US President Joe Biden’s defining framework for international affairs as a battle between democracies and authoritarian regimes has encouraged many US partners around the world, especially democracy and human-rights activists. Now Biden is rallying team democracy by inviting his chosen teammates to attend the Summit for Democracy from December 8-10.

The decision on whom to invite into the pro-democracy camp was always going to stir controversy. Biden has to balance admission based on the quality of a country’s democracy against more realist geopolitical considerations. Last week, the Western Balkans exposed this tension for all to see.

According to a preliminary list published by Politico, Belarus, Hungary, Serbia, Turkey, and Bosnia and Herzegovina were not invited to the summit. Kosovo wasn’t either, and its exclusion was surprising because it is both an increasingly vibrant democracy and a US ally. In response, leading Kosovo-based pro-democracy non-governmental organizations applied pressure. Kosovo’s President Vjosa Osmani also traveled to Washington along with Kosovo’s informal ambassador, pop star Dua Lipa, who spoke of a peaceful and democratic country before an influential crowd at the Atlantic Council’s Distinguished Leadership Awards. The US government course corrected soon after: Both Kosovo and Serbia, its longtime foe, received invitations.

In Kosovo’s case, the reversal made sense. While the rule of law and ethnic relations remain a challenge there, the country has bucked the authoritarian trends of recent years. It has held several free and fair elections, followed by smooth transitions of power. There is a vibrant and pluralistic media scene, although political influence remains a concern. Civil society is vibrant, and youth and women have become a key voting bloc. With that power, they are promoting change by advocating for rights and freedoms. From a foreign-policy perspective, Kosovars remain overwhelmingly staunch supporters of the transatlantic alliance, despite Russian and Chinese influence in the Western Balkans.

By failing to recognize Kosovo’s democratic performance with its initial snub, the United States was undermining its own goals to incentivize democratization across the Western Balkans as a means of advancing the region’s Euro-Atlantic integration. One of the reasons why the European Union (EU) accession process has stalled is that many in the EU are reluctant to admit new members on a similar trajectory as Hungary. But the current Western policy of embracing authoritarians in the Western Balkans for stability reasons has helped entrench exactly that type of illiberalism across the region.

The Biden administration is rightfully worried that the region—overflowing with disputes like the one between Kosovo and Serbia that has simmered since Kosovo’s independence in 2008—is becoming more vulnerable to Russian disruption efforts and Chinese corrosive capital. Recent escalations in Kosovo’s north and threats of a new conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina have raised serious alarms.

Hoping to contain a deterioration, the Biden administration is deploying more high-level diplomats to the Western Balkans; expanding the scope of sanctionable offenses in the region; continuing to prioritize the reduction of dependence on Russian energy sources; and encouraging regional cooperation, including through the Open Balkan initiative. But this approach also treats Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić as a valuable, if not always reliable, partner in striving for US goals, despite his role in facilitating Chinese and Russian influence in the region.

Osmani and Kosovo’s Prime Minister Albin Kurti came to power this year promising to fight corruption and to reject compromises with Serbia. They are perceived as being uncomfortable with the current US approach to the region, viewing it as too accommodating to Serbia at the expense of US allies. As a result, they have adopted a more assertive sovereigntist posture, undertaking several actions that conflict with US priorities, perhaps to force a change in course. This includes being uncooperative in the dialogue with Serbia and snubs like rejecting a proposed US-financed gas pipeline from Greece.

Many in Kosovo disagree with the leadership’s foreign-policy approach. It does not appreciate Kosovo’s overall weak hand, critics say, and it fails to see that the United States is ultimately on Kosovo’s side. Washington is trying to consolidate Kosovo’s statehood even as it addresses a web of other complications threatening regional peace. This disagreement is feeding into wider public discontent that is already having political consequences: In last month’s local elections, Kurti’s party suffered setbacks.

