India’s second economic stimulus to fight the aftershocks of the COVID-19 outbreak is here at last. On May 12, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a much-anticipated expansion of the initial March 27 stimulus package. Modi broadly pledged to spend almost 10 percent of India’s fiscal-year 2020 gross domestic product—$256 billion—on economic relief measures toward building an “Atmanirbhar Bharat” or a “self-reliant India” in the devastating aftermath of the pandemic. The prime minister shrewdly left it to listeners to glean that the headline grabbing number of $256 billion would not be all new spending, and included the nearly $109 billion (43 percent of the total) in fiscal and monetary policy measures already implemented in the first stimulus.

It fell upon Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman to consequently go on air and provide the missing features of the latest spending initiatives, which she explained would be delivered in tranches. Sitharaman prefaced her remarks by touting the resounding success of the initial $22 billion fiscal stimulus, consisting primarily of cash transfers and food rations for poor families and women directly impacted by the lockdown. She appeared to be more tentative however in ascribing the same plaudits to the accompanying $87 billion infusion of cheap liquidity into the financial system by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to boost lending to micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), the country’s dominant job creator. Predictably, the RBI’s aggressive stance on monetary policy has barely made a dent so far in MSME lending. Parking surplus liquidity in financial institutions and expecting them to absorb the full credit risk from lending these funds to cash-strapped MSMEs, at a time when capital is scarce, has turned out to be a non-starter. Instead, financial institutions have deflected the excess liquidity away from much riskier MSME asset pools and parked it in safer, more profitable, higher-rated corporate securities.

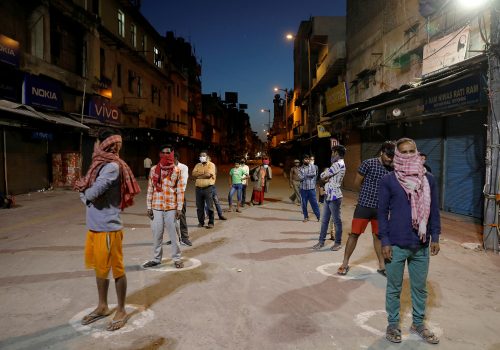

With the RBI monetary impetus turning out to be a damp squib and public anger mounting over the anguish of poor migrant workers fleeing unemployment caused by an extended lockdown, the finance minister unveiled a $55 billion spending scheme specifically meant to revive MSMEs and stem job losses. At the core, and by far the largest chunk of this package (73 percent), is collateral free automatic loans for MSMEs worth $40 billion, aimed at 4.5 million troubled—or what the finance minister alluded to as non-performing—small businesses with a turnover of less than $13 million and with loans outstanding of at least $3 million.

The scheme, which will run until end-October, will provide loans that are fully guaranteed by the government, for a tenure of four years with a twelve-month moratorium on principal payment. Fully guaranteeing loans to non-performing enterprises is a non-starter. Taking zero risk will only nudge lenders to refinance—at full cost to the exchequer—the past loan losses of these small borrowers, and use the remaining portion of this scheme to blithely, without examining any credit implications, build an asset portfolio of sub-standard companies. With full recourse to the sovereign and no collateral, the bill for payment defaults of most of these poor-quality borrowers will almost certainly have to be borne by the government.

The remaining $15 billion (27 percent) of the MSME rescue package focuses primarily on liquidity support initiatives to help troubled non-bank financial companies (NBFCs), who typically have large MSME portfolios. A partial credit guarantee scheme of $6 billion (40 percent of the $15 billion) has been created to encourage banks to buy investment-grade debt paper of NBFCs, with the government taking a first loss of 20 percent. For this type of capital market solution to work, however, there would have to be an active secondary market for banks to trade this paper in order to manage their liquidity risk, which is currently absent. Another special liquidity scheme of $4.0 billion (27 percent of the $15 billion) is also being launched to help NBFCs, housing companies, and mutual funds, but details on how this will be intermediated are yet to be revealed.

Other spending initiatives include capital funding for financially stressed companies. There is additional support of $2.6 billion (17 percent of the $15 billion), with a 20 percent first loss borne by the government, in the form of subordinated debt to be provided by banks for 200,000 MSMEs to improve their debt equity ratios. Equity funding of $1.3 billion (9 percent of the $15 billion) is also planned to be made available to viable companies via an MSME fund of funds. The need for this equity line is unclear since tenable companies are generally able lure private sources of equity on their own. Other relief measures for MSMEs include of $1.2 billion (7 percent of the $15 billion) of reductions in provident fund contributions to increase the take home pay of workers and fiscal support for employees’ contributions extended by another three months.

In the end, a relief package of $55 billion for the country’s biggest employer, which is less than half the size of the balance sheet of a large Indian bank, appears little more than symbolic. It’s centerpiece, the loan guarantee program, which transfers the full liability of loan losses of eligible borrowers to the exchequer, however, appears ill-conceived at a time when the government is scrambling to contain the fiscal deficit. Structuring the program to cover the credit and performance risks of MSME loan portfolios of financial institutions through risk participation or risk sharing would have been a wiser choice for the government. With lenders having skin in the game, expected credit losses would be lower with funds being deployed more sensibly to save viable, restructured companies. The government could further optimize its risk-adjusted return and expand the target market of borrowers under this program by leveraging highly rated, third party sponsors, such as multilateral institutions, to share the credit risk.

For beleaguered lenders, the last mile challenge of any government-sponsored scheme lies in its implementation. Very clear and detailed rules on loan loss collections have to be worked out upfront, in the event borrowers default, and lenders want to exercise their right of recourse. If there are delays or denials because of red-tape, financial institutions will steer clear of any government credit enhancement scheme, and troubled MSME borrowers will have to look elsewhere for a solution.

Ketki Bhagwati is a senior advisor to the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Further reading:

Image: A man wearing a protective mask walks past the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) building in Mumbai, India, March 13, 2020. REUTERS/Francis Mascarenhas