Life after war: The impact of conflict on Syrian artists

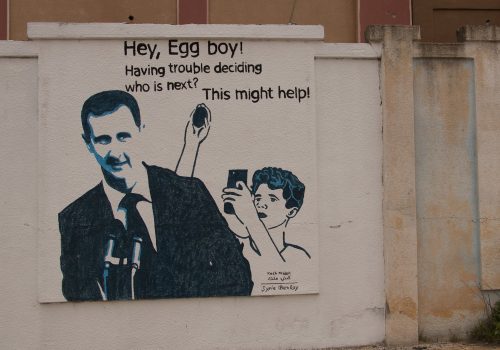

After a scrawled graffiti message in Daraa, Syrian artists began to express themselves more than they ever could since the Assad family took power. Revolutionary art exploded on to the global scene during the Arab Spring. Particularly in Syria, artists, writers, and filmmakers found a new voice, free of fear. Defiance, grief, and frustration were themes which carried through multiple forms of media from fine art to the written word.

However, eight years since the beginning of the revolution in Syria, the conflict which exiled these artists and, in some cases, brought them international fame, does not continue to define them as professionals. Conflict and the people affected by it are not stagnant or simplistic. Syrian artists are grasping with universal issues and connecting with broader audiences. The author spoke with artists Sulafa Hijazi and Tammam Azzam, as well as writer, Khaled Khalifa on their work and how they want to be interpreted.

Evolving artists

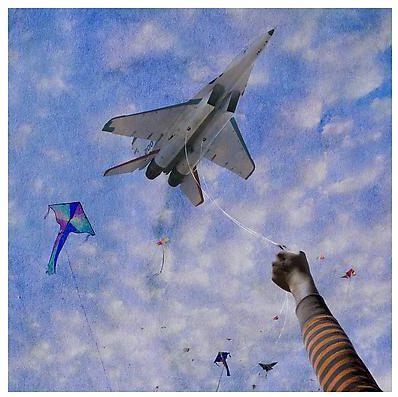

Now based in Berlin, Sulafa Hijazi is an award-winning visual and multimedia Syrian artist who also creates educational programming for children. In the heady days of the revolution, she published digital artworks that criticized political and social oppression. Upon leaving Syria, she felt an obligation to directly address the conflict since she believed that the media was missing the mark; overemphasizing the role of Islamists rather than civilians’ suffering and the desire to be free.

Her work aimed to redirect the narrative to reflect a more authentic experience for herself and others suffering from oppressive dictatorships. In doing so, she rebuffed US and Western policy’s focus on the Islamic State (ISIS) which shaped the lens in which most policymakers and Americans viewed Syria. The implications of this policy went beyond isolating Syria and Iraq as an ISIS problem to be fixed, but also changed the perception of those countries as bastions of extremism instead of victims of domestic and international terrorism.

However, these days, she does not want her artwork to be about her personal story or even the Syrian story. She wants her work to provoke universal human questions. Sulafa’s Ongoing series, which she launched online at the beginning of the revolution in 2011 is clearly tied to her identity as a Syrian but she “purposefully did not include pictures of the Syrian president or any elements related specifically to Syria in the series. I wanted this artwork to be about any conflict situation with accompanying humanitarian issues.”

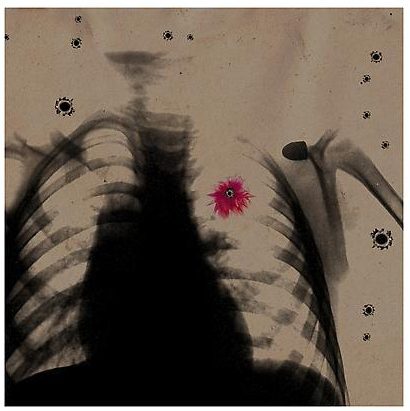

In describing her series Animated Images from 2016, Hijazi reiterated this idea. White, mannequin-like figures move from military training routines to the hypnotic inertia of being addicted to bad news according to the audience’s position around the piece. According to Hijazi, it is about our relationship with social media and media as makers and consumers. When violent images are ubiquitous, the violence becomes more accepted. According to Sulafa, this issue is universal; not just tied to Syria. Just as Syria is not a local conflict, but an international conflict, so too, is the normalization of violence in the media and the problems stemming from disinformation.

In the looped video installation Drops (2017), a grid of white lines on a black background appears as we see one of the artist’s digitized mannequin’s fall into the frame as a robotic voice says “checkpoint” and tells the viewer that higher levels are being reached as more figures seemingly collapse dead into a sub-grid. As Ned Carter Miles, the critic and UK Desk Editor for ArtAsiaPacific notes, “more and more bodies fall into adjacent grids, piling up in a confusingly flattened virtual space and poignantly suggesting the skewed mediatization of violence.” The universal application of this theme from war reporting to video games, to film and other media is obvious.

Revolution around the world

The Syrian artist, Tammam Azzam, classically trained in painting, blew up on the global scene with graphic design work tied to the destruction of the Syrian war. His piece, “Freedom Graffiti”, overlays Gustav Klimt’s famous work “The Kiss” on a building ravaged by the conflict. Since then, he has become renowned for his graphic design, painting, collage, and mixed media. For Azzam, the war in Syria is still a revolution. However, even though many of his works are clearly tied to the revolution and the consequences of conflict, he does not see his work as related only to Syria anymore. In exile, he has met many other artists who have fled conflict and persecution. As he put it, “the suffering is not just in Syria, it is around the world.”

The author, Khaled Khalifa, has gained international acclaim with his novels published since the start of the Syrian revolution, which have now been translated into several languages. In Death is Hard Work, Khalifa explores a family’s complicated past as they undertake an arduous journey through numerous checkpoints in a war-torn Syria with their deceased father in the back seat in order to bury him in his hometown. While this work takes place in Syria, he is grasping with universal themes.

Death is, after all, the most universal of human experiences, much like family disfunction. And in this novel, he explores both; how the death of a family member both unites a family and potentially conjures up pain, which has been left to fester. Whatever the internationally award winning author writes, it is now reaching a global audience. Critics have called it a “blackly absurdist road-trip novel, a restaging of [Faulkner’s] As I Lay Dying in the thick of the world’s most brutal civil war.” Khalifa explains that his most recent novel, No One Prayed For Them, which takes place in Aleppo in 1919, explores the universal themes of “love, hope and death.”

These artists do not intend to forget their past or their identity, but aim to make connections with audiences everywhere. The evolution of these artists from works uniquely tied to Syria to that which speaks to people from all walks of life is a natural part of an artist’s journey, but it is also a universal struggle for people trying to forge new ties in a new world.

Natasha Hall is an independent analyst specializing in the Middle East and refugee and humanitarian crises. Follow her @ArtInExileDC.

Related reads

Image: Syrian artist Moaffak Makhoul (top L) puts the finishing touches on a mural in al-Mazzeh neighbourhood in Damascus April 10, 2014. A group of Syrian artists in Damascus has created the world's biggest mural made of recycled materials, a rare work aimed at brightening public space in a city sapped by war and sanctions. The mural's lead artist, Makhoul, said the idea behind the project was to give ordinary people a chance to experience art and relieve some of the pressures of daily life as the country's three-year-old conflict grinds on. REUTERS/Omar Sanadiki (SYRIA - Tags: CONFLICT POLITICS SOCIETY TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY)