its increasing penetration of private firms through mixed-ownership structures.6Barry Naughton and Briana Boland, CCP Inc.: The Reshaping of China’s State Capitalist System, Center for Strategic & International Studies, January 2023: 18–20, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-01/230131_Naughton_Reshaping_CCPInc_0.pdf?VersionId=pJl3iB.DqMILjtq_qMx.8eN5IvUOHg.Y.

China’s state-capitalist system gives the CCP the opportunity to orchestrate the economic activity of state-run financial institutions, SOEs, and even private corporate entities through a number of control mechanisms.7Naughton and Boland, CCP Inc.; James Reilly, Orchestration: China’s Economic Statecraft Across Asia and Europe (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2021); Kastner and Pearson, “Exploring the Parameters,” 33; Wendy Leutert, “Firm Control: Governing the State-Owned Economy Under Xi Jinping,” China Perspectives (2018), http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/7605. The State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) administers state firms owned by China’s central government, which are concentrated in strategically important sectors; provincial corporations are guided by similar entities.8Wendy Leutert notes four existing governance mechanisms that the Xi administration has used to reclaim authority over SOEs: central leading small groups, the cadre management system, party committees, and campaigns. Leutert, “Firm Control,” 27. CCP governance mechanisms include requirements to create party cells to monitor and provide guidance for following CCP goals, and party committees are involved in all major strategic decisions, appointments, and projects.9Naughton and Boland, CCP Inc., 10. The government has instituted several national security laws, including the 2017 National Intelligence Law, that compel firms to provide information or support to the Chinese state if asked.

However, even as the party-state solidifies control mechanisms over corporate entities, the CCP’s command over China-based firms is not ironclad. US policy makers should not assume that the CCP is intent on or effective in its use of economic statecraft, nor that Chinese corporate entities are willing participants.10William J. Norris, Chinese Economic Statecraft: Commercial Actors, Grand Strategy, and State Control (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016). Chinese corporate entities pursue commercial ties abroad for many reasons, and many are made without the CCP’s foreign policy goals in mind—and even the party-state can have multiple or conflicting aspirations for this economic engagement.11Beijing can encourage non-conditional economic activity abroad for several possibly overlapping reasons, including future strategic gain, national economic strength, and support for Chinese companies abroad. Kastner and Pearson, “Exploring the Parameters,” 20–24. See also Albert O. Hirschman, National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade (University of California Press, 1945); Michael Mastanduno, “Economic Statecraft, Interdependence, and National Security: Agendas for Research” in Power and the Purse: Economic Statecraft, Interdependence, and National Security, eds. Jean-Marc F. Blanchard, Edward D. Mansfield, and Norrin M. Ripsman (London: Frank Cass, 2000). Scholarship on the topic highlights significant principal-agent problems in the Chinese state’s relationship with firms and their differing interests and goals.12Kastner and Pearson, “Exploring the Parameters,” 31–36; Norris, Chinese Economic Statecraft; Erica Downs, China’s National Oil Companies Return to the World Stage: Navigating Anticorruption, Low Oil Prices, and the Belt and Road Initiative, NBR Special Report no. 68, 2017; Xiaojun Li and Ka Zeng, “To Join or Not to Join? State Ownership, Commercial Interests, and China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Pacific Affairs 92 (1) (2019), https://doi.org/10.5509/20199215. Research on the State Grid Corporation of China, for example, shows how this SOE has been able to push party-state policy in its favor.13Yi-chong Xu, “The Search for High Power in China: State Grid Corporation of China” in Policy, Regulation, and Innovation in China’s Electricity and Telecom Industries, Lorent Brandt and Thomas G. Rawski (Cambridge University Press, June 2019). Even projects that are ostensibly driven by the Chinese state can simply be preexisting commercial pursuits that are rebranded in line with state goals (such as Xi’s ubiquitous Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI)—suggesting that Chinese companies, not the CCP, are the primary force behind these investments and projects.14Kastner and Pearson, “Exploring the Parameters,” 35.

Those caveats aside, Beijing has several mechanisms through which to use the reach of China-based corporate entities to influence the policy behavior of other actors. The most direct of these are economic ties as a source of bargaining power, and growing dependence on China can potentially increase vulnerability to Chinese economic coercion.15Kastner and Pearson, “Exploring the Parameters,” 24–31. The authors also identify economic ties as a means of creating vested interests, transformation of public and elite opinion about China, and structural power. The market share of Chinese companies can allow Beijing—through the reach of these entities—to threaten, impose costs on, or otherwise influence policy in a target country through national-level policies, such as informal trade restrictions, administrative measures, or other means. A large share of a market can also enable China to alter trade flows and supply chains to its benefit or in ways that disadvantage other countries or companies—one of the fundamental challenges of contending with a state-capitalist system like CCP Inc.16Francesca Ghiretti and Jacob Gunter, “COSCO’s Hamburg Terminal Acquisition: Lessons for Europe,” War on the Rocks, November 28, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/11/coscos-hamburg-terminal-acquisition-and-the-lessons-europeans-should-take-away/.

Recent studies of Chinese economic coercion indicate that China’s overt attempts have increased in the past few years and provide important insights into the current state of China’s economic statecraft.17Aya Adachi, Alexander Brown, and Max J. Zenglein, Fasten your seatbelts: How to manage China’s economic coercion, MERICS China Monitor, August 25, 2022, https://merics.org/en/report/fasten-your-seatbelts-how-manage-chinas-economic-coercion; Fergus Hanson, Emilia Curry, and Tracy Beattie, The Chinese Communist Party’s coercive diplomacy, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Policy Brief, Report No. 36, 2020, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/chinese-communist-partys-coercive-diplomacy; Fergus Hunter et al., Countering China’s coercive diplomacy, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Policy Brief, Report No. 68, 2023, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/countering-chinas-coercive-diplomacy; Peter Harrell, Elizabeth Rosenberg, and Edoardo Saravalle, China’s Use of Coercive Economic Measures, Center for a New American Security, June 2018, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/chinas-use-of-coercive-economic-measures. First, Beijing’s coercive economic actions fall into a few broad categories—among them, popular boycotts, administrative discrimination, empty threats, legal defensive trade measures, informal trade restrictions, investment restrictions, and limitations on tourism. Second, the targets of public coercion are somewhat predictable. Economically, they are most often small, democratic countries. Within these countries, Beijing’s coercive measures are aimed at strategic industries with a strong political lobby in the targeted country. At the same time, China often avoids targeting industries that are integral to strategically important sectors of the Chinese economy.18Significantly, China’s unwillingness to target sectors that are strategically important to it has meant that high-tech products have been largely missing from past publicized coercive attempts. Adachi, Brown, and Zenglein, Fasten your seatbelts, 8. Specific to China’s relationship with Taiwan, see Bonnie S. Glaser and Jeremy Mark, “Taiwan and China Are Locked in Economic Co-Dependence,” Foreign Policy, April 14, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/04/14/taiwan-china-econonomic-codependence/. Third, the proximate triggers of Beijing’s exertion of economic coercion are most often related to national sovereignty, national security issues, political legitimacy, and territorial disputes; however, these perceived provocations are evolving to include issues such as China’s international image, treatment of Chinese companies overseas, and countries’ imposition of broader perceived anti-China policies.19Matthew Reynolds and Matthew P. Goodman, Deny, Deflect, Deter: Countering China’s Economic Coercion, Center for Strategic & International Studies, March 2023, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-03/230321_Goodman_CounteringChina%27s_EconomicCoercion.pdf?VersionId=UnF29IRogQV4vH6dy6ixTpfTnWvftd6v; Adachi, Brown, and Zenglein, Fasten your seatbelts.

This report was created alongside a series of videos on the actions of Chinese corporate entities abroad. Watch the full series here:

Methodology

This report uses publicly available information to investigate the reach of Chinese corporate entities abroad and to uncover their role in Beijing’s economic coercion and influence attempts. It seeks to advance future research in this area by identifying important means and techniques through which to assess the reach and role of Chinese corporate entities. A further focus is the impact of China’s economic statecraft on US interests and the ways in which the United States and its partners can counter these efforts.

