President Donald J. Trump’s administration is not known for finesse. But in its December 14 sanctions against Turkey’s main defense-procurement entity (the “Presidency of Defense Industries” or SSB) for its purchase of the Russian-made S-400 surface-to-air missile system, it seems to have found a sweet spot: sanctions strong enough to capture Turkish attention but not so sweeping as to shut down bilateral security and arms relations with a NATO ally. The United States seems to be trying to manage a difficult problem, largely of Turkey’s making, while preserving overall relations.

In 2017, justifiably worried that the Trump administration might unilaterally remove US sanctions imposed after Russian President Vladimir Putin’s 2014 attack on Ukraine, the US Congress passed the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA). The act blocked unilateral administration rescission of sanctions on Russia and imposed additional sanctions, including (in CAATSA Section 231) secondary sanctions on third-country arms purchases from Rosoboronexport, Russia’s arms-export company. The legislation and the Trump administration’s executive order for that particular provision laid out a range of potential sanctions, ranging from relatively modest to full blocking sanctions. At least five of twelve options listed in the legislation had to be imposed.

In the case of Turkey and the S-400 system, the Trump administration chose from the more modest options available. The most significant steps the administration took included a prohibition on export licenses for any good or technology to the SSB and full blocking sanctions and visa bans on SSB Head Ismail Demir and three additional senior SSB officials. (The other three sanctions included prohibitions on loans or credits from US financial institutions and a requirement that the United States oppose international financial institutions’ loans to the SSB, restrictions that probably would not block other sources of funding.)

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s accompanying statement took a more-in-sorrow-than-in-anger approach: He noted that the United States had repeatedly urged Turkey not to purchase the S-400; referred to the earlier US suspension of Turkey’s participation in the F-35 fighter production partnership; and looked forward to consulting with Turkey to “resolve the S-400 problem,” thus allowing continued defense-sector cooperation.

This was the sort of measured response to an unwanted action by an ally that any US administration might have developed. The Trump administration preserved the credibility of Section 231’s deterrent power by going after a major ally. At the same time, rather than box in President-elect Joe Biden’s administration or create a crisis out of spite, the Trump administration officials who designed this response appeared to be trying to leave a door open for a resolution.

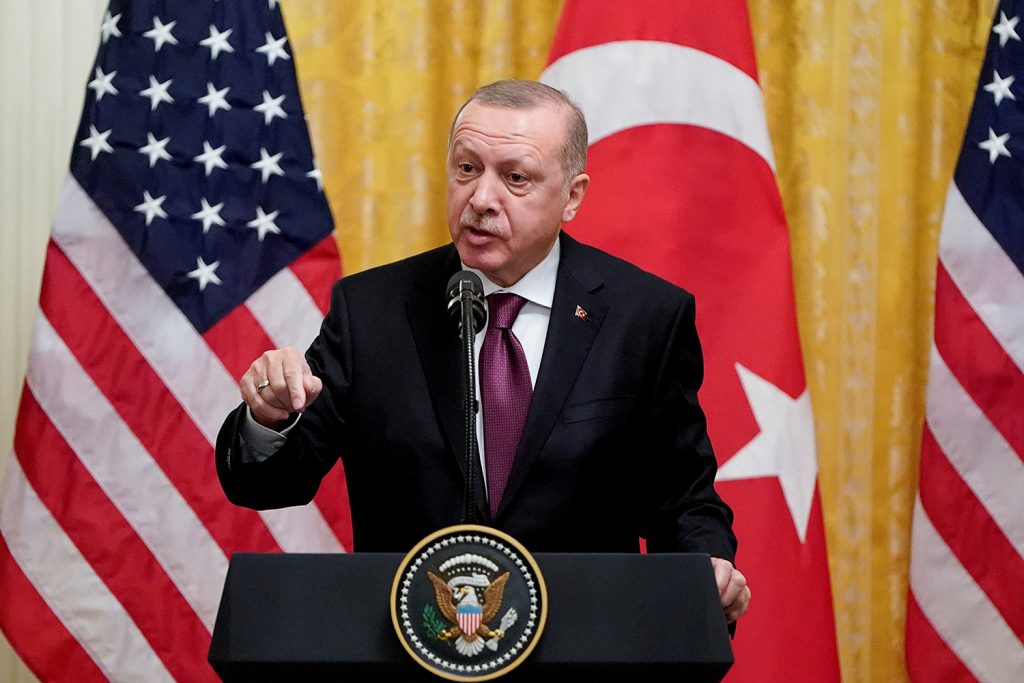

Whether Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan takes the opportunity is another matter. Turkish markets reacted to the sanctions with relative equanimity, recognizing that the United States chose the milder options available to it. Erdoğan reacted to the sanctions with anger, calling them an attack on Turkey’s sovereignty.

US-Turkish relations have been rocky for years. The high hopes for Erdoğan that former President George W. Bush’s administration had in the first years of Erdoğan’s AK Party rule are long gone and outreach by former President Barack Obama’s administration to Erdoğan early in its term is nearly forgotten. The causes are multiple and complex. They include the Obama administration’s slow reaction to the 2016 attempted coup against Erdoğan and Turkey’s concern over US relations with Kurdish groups in Syria. But there are other contributing factors—including Erdoğan’s alienation from his original (and more pro-Western) path, which he took together with AK Party colleagues such as former Turkish President Abdullah Gül, and his persistent championing of a sort of neo-Ottoman regional stance to replace Turkey’s Western orientation, which had been in place since former Turkish President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s time.

The incoming Biden administration may have a window of opportunity to turn relations in a better direction. By imposing the CAATSA sanctions before Biden takes office, and picking from the lighter end of the menu, the Trump administration has left its successor some room to at least try. The United States needs to do its homework and consider its own mistakes with Turkey and in the region. If the Biden administration reaches out, Erdoğan will have to decide whether to make a reciprocal effort, which will require movement from his side as well. Getting past the S-400 problem will not be easy. It’s a major piece of advanced military hardware and the United States is asking Turkey to give it up. But integrating it into an otherwise-NATO compatible military was bound to be problematic, as the Turks were surely aware from the start. Both sides will have to want to make relations better and be ready to act to that end.

CAATSA’s Section 231 was intended as a deterrent to third countries considering increasing their arms relations with Russia. It always had the potential for unintended consequences, but the Trump administration seems to have sought to minimize the risks. The professionals in the Turkish government probably know this. These latest sanctions are not the source of US-Turkish tension years in the making, nor do they prevent its resolution; and the sanctions are now out of the way, giving Biden and Erdoğan a possible window.

Daniel Fried is the Weiser Family distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was the coordinator for sanctions policy during the Obama administration, assistant secretary of State for Europe and Eurasia during the Bush administration, and senior director at the National Security Council for the Clinton and Bush administrations. He also served as ambassador to Poland during the Clinton administration. Follow him on Twitter @AmbDanFried.

Further reading

Image: REUTERS/Joshua Roberts/File Photo