German Chancellor Angela Merkel has labeled the coronavirus pandemic the greatest global challenge since WWII. With the Western world embracing emergency measures and adopting policies of authoritarian interventionism unthinkable just a few weeks ago, it may also represent the most serious threat to the democratic gains of the past seventy-five years.

The sheer pace of the changes currently taking place is startling. One after another, countries are moving into lockdown in order to combat the pandemic. Entire economies are grinding to a halt. We are witnessing the failure of the liberal economic model that has dominated global affairs for the past few decades. Production chains are collapsing. International trade has dwindled. The thriving and hugely lucrative tourism, service and culture industries have virtually disappeared overnight.

Instead, countries are finding themselves compelled to adopt protectionist measures and rapidly expand their social spending as millions of citizens become suddenly jobless. The core principles underpinning modern liberal democracies have bowed to necessity as governments throughout the West increase direct state interference in the economy and introduce unprecedented restrictions on individual rights and freedoms. Few question the urgent necessity of these drastic measures, but nevertheless, the post-Cold War ascendancy of democracy, neoliberalism and globalism has never looked quite so fragile.

The rapid escalation of the coronavirus crisis in the European and North American heartlands of the Western world has been particularly striking. Inevitably, this is being compared unfavorably with the relatively successful policies of containment seen in Eastern Asia, with particular focus on the apparent effectiveness of the more authoritarian approach adopted in countries like China and Singapore. Such generalizations ignore the achievements of the region’s democratic poster boys such as Japan and South Korea. Instead, the mood of civilizational self-doubt is encouraging many Western observers to focus on stereotypes of authoritarian efficiency.

The specific policies employed in Eastern Asia’s fight against coronavirus are not as important here as the perception created within Western societies that a “strong hand” can provide greater security in exchange for some restrictions on liberty. Some authoritarian regimes are already seeking to exploit this sentiment, with Russia, in particular, making much of aid deliveries to coronavirus-hit Western countries including Italy and the US.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

For governments in formerly authoritarian Central and Eastern Europe, the coronavirus crisis promises to test the durability of the democratic transition that has reshaped the region over the past few decades. In societies still struggling with the legacies of the relatively recent totalitarian past, the pandemic is in danger of becoming an unlimited excuse that can be used to justify increasing restrictions on personal freedoms and greater intervention in different spheres of everyday life.

So far, the immediate need to fight the virus has proven far more compelling than the broadly liberal democratic values championed since the early 1990s. Nor is there any guarantee that the draconian measures imposed during the quarantine period will all be removed once the coronavirus threat subsides. Instead, fresh health scares or lingering coronavirus-related fears could be used to rationalize the indefinite extension of certain restrictions. A new brand of authoritarianism may emerge, taking the form of endless quarantine.

As a front line democracy, Ukraine is particularly at risk of backsliding towards authoritarianism. Public trust in the country’s dysfunctional democratic institutions is notoriously low, while nostalgia for an idealized version of the Soviet past remains widespread. In the current coronavirus context, this is a potentially potent combination.

The Ukrainian authorities have yet to impose a state of emergency in the country, but numerous prominent figures have voiced their support for such a move. With President Zelenskyy’s grip on power weakening, it is easy to see why an expansion of presidential authority might appeal. The Ukrainian leader looked unassailable following his landslide victories in the country’s 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections, but he recently lost his one-party majority in parliament amid growing internal divisions. As Zelenskyy’s personal status declines, those members of his inner circle who are currently pushing for a state of emergency will inevitably gain ground.

Other countries throughout the region are facing similar coronavirus challenges and choices. So far, Hungary is the only nation to openly abandon the democratic principles of the post-1991 settlement. However, others will no doubt watch Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s power grab with interest, and will also have noted the lack of an emphatic response from the European Union.

Eurasia Center events

Ultimately, the impact of the coronavirus crisis on the political climate will depend largely on how long today’s emergency measures remain in place. The extraordinary policies currently being pursued are justifiable in the immediate context of the pandemic, but they must be temporary in nature. Looking ahead, democracies entering the post-pandemic period will need to find the right balance between freedoms and responsibilities. The longer it takes to have this debate, the more deeply rooted the current restrictions will become. Historically, emergency measures have a nasty habit of becoming the new normal.

The coronavirus crisis is not the first challenge to the Western-led international order. Indeed, the 1990s triumph of liberal democracy and free-market capitalism has faced mounting opposition ever since the turn of the millennium as its shortcomings have been exposed and rival models have regained confidence. Nevertheless, the unprecedented global response to the current pandemic threatens to lend authoritarian forms of government a legitimacy not seen for generations.