The report endeavors to distinguish between economic coercion and influence, which are not synonymous. Economic coercion involves one actor’s use of threats or actions against economic engagement (i.e., trade, investment, or financing) to force another actor to do something it would not otherwise do. By contrast, economic influence encompasses a much larger range of actions and does not necessarily involve a threat or coercive attempt, making the link between action and outcome all the more important.20Most notably, economic inducements—i.e., positive incentives—can be used to gain influence over a target country.

Evaluating Sources of Information on Chinese Corporate Entities

The first challenge of this research involved sifting through large amounts of data to identify Chinese corporate entities, their networks of ownership and acquisitions, and their upstream beneficiaries. This project has drawn on a wide range of resources to uncover the economic relationships between actors. The depth and breadth of information varies widely across jurisdictions, languages, and industries, making a factual investigation a time-consuming and complex process.

- Company websites and social media: There is a significant amount of information on Chinese corporate websites, in English, Chinese, and local languages. In conducting business abroad with many different actors, these entities have incentives to produce flashy websites and publicize their deals, just like other corporations. Some SOEs emphasize their deep ties in the Chinese market and even go so far as to brag about connections to the government and the ability to conduct business easily. While this public information should be consumed with caution and skepticism, it gives insight into the reach of these companies and reveals the extent of relationships.

- Corporate records: While the quality of such records varies widely between countries, they allow researchers to find connections that were not necessarily obvious before. Large databases—such as Sayari Graph, which was deployed in support of this project—can help aggregate vast volumes of data, and they can be used to reveal direct ownership links between entities and deployed alongside trade, shipping, and geospatial data to offer further insights into connections between and across jurisdictions. While subject to some of the same data and translation challenges as other research methods, they offer another significant avenue through which to investigate the reach of Chinese entities.

- Local knowledge: Conversations with locally based experts proved key to uncovering less-advertised Chinese economic activity and opening investigations into the entrenched role of China-based corporate entities in various industries and countries.

- National agencies: This data is not always reliable—particularly when dealing with numbers from Chinese agencies—but it still offers a starting point into connections and can highlight patterns of trade and investment. The Chinese Ministry of Commerce, for example, has a list of entities with overseas investments. In other countries, trade or investment data, while variable in quality and accessibility, can help reveal vulnerabilities and dependencies.

- Contracts and memoranda of understanding (MOUs): When publicly available, contracts and MOUs can reveal previously unknown relationships, including legal connections, between companies, states, and individuals. These documents are not always in the public domain and can be difficult to obtain.

Chinese Corporate Entities as Vehicles for Coercion and Influence

Connecting Chinese corporate entities to the exertion of coercion or influence was a second and potentially greater challenge of this research. Attempts at coercion or influence are not clear-cut, and Beijing—like other actors—has incentives to hide its efforts. Without a smoking gun, it is easy to jump to the conclusion that China-based actors are working at the party-state’s behest, but policy makers should be skeptical of the ability or willingness of Chinese corporate entities to hurt their own business prospects.

Importantly, obvious coercive attempts represent, to some degree, a failure.21For more on selection bias in the study of economic coercion, see Daniel W. Drezner, “The Hidden Hand of Economic Coercion,” International Organization 57 (3) (2003): 643–59, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818303573052. The most oft-cited cases of Chinese economic coercion are in countries that are largely democratic and are already aligned with the United States and the West—e.g., Lithuania, South Korea, Japan, and Australia. These countries often have options to blunt Chinese economic coercion and alternative partners willing to assist them in avoiding the repercussions associated with resisting Beijing’s policy demands. But even publicized failure—when coercion or influence does not cause the target state to alter its policies in line with the coercing actor’s preferences—can succeed in other ways. For example, it can help protect China’s domestic economy, impose significant costs to punish the target, or serve as a deterrent signal to third-party actors from taking certain actions by increasing the perceived costs of that behavior.

In past cases of Chinese economic coercion, Beijing most often leveraged the reach of Chinese corporate entities through restrictions imposed by national-level agencies. These coercive measures abuse established links between these Chinese companies and the target country. For example, China’s customs authorities have raised non-tariff barriers to trade; the Chinese Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the China National Tourism Administration, or Chinese embassies have imposed tourism restrictions; and China’s Ministry of Commerce has instigated anti-dumping investigations against target industries.22Reynolds and Goodman, Deny, Deflect, Deter. Non-tariff barriers to trade include the imposition of blanket sanitary and phytosanitary measures, as was the case with bananas from the Philippines and Australian dairy imports in 2016; increased scrutiny of imported goods and their paperwork or, in the extreme, the removal of Lithuania from the customs clearance system; and fees levied on cross-border shipments, as was the case against Mongolian copper. The Ministry of Commerce used anti-dumping measures against Australian wine and anti-subsidy tariffs against barley. In select cases, Beijing has sent orders to China-based corporate entities to restrict economic exchange with targeted countries, highlighting an even more direct and focused attempt at coercion.23To be labeled as an episode of economic coercion via a corporate entity, the attempt must be both threatening economic ties and channeled through a Chinese company (i.e., not apply to an entire industry or sector). Cases were drawn from two Australian Strategic Policy Institute reports on China’s coercive diplomacy. Hanson, Curry, and Beattie, The Chinese Communist Party’s; Hunter et al., Countering China’s. These measures often supplement other, more formal restrictions. Tourism restrictions can be funneled through specific travel agencies to halt or restrict bookings in a particular country.24Hanson, Curry, and Beattie, The Chinese Communist Party’s. Countries that were targeted in this way include the Philippines in 2012, Japan in 2012, Taiwan in 2016, Palau in 2017, and South Korea in 2017. Against Australia, Chinese agencies directed companies to restrict the import of specific goods, including coal, cotton, and liquified natural gas.25In some industries, these measures grew into complete informal bans. Australia was subject to coercive economic measures for calling for an investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, as well as earlier policy decisions related to regional security, 5G telecommunications, and foreign interference. Hunter et al., Countering China’s. Beijing’s coercive actions against Lithuania in late 2021 included reports that a state-owned Chinese railway operator informed Lithuanian customers that the direct freight link between the two countries would be put on hold.26Finbarr Bermingham, “China halts rail freight to Lithuania as feud deepens over Taiwan,” South China Morning Post, August 18, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3145520/china-halts-rail-freight-lithuania-feud-deepens-over-taiwan; Tao Mingyang, “Lithuanian exports of farm products to China face challenges as tension grows,” Global Times, August 24, 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202108/1232344.shtml. Lithuania was targeted by Chinese economic coercion in retaliation for naming its de facto embassy for Taiwan instead of Taipei in November 2021, which Beijing saw as a violation of the One-China principle. The Chinese company denied that it had canceled the freight link, but state media such as the Global Times and the People’s Daily amplified the threat and questioned the future of the rail link.

Looking outside well-publicized cases, countries in the Global South have fewer alternatives to Chinese engagement and generally garner less attention and investment from the West, which makes China’s domineering economic position harder to resist—Beijing’s success in drawing Taiwan’s few remaining diplomatic partners through inducements provides one such example.27Thomas Shattuck, “The Race to Zero?: China’s Poaching of Taiwan’s Diplomatic Allies,” Orbis 64 (2) (2020): 334–352, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2020.02.003. Most recently, Honduras switched diplomatic recognition to China in early 2023; since Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen took office in 2016, eight additional countries have made the switch: Nicaragua, Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Panama, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Burkina Faso, and Sao Tome and Principe. Such cases are more likely to fall under the category of influence than coercion, because there is less need for an overt threat—whether in public or private—to limit economic interaction. Either way, the target is incentivized to hide that it has been influenced successfully. Moreover, asymmetry in market size introduces the challenge of anticipated reactions, in which one actor (smaller state) might conform its behavior to what it believes are the desires of another (China).28Scott L. Kastner, “Analysing Chinese Influence: Challenges and Opportunities” in Rising China’s Influence in Developing Asia, ed.Evelyn Goh (Oxford University Press, 2016): 275. This type of influence is even more difficult to identify, as a clear policy request has not necessarily been made.

Assessing Vulnerability

Building off of previous studies, this report emphasizes five factors in assessing vulnerability to Chinese economic coercion and influence in a prospective target country:

29Adachi, Brown, and Zenglein, Fasten your seatbelts, 8; Reynolds and Goodman, Deny, Deflect, Deter, 16–20. In the Australian Strategic Policy Institute report, vulnerable sectors are defined as those where risks and potential costs appear elevated, based on observed characteristics of products targeted in the past. Hunter et al., Countering China’s, 34–35. The views of government leaders and politicians toward China are particularly salient when considering domestic political attitudes in the prospective target country.

