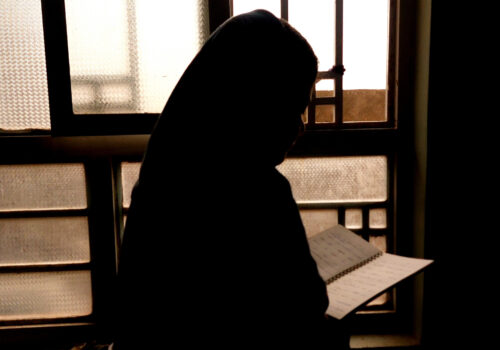

As the calendar turns to spring, no fewer than five holidays from different religions are more or less coinciding: Easter, Holi, Nowruz, Purim, and Ramadan. At the same time, the freedom of many around the world to practice their religion is increasingly threatened.

Earlier this month, the Pew Research Center released its latest report on global restrictions on religion. The report spotlighted the breadth and depth of challenges to religious freedom throughout the world. Amid ongoing threats to religious freedom, the time is ripe to consider how the US approach to this issue could be strengthened.

A difficult landscape for religious freedom

The Pew report is grounded in two indexes for gauging religious freedom conditions. The Government Restrictions Index considers “laws, policies, and actions that regulate and limit religious beliefs and practices,” while the Social Hostilities Index includes “actions by private individuals or groups that target religious groups.”

The report, which examines data through 2021, concludes that government restrictions reached a new peak that year, with harassment of religious groups and interference in worship the primary forms of restrictions implemented by governments. Harassment includes actions ranging “from the use of physical force targeting religious groups to derogatory comments by government officials.” Meanwhile, interference in worship includes “laws, policies, and actions that disrupt religious activities, the withholding of permits for such activities, or denying access to places of worship.” The report documented cases of worship interference in 163 countries in 2021, up 45 percent from 2007.

International religious freedom and US policy

The United States has long incorporated the promotion of international religious freedom into its foreign policy in some form, although the legal framework became more robust with the 1998 International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) and its more recent amendment, the 2016 Frank R. Wolf International Religious Freedom Act.

The IRFA established several institutions within the US government for advancing international religious freedom. This included:

- an ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom to lead an Office of International Religious Freedom at the State Department;

- a US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), an independent advisory body to monitor religious freedom throughout the world and make recommendations for US policy; and

- a special advisor to the president on international religious freedom, to serve on the National Security Council staff.

Furthermore, the US State Department and USCIRF are required to submit annual reports to Congress examining the state of international religious freedom. The State Department annually designates the worst violators as “countries of particular concern” and appoints other violators as members of a “special watch list.” The Frank Wolf Act added a designation for “entities of particular concern,” for designating nonstate actors. These laws also provide a framework for sanctions and other actions that can be taken in response to severe violations of religious freedom.

Improving the US approach to international religious freedom

Last year marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of IRFA. While there is much to be commended in the institutionalization of international religious freedom policy in the United States, the Pew report is a harsh reminder of the work that lies ahead.

What more can the United States do to advance religious freedom globally? To begin with, Washington should take full advantage of the legal framework already in place. For example, IRFA calls for the appointment of a specially designated official focused on international religious freedom on the National Security Council staff. Housed within the Executive Office of the President, this individual could serve as a critical point of coordination in the interagency process, working with Congress, the State Department, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and other entities to guide US policy. Regrettably, this role has been underutilized, to say the least. Only one person has served in it (during the Trump administration), and only for a brief period.

Moreover, presidential administrations have not leveraged punitive actions authorized by IRFA as effectively as they might. USCIRF has repeatedly criticized administrations for not designating certain countries as “countries of particular concern,” granting waivers on sanctions, or relying on preexisting sanctions. Certain severe violators are, therefore, either not held accountable for religious freedom violations, or they do not face new penalties specifically tied to those violations. Knox Thames, who previously worked with USCIRF and in senior State Department roles at the intersection of faith and global affairs, has argued for expanding laws such as the Magnitsky Act to broaden sanctions options and strengthen the ability to impose costs on malign actors.

The US government should reevaluate its approach to punitive actions for religious freedom violations and be prepared to enforce consequences through new sanctions directly linked to those violations. On the other hand, the reason existing law permits waivers is to enable officials to consider other factors in bilateral relationships. While punitive measures are a necessary element of the religious freedom toolkit, and there is room to improve how they are employed, a more diverse set of options is necessary.

One additional option to broaden the toolkit is grassroots engagement, working with civil society and faith-based organizations. There is some momentum in this direction. USAID, for example, launched a Strategic Religious Engagement policy in 2023, which “affirms the important role of religious actors as strategic development partners and provides a foundation from which the Agency can build and strengthen partnerships to advance shared priorities.” While not exclusively focused on religious freedom, USAID notes that “religious freedom and religious engagement are mutually reinforcing priorities.” Indeed, this sort of engagement provides a good opportunity to bring together diverse religious leaders around common humanitarian goals, fostering trust and a common stake in the wellbeing of their community.

Congress has already played a role in US international religious freedom policy through IRFA and the Frank Wolf Act. It should build on this by ensuring the various entities established by IRFA are adequately resourced and that USAID and the State Department can expand grassroots engagement with religious leaders and organizations to promote conditions on the ground conducive to greater pluralism and freedom.

There is no silver bullet to secure religious freedom throughout the world, but there are practical steps the United States can take to push back more effectively on the tide of restrictions.

Jeffrey Cimmino is the deputy director of operations and a fellow at the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Further reading

Thu, Nov 2, 2023

Faith leaders highlight Russian religious persecution in occupied Ukraine

UkraineAlert By

A delegation of Ukrainian faith leaders recently visited the United States and participated in a panel discussion to address Russia's policies of religious persecution and repression in occupied Ukraine.

Thu, Mar 21, 2024

Afghan women’s rights are not a lost cause. Here’s what the international community can do.

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

The United Nations must prioritize Afghan women's rights in its policy agenda and avoid forms of engagement that could embolden the Taliban.

Tue, Mar 19, 2024

Justice and accountability in the MENA region: The importance of women’s stories

Event Recap By

On Wednesday, February 14, the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Litigation Project hosted a hybrid panel event about the crucial role women and their testimonies play in pursuit of justice and accountability in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Image: Indonesian Christians are lighting up candles as they take part in the Christmas Vespers at Immanuel Church in Jakarta, Indonesia, on December 24, 2023. Millions of Christians in Indonesia are celebrating Christmas solemnly in the most populous Muslim country. (Photo by Aditya Irawan/NurPhoto)