Major international crises are traditionally catalysts for change. The current crisis is no different. It has the potential to tarnish the democratic values championed for the past thirty years while thrusting authoritarianism back into the international political mainstream. The best way to prevent this from happening is to look beyond the immediate task of combating the virus and emphasize the obvious benefits offered by societies based on individual freedoms and the rule of law. Authoritarian systems enjoy a number of specific advantages during times of national emergency, but they cannot compete with the quality of life available in the democratic world. If we lose sight of this, we will be recovering from the coronavirus crisis long after the pandemic itself has passed.

Oleksiy Goncharenko is a Ukrainian lawmaker with the European Solidarity party.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

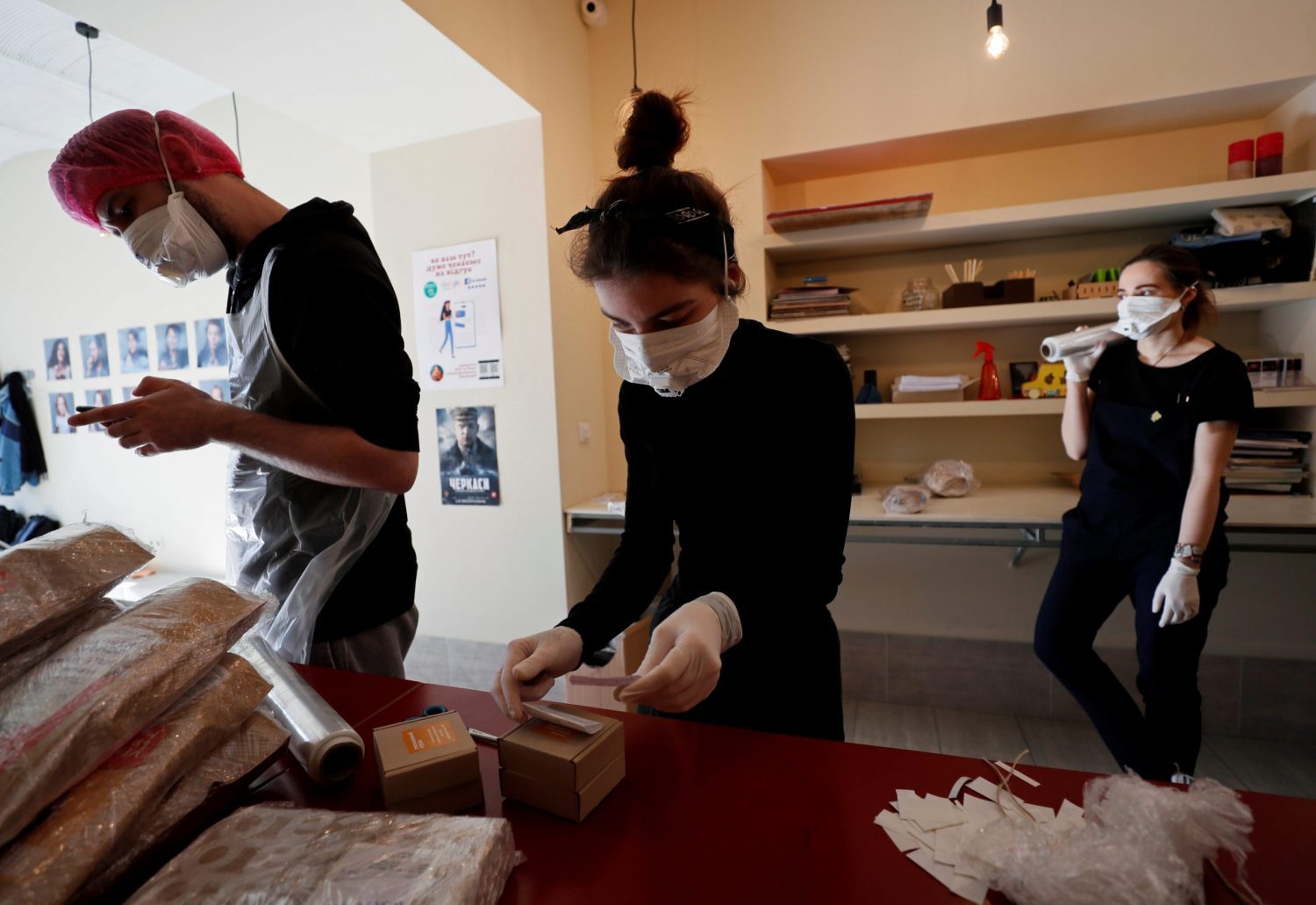

Image: A woman wearing a protective mask walks along Kyiv's empty main street Khreshchatyk. April 2, 2020. REUTERS/Gleb Garanich