The first four factors are heavily determined by the presence of Chinese corporate entities, which collectively ensure the importance of China as a trading partner, source of investment, and/or market for multinational corporations.

Of these, dependence demands additional attention—it is key in determining vulnerability to China’s economic coercion and influence, but dependence and vulnerability are often considered equivalent.30As a RAND report argues, “having high levels of inputs for potential influence… does not necessarily provide the influencer state with unquestioned control over targeted countries. The route from potential to actual influence is complex, rocky, strewn with land mines, and anything but straight and linear.” Michael J. Mazarr et al., Understanding Influence in the Strategic Competition with China, RAND Corporation, 2021: 17, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA200/RRA290-1/RAND_RRA290-1.pdf. However, asymmetric dependence in China’s favor does not necessarily mean that Beijing can successfully deploy economic statecraft measures.31Francesca Ghiretti and Hanns W. Maull, “Diversification Isn’t Enough to Cure Europe’s Economic Dependence on China,” Diplomat, January 27, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/01/diversification-isnt-enough-to-cure-europes-economic-dependence-on-china/. Likewise, negligible levels of dependence do not always shield a potential target from Chinese economic coercion. In short, dependence is important but is one of several factors that must be accounted for in assessing vulnerability to Chinese economic coercion and influence. In particular, when looking at China’s past coercive economic attempts—which are predominantly against democratic and more developed countries with diverse sets of trading partners—many of Beijing’s measures are aimed not at industries that are dependent on China, but at politically influential or symbolic industries in the target country, and they do not necessarily impose significant economy-wide costs on the target.32Reynolds and Goodman, Deny, Deflect, Deter, 7–19; Harrell, Rosenberg, and Saravalle, China’s Use of Coercive, 20–21.

Not all countries, however, have a sufficiently diverse set of industries or alternatives to resist China’s measures. What if the politically influential or symbolic industry targeted by Chinese measures (or in which Chinese companies have a large market share) makes up a large share of a country’s exports, gross domestic product, inbound investment, or another economic indicator? Such a scenario is more likely in the Global South, where China—through the reach of Chinese corporate entities—can use its centrality to influence policy behavior in the target country without the use of explicit threats or coercion. Couple this with a perceived lack of alternatives in these countries, and China’s strong position in just one industry could make resisting Beijing’s policy preferences costly to a country’s overall economic health and development.

Exploring Chinese corporate entities and links to influence

This report presents three case studies illustrating possible channels of coercion and influence and explores variability in their prospective effectiveness. The first two cases—related to the tuna fishing industry in Kiribati and state-owned China Oil and Foodstuffs Corporation’s (COFCO’s; 中国粮油食品集团有限公司) ownership of a grain logistics network in Romania—highlight the difficulties in investigating the reach of Chinese corporate entities and the various factors linking these entities to coercive potential or influence. In Kiribati, all factors made the country vulnerable to Beijing’s economic statecraft, but in Romania, they pull in different directions, and COFCO’s commercial dealings have yet to yield evidence of attempted political influence.

The third case study, on container transport and logistics networks in Southeastern Europe, is borne of an investigation into China’s previous coercive attempts, which skew heavily toward threats or actions against established trade relations. The operations of China COSCO Shipping Corporation Limited (COSCO; 中国远洋海运集团有限公司)—a leading Chinese SOE for ocean shipping and port operations—and its subsidiaries offer China both a dominant market share in the region and the ability to affect the flow of goods as leverage. Through these connections, COSCO and the Chinese party-state have the potential to coerce or influence policy behaviors in the region, though the costs of jeopardizing COSCO’s model BRI efforts in Greece and the region are potentially prohibitive.

Case Study 1: Tuna Fishing in Kiribati

The challenges of investigating the impact of Chinese corporate entities are made apparent in Kiribati, where President Taneti Maamau has overseen a pro-China shift since his election in 2016 and reelection in 2020. Lured by promises of aid and commercial opportunity, Maamau switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China in 2019.33The aid request from Kiribati to China included loans and a Boeing 737 aircraft, according to a Taiwanese official. ABC Australia, “China gains the Solomon Islands and Kiribati as allies, ‘compressing’ Taiwan’s global recognition,” September 21, 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-21/china-new-pacific-allies-solomon-islands-kiribati-taiwan/11536122; Yimou Lee, “Taiwan says China lures Kiribati with airplanes after losing another ally,” Reuters, September 20, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-taiwan-diplomacy-kiribati-idUSKBN1W50DI; Christopher Pala, “China Could Be in Reach of Hawaii After Kiribati Elects Pro-Beijing President,” Foreign Policy, June 19, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/19/kiribati-election-china-taiwan/. The government of Kiribati opened the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA)—previously a United Nations World Heritage Site—to commercial fishing to boost revenue from fishing permits, with Chinese encouragement; signed onto multiple agreements with China, including the BRI; and left the Pacific Islands Forum in 2022, reportedly with Beijing’s support.34Kiribati rejoined the forum less than a year later. Jill Goldenziel, “Kiribati’s Liaison With China Threatens Sushi and U.S. Security,” Forbes, July 22, 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jillgoldenziel/2022/07/22/kiribatis-liaison-with-china-threatens-sushi-and-security/; Kate Lyons, “Kiribati to return to Pacific Islands Forum at vital moment for regional diplomacy,” Guardian, January 30, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/30/kiribati-to-return-to-pacific-islands-forum-at-vital-moment-for-regional-diplomacy. Rumors persist around possible Chinese military use of an old runway on the island of Kanton, just 3,000 kilometers southwest of Hawaii; the Kiribati government has asserted that the upgraded airstrip is a nonmilitary project to improve tourism and transport links.35If it came to pass, the airstrip would represent by far the closest Chinese facility to Hawaii and US Pacific Command. Jonathan Barrett, “Kiribati says China-backed Pacific airstrip project for civilian use,” Reuters, May 13, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/kiribati-says-china-backed-pacific-airstrip-project-civilian-use-2021-05-13/. For examples of Western skepticism of Chinese intentions in Kiribati and the Pacific Islands more broadly, see Steve Raaymakers, “China expands its island-building strategy into the Pacific,” Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, September 11, 2020, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/china-expands-its-island-building-strategy-into-the-pacific/; Col. Bud Fujii-Takamoto, “Strategic Competition in the Pacific: A Case for Kiribati,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, December 7, 2022.

The Kiribati government’s decision to switch diplomatic recognition—and the subsequent opening of PIPA—is reportedly related to China’s influence over the fishing industry.36Barbara Dreaver, “Exclusive details on Kiribati govt’s plan to ditch marine reserve,” 1News, November 15, 2021, https://www.1news.co.nz/2021/11/14/exclusive-details-on-kiribati-govts-plan-to-ditch-marine-reserve/; Lawrence Chung, “Taipei down to 15 allies as Kiribati announces switch of diplomatic ties to Beijing,” South China Morning Post, September 20, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3029626/taiwan-down-15-allies-kiribati-announces-switch-diplomatic; Mark Godfrey, “Zhejiang Ocean Family lauds Kiribati tuna haul,” SeafoodSource, March 17, 2021, https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/zhejiang-ocean-family-lauds-kiribati-tuna-haul. Tuna fishing licenses and access fee revenues for the island nation’s 3.5 million square kilometer exclusive economic zone made up 70 percent of the island nation’s fiscal revenues in 2020 and hovered between 60 percent and 90 percent from 2014 to 2018.37Mark Godfrey, “Study of Kiribati economy finds it is over-reliant on tuna fishery,” SeafoodSource, August 18, 2022, https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/environment-sustainability/study-of-kiribati-economy-finds-it-is-over-reliant-on-tuna-fishery; Natalie Firth, Sally Yozell, and Tracy Rouleau, CORVI Risk Assessment: Tarawa, Kiribati, Stimson Center, August 4, 2022, https://www.stimson.org/2022/corvi-risk-profile-tarawa-kiribati/; International Monetary Fund, Kiribati: Selected Issues, IMF Country Report No. 23/226, June 23, 2023: 42. Fish, primarily skipjack tuna, are one of the country’s main exports, along with crude coconut oil and unprocessed copra (coconut), though Kiribati’s key export markets include Australia, Japan, the United States, and Australia—not China.38Firth, Yozell, and Rouleau, CORVI Risk Assessment.