So is the drama over? Maybe for the time being, but the issues raised by the episode are not going away. By correcting its first slight, the Biden administration has only further highlighted the difficult question that runs through the entire summit: Is this all about geopolitics or is it all about democratic values? Inviting both Serbia and Kosovo does not change the fact that the two countries are on different democratic trajectories. Indeed, the about-face opens new questions on criteria. It is arguably harder to justify keeping Bosnia and Hungary out now.

Still, the administration’s reversal on Kosovo is a welcome development that (among other things) will empower its civil society. With the withdrawal from Afghanistan, Biden signaled a more realistic posture rather than a return to the liberal internationalism of the 1990s. That doesn’t mean he shouldn’t showcase the achievements of that era. Kosovo, with all its flaws, is one of the rare successful cases of US intervention and state-building, and its participation in the summit is a good thing. The summit will help in sustaining the momentum for domestic reforms, while also potentially resetting US-Kosovo relations toward a common outlook and approach to resolving the dispute with Serbia. It may not be a completely new beginning, but it’s a helpful step.

Agon Maliqi is a policy analyst and chairman of the board of Sbunker—a pro-democracy think tank and new media platform based in Prishtina, Kosovo—as well as a former Reagan-Fascell Democracy fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy.

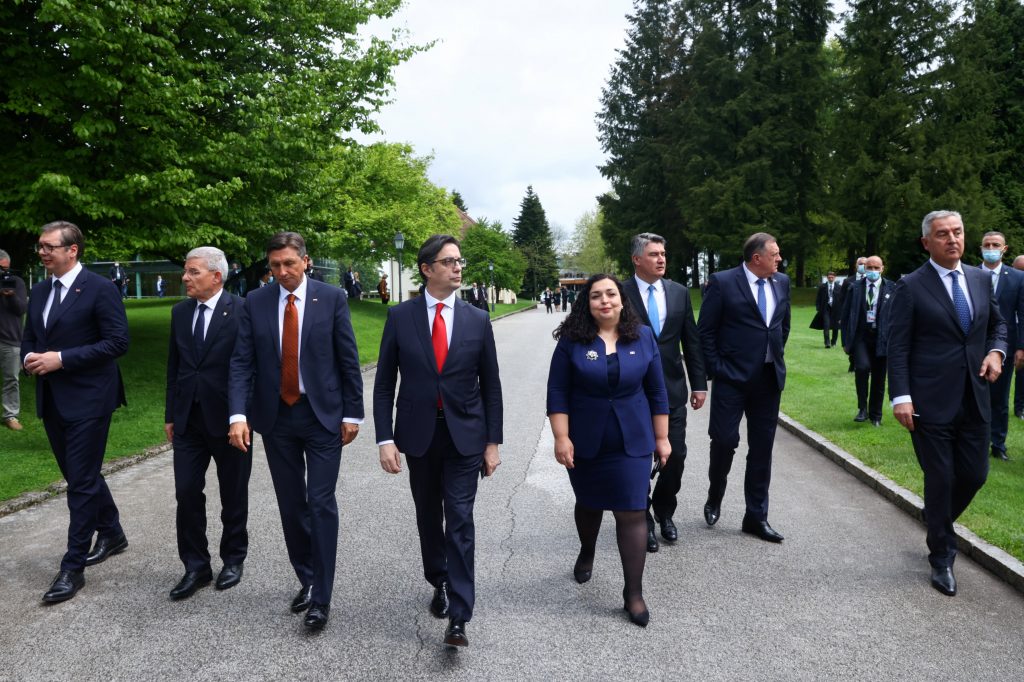

Image: President of Slovenia Borut Pahor walks next to his counterparts Zoran Milanovic of Croatia, Aleksandar Vucic of Serbia, Milo Djukanovic of Montenegro, Milorad Dodik, Sefik Dzaferovic, members of Bosnia and Herzegovina's Presidency, Stevo Pendarovski of Macedonia, Vjosa Osmani of Kosovo, at a park during the tenth anniversary of the Brdo-Brijuni Process, in Brdo pri Kranju, Slovenia, on May 17, 2021. (Photo by Borut Zivulovic/Reuters.)