It’s not just tech-speak: Everyone has a stake in the supply of semiconductors. “Every aspect of human existence is becoming more digital… and everything digital runs on semiconductors,” explained Intel Chief Executive Officer Patrick Gelsinger, whose company is the biggest US chipmaker.

So the pandemic-driven disruptions to the semiconductor supply chain have an impact on everything from the auto industry to health care, and they won’t come to an end anytime soon, Gelsinger predicted at an Atlantic Council Front Page event on Monday hosted by the Council’s GeoTech Center.

This year “will remain a year of very constrained supply chains,” he said, and “we expect the shortages to continue into 2023.”

Below are more highlights from Gelsinger’s conversation with Fortune Media CEO Alan Murray.

Bending the chip curve

- In 1990, the United States produced 37 percent of the world’s semiconductors and Europe produced 44 percent; today those figures have declined to 12 percent and 9 percent, respectively. “We are now at a critical point where if we don’t shift this curve for the next decade, we can lose critical mass forever,” Gelsinger said. Asia’s market share has grown, he added, because of cheaper labor and larger government subsidies. “If there’s a topic that deserves the involvement of governments” to encourage competitive markets, “this is it,” Gelsinger said. “It is that important for every aspect of humanity.”

- The Intel chief supports Asian companies like the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company and Samsung beginning to build fabrication plants in the United States, which will help make US supply more reliable. But Gelsinger said that legislative efforts (a package of US Senate-passed economic competitiveness measures awaits action in the House) should be “preferential for US [intellectual property] and US companies” in how they hand out incentives. Still, “we are not waiting for governments,” Gelsinger said, explaining that Intel is currently packing more equipment into existing fabrication plants to boost semiconductor production.

❝We've seen that the lack of government involvement has resulted in this most critical resource moving to Asia over the last 30 years. If there's a topic that deserves the involvement of governments, it's industrial policy implementation.❞ #ACFrontPage

— Atlantic Council (@AtlanticCouncil) January 10, 2022

👤|@PGelsinger, @Intel pic.twitter.com/wN3ctZXTqF

- Looking into the future, Gelsinger warned that the shift toward Asia means “we have increasingly less influence on this most critical resource.” In shaping technology like semiconductors as “a force for good,” Gelsinger said it’ll be “essential” to partner with countries like Japan and South Korea who both lead in semiconductor production and follow democratic values. For example, “we should be agreeing on [a] shared view of export policies,” said Gelsinger.

The China challenge

- Gelsinger said that 25 percent of Intel’s revenue comes from China, and the company hosts manufacturing and research and development teams there. “If we’re going to be competing for world leadership, we have to participate in the fastest-growing market in the world,” said Gelsinger.

- Intel recently drew backlash from the Chinese public when it sent a memo to suppliers asking them to comply with the latest US laws—including a new law that prohibits goods made with forced labor in China’s Xinjiang province from entering the US market. Intel then removed the references to Xinjiang from the memo. “We found that there was no reason for us to call out one region in particular anywhere in the world because there [are] many regions in the world that are having issues of such a matter,” Gelsinger said. When asked whether Intel has stopped sourcing from Xinjiang, he said that the company “never had” done so. “We obey the laws of all jurisdictions that we’re in,” said Gelsinger, and because Intel is a American company, it regularly reviews its policies with the US government.

#ACFrontPage—@Intel CEO @PGelsinger addresses Xinjiang controversy: pic.twitter.com/d6Dpd74JOT

— Atlantic Council (@AtlanticCouncil) January 10, 2022

- He also noted that Intel will be finding ways to “do business effectively” in China while meeting US and “Western requirements as well. Heaven forbid that our political leaders wouldn’t allow us to find a reasonable Venn diagram overlap of those two worlds.”

Divine inspiration for good tech

- Whether coming from Asia or the West, Gelsinger said he believes that “technology is neutral,” but it is the job of tech leaders to ensure that technology creates a positive impact on “the length of life, the quality of life, the experience, [and] the learning,” of people around the world, in addition to helping eradicate poverty, end pandemics, and solve climate-change challenges. When asked whether achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 is possible, Gelsinger said yes, adding that leaders should do more than simply work toward that goal; they should try to beat it.

- Gelsinger noted that his Christian faith has fueled his mission to improve lives through technology. And he believes that encouraging Intel’s employees to express their religious beliefs or lack thereof is essential to ensuring that they each bring their “whole” and “best self” to the company. According to Gelsinger, that, in turn, will open the door to further diversity and inclusion around gender, sexuality, or culture. He noted that it was controversial in Silicon Valley in the beginning, and that he “was not as mature and thoughtful about the best way to do that earlier in his career.”

Katherine Walla is the assistant director of editorial at the Atlantic Council.

Watch the full event

Further reading

Mon, Jan 3, 2022

The United States must ensure semiconductor supply-chain resilience—not allocate short supplies

New Atlanticist By Robert Dohner

The current semiconductor shortage, now expected to persist well into 2022, stands out both for its longevity and consequences. The United States and its partners, like South Korea and Taiwan, can set the global standard for resiliency.

Tue, Dec 21, 2021

By the numbers: The global economy in 2021

New Atlanticist By

As the year comes to a close, our GeoEconomics Center experts explore the numbers behind the headlines that best capture the shape of the global economy in 2021—and what lies in store for 2022.

Thu, May 6, 2021

Chipwreck: Visualizing the downsides of semiconductors

EconoGraphics By Niels Graham, Josh Lipsky

The global chip shortage has impacted automakers far more than initially projected.

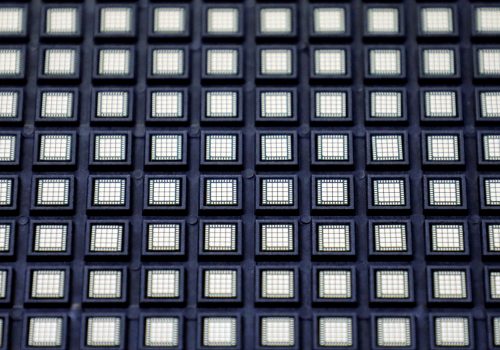

Image: FILE PHOTO: An Intel Tiger Lake chip is displayed at an Intel news conference during the 2020 CES in Las Vegas, Nevada, U.S. January 6, 2020. REUTERS/Steve Marcus/File Photo