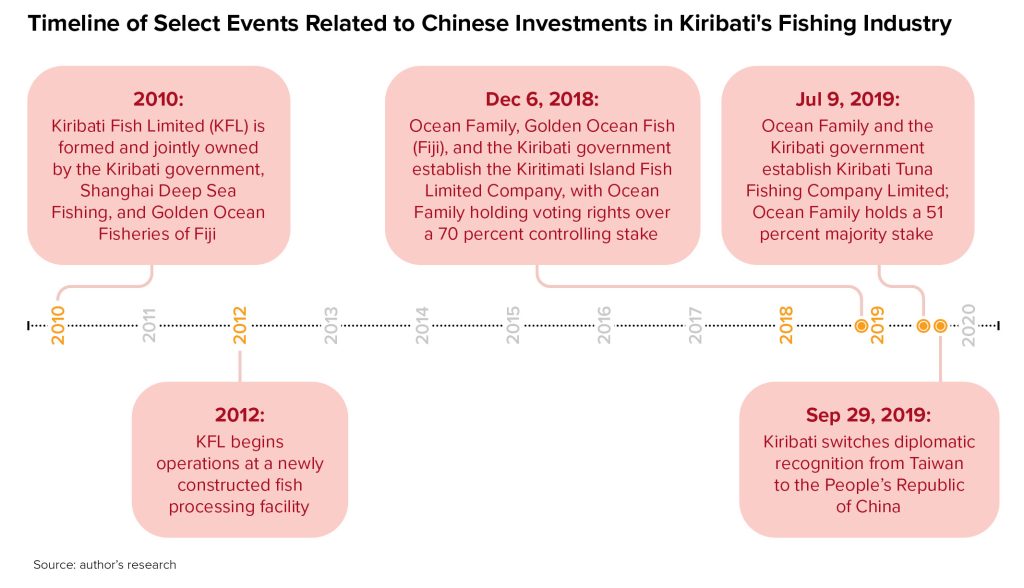

Chinese investment in the Kiribati fishing industry is longstanding but accelerated in the year prior to the diplomatic switch. The Kiribati Fish Limited (KFL), formed in 2010, is jointly owned by the Kiribati government (40 percent), Shanghai-government-owned Shanghai Deep Sea Fishing (上海远洋渔业有限公司; 20 percent), and Golden Ocean Fisheries of Fiji (40 percent)—in which Shanghai Fisheries (上海水产), the parent company of Shanghai Deep Sea Fishing, has a 20 percent stake.39“Kiribati Fish Ltd.,” accessed June 21, 2023, https://kiribatifishltd.com/. KFL began operations at a newly constructed fish processing facility in 2012 with a reported investment of $11 million, and Chinese-language media reports highlight Shanghai Fisheries’ role in supporting KFL’s profitability and ongoing tuna fishing initiatives, such as a tuna transshipment hub.40“不忘初心,砥砺前行“上海水产”在基里巴斯的守护与发展纪实” [Stay True to the Original Intent, and Continue to March Forward with Purpose: A Chronicle of Shanghai Fish’s Development and Wardship in Kiribati.], Shanghai Technology and Finance, September 26, 2019, https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/84312376. According to the “Kiribati 20-Year Vision 2016-2036,” Kiribati Fish Limited is the only company engaged in processing and exporting fresh and frozen fish. Ministry of Finance & Economic Development, “Kiribati 20-Year Vision 2016-2036,” Government of Kiribati, July 5, 2018, https://www.mfed.gov.ki/publications/kiribati-20-year-vision-2016-2036.

More immediate to the Maamau administration’s decision to switch diplomatic recognition, a private Chinese company, Zhejiang Ocean Family Company (浙江大洋世家股份有限公司), invested 4.5 million Australian dollars (approximately $3 million) in two companies, Kiritimati Island Fish Limited (圣诞岛渔业有限公司) and Kiribati Tuna Fishing Company Limited (基里巴斯金枪鱼捕捞有限公司). Ocean Family holds a 40 percent stake in Kiritimati Island Fish Limited but has a joint voting agreement with Golden Ocean (30 percent) that affords the Chinese company a 70 percent controlling stake. The Kiribati government owns the remaining 30 percent. Kiribati Tuna Fishing is a straightforward joint venture between Ocean Family and the government, with Ocean Family holding a 51 percent share.41“浙江大洋世家股份有限公司首次公开发行股票招股说明书” [Zhejiang Ocean Family Co. Ltd Initial Public Offering Disclosure Form], , accessed April 4, 2023, 77–79, https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H2_AN202106281500540089_1.pdf.

Though Ocean Family is privately owned, its parent company has long-standing ties to the CCP. Ocean Family is part of the Wanxiang Group (万向集团), a Chinese conglomerate that primarily manufactures automotive components. Wanxiang Group is led by Lu Weiding, a CCP representative of the National People’s Congress and the company’s secretary of the party committee.42“万向集团公司召开全国两会精神传达会暨 习近平总书记系列重要讲话精神学习会” [Wanxiang Group Holds Study Group and Meetings on Spirit of the Two Meetings and Spirit of General Secretary Xi’s Series of Important Talks], March 28, 2023, http://www.wanxiang.com.cn/index.php/news/info/2458; “《人民日报》:鲁伟鼎代表——为中国式现代化贡献民企力量” [People‘s Daily: Representative Lu Wei Ding Express Civil Enterprises Are Contributing to the Chinese Style Modernization], March 8, 2023, http://www.wanxiang.com.cn/index.php/news/info/2454. Ocean Family also benefitted from a 2016 deal negotiated by the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture with Kiribati, which increased fishery access for Chinese fishing companies.43Mark Godfrey, “Chinese official inks tuna deal in Kiribati,” SeafoodSource, July 20, 2016, https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/chinese-official-inks-tuna-deal-in-kiribati.

The significance of KFL and the Ocean Family investments in Kiribati’s tuna fishing industry was first revealed through contemporaneous, confidential conversations with Taiwanese and local officials. Chinese companies hold a significant position in Kiribati’s most important industry, from which the government receives the majority of its revenue. Other factors highlighted in this analysis also trend in Beijing’s direction: tuna can be sourced from other countries and is not a strategic good, investment from other countries was not forthcoming, and domestic politics favored Beijing. Together, these factors resulted in apparent influence over policy behavior, without the need for economic coercion.

Case Study 2: Grain Transport in Romania

Not all acquisitions or ownership by China-based entities around the world have resulted in influence, though they demand attention and deep scrutiny. For example, as part of a larger push to challenge the dominant position of Western grain traders in the global market, the state-owned food trade and distribution conglomerate COFCO International acquired 51 percent of Nidera, a Netherlands-based grain trader, in 2014.44COFCO acquired the remaining shares in 2017. COFCO International runs the foreign commodities operation of COFCO Group. Eric Schroeder, “COFCO completes acquisition of Nidera,” World Grain, February 28, 2017, https://www.world-grain.com/articles/7793-cofco-completes-acquisition-of-nidera. Romania Insider, “Chinese grain trader boosts business in Romania by 50% and becomes market leader,” August 1, 2019, https://www.romania-insider.com/cofco-grain-trader-romania-business; Florentina Nitu, “COFCO Sees Five-Fold Profit Rise in 2020,” ZF English, August 10, 2021, https://www.zfenglish.com/companies/cofco-sees-five-fold-profit-rise-in-2020-20224111. Soon after, this company in turn acquired a Romanian grain terminal in the port of Constanța on the Black Sea, operated by United Shipping Agency SRL.45“United Shipping Agency S.R.L.,” Constanta Port Business Association, accessed June 22, 2023, https://portbusiness.ro/en/membri/united-shipping-agency-s-r-l/; Diplomat – Bucharest, “Nidera marks strategic acquisitions in Romania,” January 21, 2015, https://thediplomat.ro/articol.php?id=5821. COFCO’s acquisition also included three grain storage silos in southern Romania. Andrea Brinza, “Strategic competitors in search of China: The story of Romania and Bulgaria,” Middle East Institute, June 17, 2020, https://www.mei.edu/publications/strategic-competitors-search-china-story-romania-and-bulgaria. Still operating under the United Shipping Agency name, this terminal has served as the hub for COFCO’s operations in Romania and the region.

