Last week, the Biden administration made waves by moving to equally split the seven billion dollars in reserves of Afghanistan’s central bank parked in the United States between victims of the September 11 terror attacks and a trust fund for the benefit of the Afghan people. The reaction was swift and critical from many Afghan activists and commentators, with some calling the step nothing more than “theft.”

Their complaints are misplaced.

The administration’s actions since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan have sought to preserve funds for the benefit of ordinary Afghans—who are once again mired in a humanitarian crisis requiring international assistance—while at the same time acknowledging victims of Taliban-backed terrorism who hold legitimate claims.

To that end, the administration has been engaging in kabuki theater since August to ensure at least some cash makes it to the Afghan people. It has restricted the funds without formally freezing them under US sanctions against the Taliban. Calling it the Taliban’s money would have immediately opened it up to forfeiture in US courts; similar cases have proceeded quickly for victims of Iranian and FARC terror attacks.

If the administration were to release the full amount to Afghanistan, it would likely get bogged down in years of legal action because of such claims. So last week’s executive order was a deft regulatory step designed to keep the money in play for the Afghan people and give the administration leverage in negotiations with victims and courts. It uses presidential powers under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act to supersede the victim claims and place the funds under the administration’s direction.

This regulatory gambit has no guarantee of success, however, and the offer to split the funds appears to be a middle-ground approach the Biden administration hopes will avoid years of litigation in which no one benefits from the money.

Although wise, it is unlikely to satisfy Afghan activists upset with the administration’s decision to withdraw from the country, and who are now trying to make the best of an increasingly dire situation. Non-governmental organizations and other groups have long called for the United States to release all of these funds for return to Afghanistan in the hope that they would stabilize the country’s collapsing economy. But doing so would have made it easier for claimants to seize them; counter-intuitively, the legal limbo in which these funds have been stuck is what has kept them from being seized already.

Another unfortunate reality is that even sending the full seven billion dollars back to Afghanistan would not be enough to fix the economic catastrophe wrought by the Taliban’s return to power. As much as well-intentioned people want to build upon the modest progress made during the last twenty years, the US withdrawal removed the crucial security umbrella that gave private businesses confidence to operate. Many of those with expertise and experience fled the country, and the Taliban does not have the capability or the proclivity to run a modern administrative state.

Barring some major shift in the Taliban’s governing principles, it is a sad fact that private enterprise will be stifled under the group’s rule. Simply throwing money into an economic vacuum will not solve the problems the Afghan people face.

Like too many foreign-policy crises, there are no good options when considering how to dispose of these Afghan central bank funds. Indeed, in this circumstance there are not even marginal ones: They are all bad.

Meanwhile, US victims of the September 11 attacks hold legitimate grievances and claims against the Taliban—which currently controls the Afghan central bank and as a result would collect all the funds if they are simply released. Why should American victims be denied access to those funds when they have not received any recompense for the Taliban’s support of the worst-ever terror attacks in the United States?

On the other hand, that seven billion dollars was built up as reserves for the stability of the Afghan economy and its people during the last twenty years free of Taliban rule. Why should that money be subject to a court ruling over actions that occurred before it was earned?

Splitting the money may not be the result anyone wants, but sometimes, the best solution is one that gives everyone something—and no one everything.

Brian O’Toole is a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and worked as senior adviser to the director of the Office of Foreign Assets Control at the US Treasury Department. Follow him on Twitter @brianoftoole.

Further reading

Wed, Jul 15, 2020

Strategies for reforming Afghanistan’s illicit networks

In-Depth Research & Reports By

Authored in-house and advised upon by senior fellows Ambassador James B. Cunningham, Ambassador Omar Samad, Marika Theros, Javid Ahmad, and Fatemeh Aman, this report explores illicit networks in Afghanistan in the context of peacebuilding, democratic consolidation, and enhancing state capacity. It concludes by outlining several specific policy recommendations that will be necessary to combat the illicit networks in a manner that supports the durability of the ongoing peace process in Afghanistan and the continued consolidation of its fragile democratic institutions.

Thu, Jan 20, 2022

Pakistan’s ‘Praetorian’ state is a troubling model for a Taliban-led Afghanistan

New Atlanticist By

If the Taliban emulates Pakistan’s Praetorian model, it will further erode all work done to grow a healthy Afghan civil society and develop civilian institutions.

Tue, Feb 1, 2022

Afghanistan needs a political roadmap to reduce economic hardship

SouthAsiaSource By

Afghans in general are aware that inside the country the Taliban are in the driver’s seat, but the vehicle cannot go far without having other major constituencies onboard as part of a new social contract.

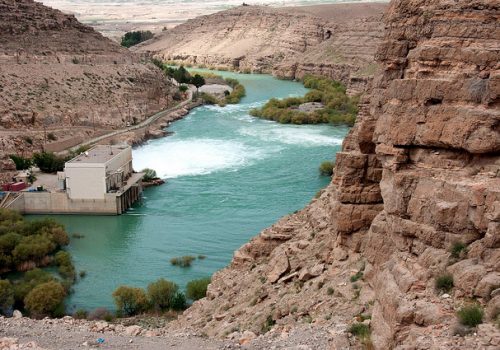

Image: Afghans line up outside a bank to take out their money after the Taliban takeover of Kabul. September 1, 2021. Photo by Stringer/REUTERS