COFCO International has since developed into a top grain trader and exporter in Romania, where the company was the third-largest exporter in the first quarter of 2023.46Adrian Lambru, “COFCO România, la Gala ‘Companii de Elită’: Afaceri în creştere cu 34,5%” [COFCO Romania, at the “Elite Companies” Gala: Business increased by 34.5%], Capital, October 19, 2023, https://www.capital.ro/cofco-romania-la-gala-companii-de-elita-afaceri-in-crestere-cu-345.html. According to its website, COFCO International has nine silos, located either inland or along the Danube River, to facilitate the flow of grain from countries along the Danube to its terminal in Constanța, which has heightened importance as a major hub for Ukrainian grain exports following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.47Romania Insider, “Chinese grain trader boosts business in Romania by 50% and becomes market leader,” August 1, 2019, https://www.romania-insider.com/cofco-grain-trader-romania-business; Florentina Nitu, “COFCO Sees Five-Fold Profit Rise in 2020,” ZF English, August 10, 2021, https://www.zfenglish.com/companies/cofco-sees-five-fold-profit-rise-in-2020-20224111. COFCO’s position in Romania has been further supported by other Chinese entities that have integrated into the country’s transport logistics network, including the China-Central and Eastern Europe Investment Cooperation Fund, a state-owned investment fund that purchased a Romanian network of sixteen grain silos and logistics hubs, and COSCO, which has established freight transport routes in the Black Sea and within Romania.48“Constanta Express Block-Train in Romania,” COSCO Shipping Lines (Romania), February 9, 2021, https://world.lines.coscoshipping.com/romania/en/news/companynews/3/1. Together with local industry expert Brise Group, CEE Equity Partners Limited—created to advise the China-Central and Eastern Europe Investment Cooperation Fund—established Bristol Logistics SA in July 2019. “Bristol Logistics SA,” CEE Equity Partners, accessed June 22, 2023, https://www.cee-equity.com/funds/bristol-logistics-sa/.

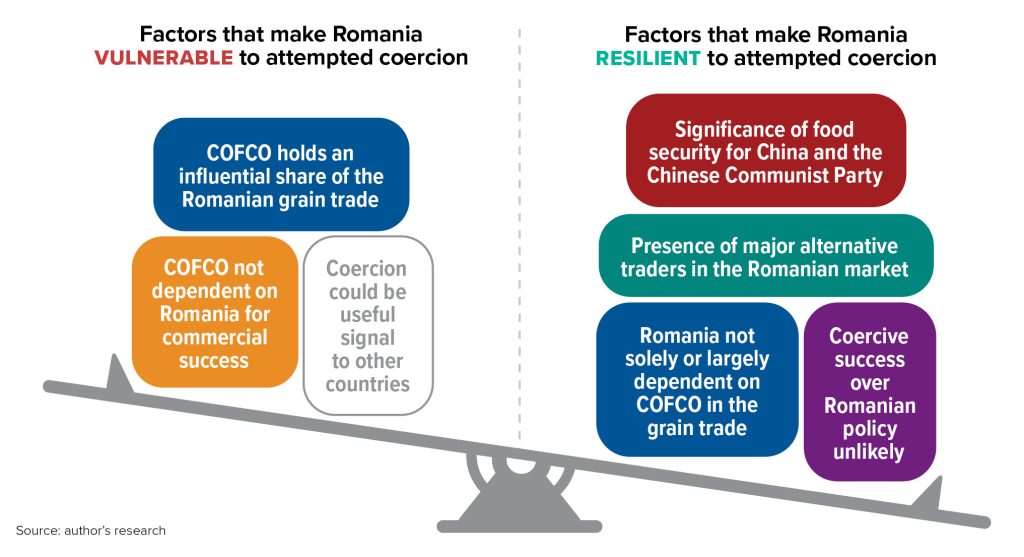

This integration of Chinese firms into Romanian and European grain transport and logistics networks raises the prospect that Beijing could use its connections to threaten, coerce, or influence policy in Bucharest and, through Romania, the European Union (EU), or the steady transport of foodstuffs from the Black Sea region. Yet despite COFCO’s position in Romania, there is no evidence to suggest Beijing has gained influence in Romania. Indeed, under conservative President Klaus Iohannis, Bucharest remains a staunch member of the EU and has resisted Chinese involvement in several significant projects and initiatives.49Matei Rosca, “Romania reveals the limits of China’s reach in Europe,” Politico, March 3, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/romania-recoils-from-china-aggressive-diplomacy/.

Several factors help explain why COFCO’s holdings in Romania have not resulted in the exertion of Chinese influence, coercive or otherwise. First, the presence of other major players in the grain market and Romania’s close alignment with Europe suggest that any attempt by China at coercion would likely fail to change Bucharest’s policies in Beijing’s favor. Romanian grain producers and traders have access to alternative traders and would be able to pivot away from COFCO, especially with EU support. If coercive success is in doubt, the costs of potentially losing COFCO’s operations in a major grain hub would likely exceed the benefits of punishing Romania or signaling Beijing’s displeasure over a specific policy issue.50Beijing’s calculus is of course also dependent on the importance of the issue in question.

Second, while grain exported through Romania is substitutable for China, domestic food security and the ability to fill any gaps through imports is an important issue for Beijing, and it is unlikely to risk losing access to global or regional markets.51Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “China Increasingly Relies on Imported Food. That’s a Problem,” Council on Foreign Relations, January 25, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/article/china-increasingly-relies-imported-food-thats-problem. Only if China could secure its own supply through other means and create negligible movement in global markets would COFCO’s position in the Romanian grain market be used as leverage in China’s economic statecraft. Moreover, a threat by China or COFCO to restrict global food supplies or otherwise create fluctuations in prices would go against Beijing’s declared commitment to South-South cooperation.52Aya Adachi, Jacob Gunter, and Jacob Mardell, “Economic stress has repercussions for China’s ambitions,” China Global Competition Tracker, MERICS, July 7, 2022, https://merics.org/en/tracker/economic-stress-has-repercussions-chinas-ambitions. While China has broken such promises before, Beijing is highly sensitive to accusations of abandoning developing countries.

Still, there are reasons for concern. China is by no means dependent on Romanian grain or regional grain exports through COFCO’s terminal in Constanța to guarantee its domestic supply. If Beijing felt secure in its ability to replace these foodstuffs, it is possible China could use COFCO’s position to make a coercive attempt to change Romanian policy. Such an attempt, likely through the slowing or suspension of imports, would leverage COFCO’s market share in a move similar to China’s informal measures against Australian exports. At the same time, the Romanian government’s resistance to past Chinese initiatives and its alignment with EU and Western preferences are policy positions that are similar to past targets of China’s economic coercion attempts.53Lithuania, for example, was also an EU member with relatively low economic vulnerability to Chinese trade and investment relationships that was willing to resist Beijing’s policy preferences. Despite China’s coercive economic campaign, Lithuania has yet to change the name of the Taiwan representative office, as Beijing has demanded. Through this lens, a theoretical coercive attempt by Beijing could seek not only a change in policy, but also to punish Romania for taking a policy position counter to China’s preferences or signal to other countries China’s willingness to use economic coercion.

The case of COFCO in Romania suggests that not all Chinese ownership abroad has resulted in coercion and influence or should be viewed only through this lens, even as the possibility very much exists. A number of variables come together to determine Beijing’s strategic interests in and ability to use these levers of influence, and they can either encourage or dissuade China from attempting coercion or influence. In Kiribati, these factors largely operated in China’s favor, but in the Romanian grain trade—at least to date—the potential costs of using COFCO’s connections for economic coercion have outweighed the benefits. Policy makers in Bucharest—and the EU—should remain wary of this possible vulnerability and continually assess the factors that expose Romania to the risk of Chinese economic statecraft.

Case Study 3: Container Transport and Logistics in Southeastern Europe and the Balkans

China’s past attempts at economic coercion vary widely, but trade is a common lever for Beijing to pursue its strategic goals. In these attempts, China either leveraged the strong market share of Chinese companies to pressure a target or instructed specific corporate entities to restrict economic exchange with the target.54China used its market power to restrict Lithuania’s ability to trade not only with China—which accounted for only about 1 percent of the Baltic state’s exports—but also with other countries, through threats against businesses that sourced materials and goods from the Baltic state. Konstantinas Andrijauskas, “An Analysis of China’s Economic Coercion Against Lithuania,” Asia Unbound, Council on Foreign Relations, May 12, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/blog/analysis-chinas-economic-coercion-against-lithuania. Against Australia, China took direct action by curtailing the import of specific goods in an attempt to pressure Canberra to cease its demands for an investigation into the origins of COVID-19. With this in mind, the strong and growing role of China’s shipping and logistics companies—much of it supported by BRI investment—represents a potential vulnerability for countries dependent on Chinese companies for freight transport. While Chinese investment and establishment of these logistics and trade routes thus far appear to be driven largely by commercial interests and a desire to secure China’s own supply chain security, they offer Beijing a ready-made mechanism through which it could seek to coerce or influence the policies of target countries.

As the leading Chinese SOE in shipping, COSCO deserves particular attention. The company’s growing share of global ocean shipping and port ownership is itself a worrisome development, with headlines focused on the possible security implications of COSCO’s expansive holdings.55Isaac B. Kardon and Wendy Leutert, “Pier Competitor: China’s Power Position in Global Ports,” International Security 46 (4) (Spring 2022): 9–47, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00433;Elaine Dezenski and David Rader, “How China Uses Shipping for Surveillance and Control,” Foreign Policy, September 20, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/09/20/china-shipping-maritime-logistics-lanes-trade-ports-security-espionage-intelligence/. Most recently, there was much concern over its minority investment in the Tollerort terminal in Hamburg, Germany.56Arthur Sullivan, “Germany inks deal with China’s COSCO on Hamburg port,” Deutsche Welle, May 11, 2023, https://www.dw.com/en/germany-inks-deal-with-chinas-cosco-on-hamburg-port/a-65586131. While significant, companies using the ports of northern Europe have plentiful substitutes to quickly pivot to the services of non-Chinese companies should China choose to use COSCO’s port holdings or its larger market share as tools of economic coercion.57COSCO also has a network of ports and intermodal rail connections in Spain. “About Us?” CSP Spain, accessed September 2, 2023, https://www.cspspain.com/en/empresa. COSCO’s European maritime connections are supported by COSCO’s regional transshipment company, Diamond Line, which allows the conglomerate to reshuffle goods within the European Union for easier and faster delivery. Container News, “COSCO transfers intra-Europe services to Diamond Line,” January 3, 2020, https://container-news.com/cosco-intra-europe-services-diamond-line/.

In Southeastern Europe, however, COSCO’s control of the Greek port of Piraeus and its port authority—as well as its intermodal rail connections through the region—affords the Chinese SOE a dominant role in the region’s freight transportation routes and the overall flow of goods.58Intermodal transportation of freight involves moving cargo using multiple modes of transportation, including any combination of truck, rail, plane, and ship. COSCO’s foray into Mediterranean shipping ports began in 2009, when a predecessor company (Cosco Pacific) won a bid to upgrade and operate one terminal at the Port of Piraeus through a thirty-year concession. COSCO subsequently bought a 51 percent controlling stake in the Piraeus Port Authority in 2016.59Piraeus was connected to the Greek railway system in 2013. This purchase included a provision allowing the SOE the right to purchase an additional 16 percent on the condition it completes a promised €300 million investment program within five years.60Jean-Marc Blanchard, “Plunging into Piraeus: Calming Excessive Positive and Negative Froth” in Chinese Overseas Ports in Europe and the Americas: Understanding Smooth and Turbulent Waters, ed. Jean-Marc Blanchard (London: Routledge, 2023). Despite failing to reach its promised investment goals by the 2021 deadline, the Greek state and parliament allowed the sale to go through.61Kaki Bali, “In Greece’s largest port of Piraeus, China is the boss,” Deutsche Welle, October 30, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/greece-in-the-port-of-piraeus-china-is-the-boss/a-63581221; Tasos Kokkinidis, “China’s COSCO Tightens Grip on Piraeus Port by Raising Stake to 67%,” Greek Reporter, August 22, 2021, https://greekreporter.com/2021/08/22/china-cosco-tightens-grip-piraeus-port/; Xiaochen Su, “Alleged state links will continue to hurt Chinese firms in Europe,” Asia Times, October 17, 2023, https://asiatimes.com/2023/10/alleged-state-links-will-continue-to-hurt-chinese-firms-in-europe/. Notably, the new agreement reportedly granted the Greek state a veto on strategic decisions, though it also reduced the number of state representatives on the Piraeus Port Authority’s board from three to one. Domestic Greek opposition has delayed COSCO’s development plans on numerous grounds, including labor disputes and failure to complete an environmental assessment for a planned cruise terminal.

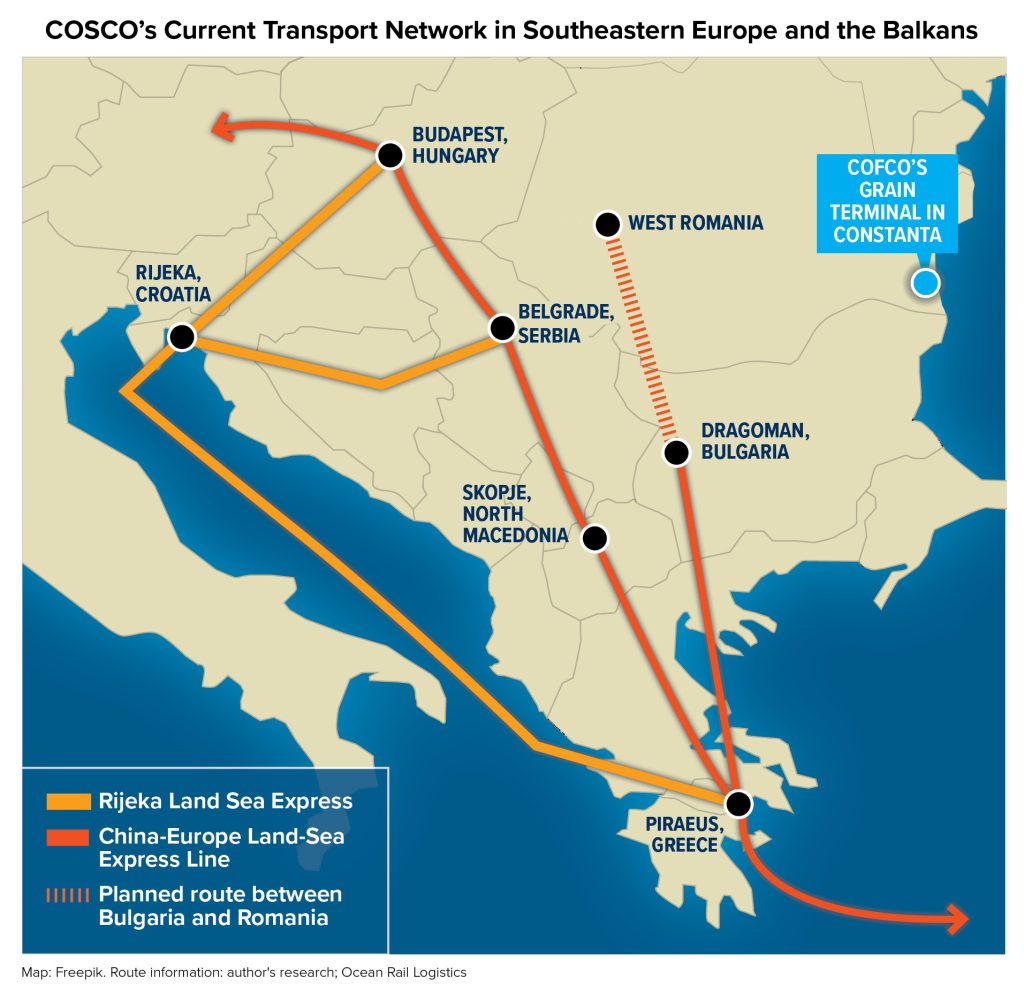

COSCO has since made notable investments in rail transport and is a vital operator in Southeastern Europe. The connections emanating from Piraeus—the port is now among the top six in Europe by cargo throughput—are part of the China-Europe Land-Sea Express Line (中欧路海快线), which coincides with the pan-European Corridor X running through Macedonia, Serbia, and Hungary.62Jakub Jakóbowski, Konrad Popławski, and Marcin Kaczmarski, “The Silk Railroad: The EU-China rail connections: background, actors, interests,” OSW Studies 72, February 2018: 16, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-studies/2018-02-28/silk-railroad. To upgrade the hinterland railways, China is financing a large portion of the Budapest-Belgrade railway line, with Chinese companies contracted to build part of the track. Ana Curic and Attila Kalman, “From Budapest to Belgrade: a railway line increases Chinese influence in the Balkans,” Investigate Europe, December 27, 2021, https://www.investigate-europe.eu/en/2021/from-budapest-to-belgrade-a-railway-line-increases-chinese-influence-in-the-balkans/. Ocean Rail Logistics also bought a 15 percent stake in Budapest’s Rail Cargo Terminal—BILK Zrt., Hungary’s leading combined transport terminal. “Ocean Rail Logistics S.A. acquires around 15% stake in Hungarian Rail Cargo Terminal – BILK Zrt.,” Rail Cargo Hungaria, accessed May 18, 2023, https://rch.railcargo.com/en/news/rail-cargo-terminal-bilk-ocean-rail-logistics-agreement. Through its subsidiary Ocean Rail Logistics (established in 2017), COSCO acquired a 60 percent stake in the Greek railway company Piraeus-Europe-Asia Rail Logistics (PEARL) in 2020.63Hellenic Competition Commission, Press Release – Clearance of OCEAN/PEARL Ltd, press release, March 27, 2020, https://www.epant.gr/en/enimerosi/press-releases/item/852-press-release-clearance-of-ocean-pearl-ltd.html; Laxman Pai, “Cosco Acquires Stake in Greek Intermodal Firm,” MarineLink, November 14, 2019, https://www.marinelink.com/news/cosco-acquires-stake-greek-intermodal-472918. Ownership of PEARL offered COSCO both access to the Greek domestic railway market as well as railway qualification in Europe. PEARL was only the third private rail carrier in the Greek market (along with Italian-owned TrainOSE and Rail Cargo Goldair). COSCO did not buy TrainOSE when it was for sale in 2016, however. In addition to its Greek network, PEARL operates in Bulgaria, Serbia, and North Macedonia.64“Pearl Group,” PEARL, accessed July 4, 2023, https://pearl-rail.com/pearl-group/. According to Ocean Rail’s website, PEARL is the only rail operator running freight trains from Piraeus via North Macedonia and Serbia to Central and Eastern Europe.65“Ocean Rail – About Us,” Ocean Rail, accessed May 17, 2023, https://ocean-rail.com/about-us/. In North Macedonia, PEARL accounted for around a third of total cargo volume transported by Macedonian Railways Transport, the public enterprise that operates all domestic lines, from 2019 to 2021 and 68 percent of total throughput in 2021.66Bojan Blazhevski, “China encroaches North Macedonia’s railroad sector [infographics],” Meta.mk, July 2, 2022, https://meta.mk/en/china-encroaches-north-macedonias-railroad-sector-infographics/; Railways of the Republic of North Macedonia Transport AD-Skopje, “Business Plan for 2022,” April 20, 2022, https://mzt.mk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Izmenet-Biznis-plan-1.pdf.

Ocean Rail also serves as an intermodal operator for Rijeka, a deepwater port in Croatia. In 2019, COSCO established a direct vessel shuttle between Piraeus and Croatia’s Adriatic Gate Container Terminal (owned by Filipino port operator ICTSI), and Ocean Rail has since introduced the Rijeka Land Sea Express, providing freight services to the hinterland markets of Hungary, Serbia, and others.67Ocean Rail, “ICTSI Croatia welcomes new intermodal service,” July 21, 2022, https://ocean-rail.com/ictsi-croatia-welcomes-new-intermodal-service/; Total Croatia News, “COSCO Launches New Shipping Intermodal Service Between Rijeka and Central Europe,” October 22, 2019, https://total-croatia-news.com/news/business/cosco/. Croatia, however, has expressed concern about Chinese involvement in Rijeka, ultimately cancelling a (non-COSCO) Chinese bid for the planned construction and operation of a new terminal for fear that China did not plan to actively use the facility and instead merely hoped to prevent others from doing so.68Warren P. Strobel, “In Croatia, U.S. Campaigned to Stop Chinese Bid on Key Port,” Wall Street Journal, April 2, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/in-croatia-u-s-campaigned-to-stop-chinese-bid-on-key-port-58c9bbff. After lobbying by the United States and the EU, the Croatian government canceled a 2019 concession for three non-COSCO Chinese firms to build and operate a new shipping container terminal in 2021. The subsequent rebid was awarded to a joint bid by two European companies: APM Terminals, a unit of the Danish shipping giant Maersk, and ENNA Logic, a Croatian logistic company. The campaign to cancel the tender included warnings that the agreement did not include guarantees for how much cargo would actually flow through Rijeka’s port. While Croatia has clear reasons for concern, the larger shipping picture in Southeastern Europe and the Balkans also demands attention. Future deals affecting the region’s container logistics networks should be met with equal scrutiny and clear guidelines for contractual obligations to ensure that COSCO or other Chinese entities do not gain undue influence.

Even without preferential access to Rijeka, Chinese companies—and COSCO specifically—hold a significant position in logistics networks in Southeastern Europe. COSCO’s controlling position in Piraeus and intermodal connections in Rijeka and throughout the region offer the conglomerate alternative shipping routes into Central and Eastern Europe. Not only are these countries increasingly dependent on COSCO for the shipment of goods and at risk of losing business associated with their transport, but COSCO then gains the credible ability to threaten to switch shipping routes and potentially allows China to hide strategic intent in commercial decisions. For example, COSCO could scale up shipping volumes through the Rijeka Land Sea Express at the expense of the countries in the overland PEARL connections.

This intertwining network—particularly if including COSCO’s connections in northern Europe—offers the SOE an increasing market share through which COSCO can manage trade flows through preferred channels. This growing dependence on COSCO could prove a significant pressure point for countries in Southeastern Europe and even the EU more broadly, and these logistics networks would not be easily replaced. Still, COSCO—and the Chinese party-state—have invested much in developing these logistics networks and would likely hesitate to risk them in a coercive attempt. The costs of exposing the China-Europe Land-Sea Express Line—an important success story in BRI connectivity efforts—could outweigh the benefits of using them as leverage to extract a policy concession. Yet as a means of influence, these networks could prove useful for Beijing and demand continued scrutiny.

Policy recommendations

These case studies offer a glimpse at the difficulty and importance of a full accounting of the reach and role of Chinese corporate entities in Beijing’s economic coercion and influence attempts. US policy makers can bolster their ability to counter Beijing through: 1) a nuanced understanding of the risks associated with Chinese engagement and the entities involved, 2) consistent communication with allies and partners to develop joint and complementary approaches to the challenge, 3) an appreciation for the concerns of countries most vulnerable to Chinese influence, and 4) a forward-thinking assessment of China’s future economic statecraft.

1) Investigate the economic involvement of Chinese entities around the world to better understand the associated risks and identify which projects may or may not pose a threat. Assessing the threat and responding appropriately requires a nuanced and comprehensive understanding of Chinese corporate entities, their acquisitions and subsidiaries, and their role in Beijing’s economic statecraft. Evidence that Chinese projects and investments can be harmful across a wide spectrum of issue areas is clear, as is the Chinese government’s willingness—if not always ability—to use the reach of China-based companies to pursue Beijing’s political goals around the world.

- Invest in long-term, in-depth investigations using varied data sources to make clear the extent of Chinese economic involvement. Open-source investigations into Chinese ownership, communication with the private sector, and local investigative journalism are critical sources of information regarding Chinese economic activities and their ties to the CCP. These efforts can bolster US governmental efforts, such as those of the Countering Economic Coercion Task Force established by the National Defense Authorization Act for 2023.69Zack Cooper and Allison Schwartz, “Five Notable Items for Asia Watchers in the National Defense Authorization Act,” AEIdeas, American Enterprise Institute, December 16, 2022, https://www.aei.org/foreign-and-defense-policy/five-notable-items-for-asia-watchers-in-the-national-defense-authorization-act/. Even with comprehensive data, links between Chinese corporate ownership and CCP influence, and the difference between commercial deals and strategic maneuvering, can be intentionally opaque. China often deploys economic influence that lacks transparency and verifiability, and many of the issue areas investigated here began with tips from experts on the ground. Expanding and cultivating local knowledge of Chinese financing and corporate practices, through education of community advocates, politicians, and investigators, will increase awareness of the costs (and benefits) of Chinese projects and empower these actors to more effectively engage and negotiate with Chinese institutions.

- Focus narrowly on economic activity that offers a channel for exerting influence. Deep skepticism is warranted of Chinese corporate ownership, even more so if the companies involved have verified ties to the CCP. At the same time, a healthy suspicion of Chinese companies and their business incentives should not equate to a vilification of all Chinese involvement. Even SOEs have incentives outside the political goals of the CCP. The challenge then is to identify areas in which the reach of Chinese companies offers Beijing the ability to alter policy decisions in targeted countries. This requires identification not only of the relevant companies and their relationships with various Chinese government entities, but also of their ability to use their market position to coerce or influence the target country’s policies. While this recommendation sets a high bar, the hope is to focus the expenditure of US and Western attention and resources on combatting Chinese corporate reach in industries and countries that are most vulnerable.

2) Coordinate with partners, most notably the EU and the Group of Seven. The United States is most likely to succeed in uncovering and countering Chinese economic coercion if it works closely with likeminded countries. Both the EU and the Group of Seven (G7) have expressed their concerns over Chinese coercion and influence,70The EU has put in place an Anti-Coercion Instrument to protect EU member states from “economic blackmail from a foreign country seeking to influence a specific policy or stance.” The instrument is not aimed solely at Beijing, though China’s coercive economic measures against Lithuania loom large. European Parliament, MEPs adopt new trade tool to defend EU from economic blackmail, press release, October 3, 2023, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20230929IPR06122/meps-adopt-new-trade-tool-to-defend-eu-from-economic-blackmail. and efforts at information sharing, supply chain resilience, and trade diversification should be pursued and implemented further.

- Share information on China’s use of economic coercion. China intentionally obfuscates aspects of its coercive measures and influence efforts to maintain plausible deniability. The web of Chinese entities is complex and multifaceted, and no single actor can readily piece together a complete picture. Among other agreements, the G7 Coordination Platform on Economic Coercion establishes a mechanism to collect this information under one entity and plan appropriate responses.71White House, “G7 Leaders’ Statement on Economic Resilience and Economic Security,” May 20, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/20/g7-leaders-statement-on-economic-resilience-and-economic-security/. This should include information sharing on specific Chinese corporate entities, their subsidiaries, and their role in coercive attempts to help identify future vulnerability, as well as transparency in contracts and MOUs. A more inclusive version of the platform could include EU and NATO members and US treaty allies; ideally, any country should be able to share their experiences with Chinese economic coercion, though, undoubtedly, political differences would make such a proposal unwieldy.

- Enact and expand de-risking measures, such as trade diversification and supply chain security. China has used trade ties, both large and small, in its coercive attempts. Given the country’s economic heft, trade with Chinese companies is unavoidable, but diversification reduces the potential effects of economic coercion. Likewise, reshoring and “friend-shoring” supply chains can help reduce dependence on China;72US Department of the Treasury, Remarks by Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen on Way Forward for the Global Economy, press release, April 13, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0714. part of these efforts should include scrutiny of Chinese corporate entities to help reveal economic security vulnerabilities.

- Reduce the impact of economic coercion through targeted support for allies and partners. After Lithuania’s experience with Chinese economic coercion, the United States offered economic assistance and diplomatic backing in support of Vilnius. In the past year, bills were introduced in both the US House of Representatives and the Senate in support of increased aid, decreased duties, and trade facilitation to foreign partners that are subject to economic coercion.73Countering Economic Coercion Act of 2022, S.4514–117th Congress (2021-2022), https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/4514/summary/00; Countering Economic Coercion Act of 2023, H.R.1135–118th Congress (2023-2024), https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/1135.

3) Take into account the interests and needs of emerging and developing economies when formulating US policies aimed at countering Chinese influence. Without sacrificing its foreign policy and economic interests, the United States should invest more time and energy in considering the needs of the countries over which it fears CCP influence. These countries—largely emerging and developing economies—are eager for greater engagement with the West; at the same time, they are uninterested in great-power competition and less receptive to Western messaging to avoid working with Chinese companies. Indeed, China is often meeting needs left unfilled by Western financiers and infrastructure developers. Without alternatives, these countries perceive a choice between accepting Chinese financing and forgoing needed infrastructure or development.

- Engage proactively with vulnerable states. The United States has been caught flat-footed on several occasions in the past few years. For example, Washington and its allies were left scrambling to react to Chinese influence in the Solomon Islands in 2021 and Panama in 2019. A robust, consistent, and fully funded US diplomatic presence is a (relatively) low-cost means through which to learn of these developments before they happen and consider US measures to counter Chinese influence.74Robbie Gramer and Jack Detsch, “The State Department’s China Shortfall Revealed,” Foreign Policy, July 25, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/07/25/state-department-china-budget/.

- Offer alternatives and make the most of comparative advantages in areas such as transparency, due diligence, and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) assistance. Discussions as part of this report consistently revealed a desire for alternatives to Chinese financing and development, highlighting the degree to which emerging and developing economies perceive few options emanating from Western countries and institutions. The United States and its partners should work to provide competitive and sustainable offerings through enduring initiatives. The G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, for example, could prove significant, if given sufficient time and resources. Initiatives in support of transparency in contracts, due diligence of projects, and ESG—all areas in which the United States and its allies have experience—would help reinforce the benefits of working with Western partners.

- Emphasize trade and investment diversification to avoid undue vulnerability. For all countries wary of Chinese coercion or influence, there must be an emphasis on diversification. A key factor in vulnerability to coercion and influence is industry dominance within a country or region. Even in areas where China does not have superiority in some aspects of the production or transport process, Beijing has been willing to sacrifice its market share to punish, coerce, or threaten. It is unrealistic to expect countries to forgo economic relations with the Chinese market, but encouraging and helping these countries identify alternatives can help convince them to reorient their economies away at least partly from China.

4) Prepare for evolving Chinese economic statecraft. Economic links developed by Chinese corporate entities have been leveraged to enact coercive strategies—through collective market position in an industry and directives from the Chinese party-state to cut ties with specific corporations or countries. Beijing’s tactics, however, are continuously evolving. Informal secondary sanctions, as were used against Lithuania, are likely to be used to persuade other countries to apply pressure on the target country. The United States was an active supporter of Lithuania after China’s coercive attempts, and the lessons from that episode should be readied to be deployed elsewhere. Beijing is installing more formal mechanisms of economic coercion as well. For example, two US defense contractors have been placed on China’s Unreliable Entities List, setting up its possible use more broadly.75“MOFCOM Order No. 4 of 2020 on Provisions on the Unreliable Entities List,” People’s Republic of China Ministry of Commerce, September 19, 2020, http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/article/policyrelease/questions/202009/20200903002580.shtml. The Unreliable Entities List, along with an Export Control Law, are two measures where China’s extensive shipping interests could play a major role in future attempts at coercion or influence.76Frank Pan and Ivy Tan, “China Added Two US Companies to the Unreliable Entities List,” Sanctions & Export Control Update, Baker McKenzie, February 21, 2023, https://sanctionsnews.bakermckenzie.com/china-added-two-us-companies-to-the-unreliable-entities-list/.

William Piekos is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub. His research focuses on US-China competition for influence, Chinese economic statecraft, and alignment policies in developing countries.

Related content

This report was made possible by the support of Sayari. It is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The author is solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations.

The author would like to thank the Global China Hub, including David Shullman, Colleen Cottle, Kitsch Liao, Matt Geraci, and Caroline Costello, for their work in support of this project, as well as Wendy Leutert, Jacob Gunter, Eleanor Albert, and Scott Wingo for their guidance and contributions.

Image: REUTERS/Rodrigo Garrido