Over the last six years, the unprecedented flow of Ukrainian labor migrants to the European Union has attracted a great deal of attention. However, this trend has yet to produce a comprehensive institutional response from the Ukrainian authorities. As the coronavirus lull gives way to a new wave of migration, now is the time for more coherent policies that can help Ukraine better understand the underlying issues driving labor migration while safeguarding the country’s workforce.

Since 2014, labor migration has become an increasingly important factor contributing to Ukraine’s economic growth. According to World Bank data, remittances to Ukraine in 2019 reached around USD 16 billion, which is more than 10% of the country’s annual GDP. Nevertheless, the outflow of workers is widely recognized as problematic, with local businesses often unable to fill vacancies and some of the most affected rural areas experiencing seasonal depopulation.

The issue has been on the political agenda since 2015, when the Ukainian parliament adopted the Law on External Labor Migration. This was followed by the 2017 Strategy of State Migration Policy until 2025, which contained a set of ambitious goals such as “creating the necessary conditions for the return and reintegration of Ukrainian migrants into Ukrainian society.”

Two years later, the incoming government of new Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy went even further and unveiled a range of specific measures to entice Ukrainian workers home. These included the creation of new jobs and the launch of long-term, low-interest loans for small and medium-sized businesses.

Then came the coronavirus crisis.

Following Ukraine’s decision to close the country’s borders, many labor migrants rushed home, creating a potential watershed moment for officials to take advantage of. However, despite talk from Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal of the government’s desire to keep returnee workers in Ukraine, a new exodus is already gathering momentum. Neither the lockdown nor the health-associated risks of working in manual, low-paid sectors deterred Ukrainian labor migrants from boarding the first charter flights to the United Kingdom, Finland, and Poland in May.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

At present, it is clear that the vast majority of Ukraine’s multi-million strong migrant labor workforce would rather return to the EU than take advantage of the various initiatives currently being offered by the Ukrainian authorities. Ukraine’s apparent inability to retain its workers will likely be further exposed in the coming months as many potential labor migrants are already eyeing the opportunity of working in Germany, which has recently relaxed its work permit rules for non-EU nationals. Back in 2019, 45% of Ukrainians working in Poland confessed that they were considering taking a job in another EU country, mostly in Germany.

The fact that Ukraine is struggling to keep hold of its workforce spells trouble for the country’s damaged economy. The causes of this negative trend include the seemingly perennial mood of distrust between Ukrainian society and the government, which serves to undermine official initiatives designed to encourage workers to come home. Meanwhile, widespread corruption and low salaries further complicate the matter.

The challenge currently facing the Ukrainian authorities is twofold. Kyiv must strike a balance between safeguarding the interests of workers travelling to the EU for employment, while at the same time looking to tempt them to build their futures in Ukraine without resorting to Soviet-style restrictions.

As Kyiv confronts the issue of the country’s departing workforce, it is not yet clear who within government has ultimate responsibility for labor migration policies and their implementation. Even though Ukraine’s Ministry for the Development of Economy, Trade and Agriculture officially oversees this matter, the Cabinet of Ministers and a selection of individual ministries are also regularly involved, as are local authorities across the country.

Most recently, the Deputy Prime Minister for European Integration was forced to step in and help coordinate the departure of chartered flights carrying seasonal workers to EU destinations. In order to correct this institutional confusion, the Ukrainian branch of the International Organisation for Migration has proposed the creation of “a powerful and effective coordination mechanism” between the various different government agencies.

Eurasia Center events

Another key task facing the Ukrainian authorities is the quest to understand why the country’s labor migrants believe the grass is always greener elsewhere. Is it really just a matter of higher salaries and better working conditions? Are long-term prospects a significant factor? What would convince these migrants to remain in Ukraine instead of departing? Serious research is required in order to identify answers to these important questions and draw the necessary conclusions.

The Ukrainian government could also consider launching detailed information campaigns about the pitfalls of working abroad. To date, there is no comprehensive guide available outlining the common hazards that Ukrainians may face when seeking employment in the EU, such as deportation or a lack of access to social security.

Labor migration is a long-term challenge for the Ukrainian authorities that they cannot afford to ignore. The good news is that the debate within Ukrainian society is already lively and the issue is high on the domestic political agenda.

In the months and years ahead, addressing Ukrainian labor migration will inevitably be a matter of trial and error. The government requires a far better understanding of the factors driving migration, and also needs to develop a much more coordinated institutional response. Ukrainian workers cannot be forced to remain in Ukraine, but the country’s future development will depend on its ability to convince enough Ukrainians that they have a bright future at home.

Lesia Dubenko is an analyst at Europe without Barriers, an NGO that specializes in issues related to freedom of movement, migration, visa policies and border security.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

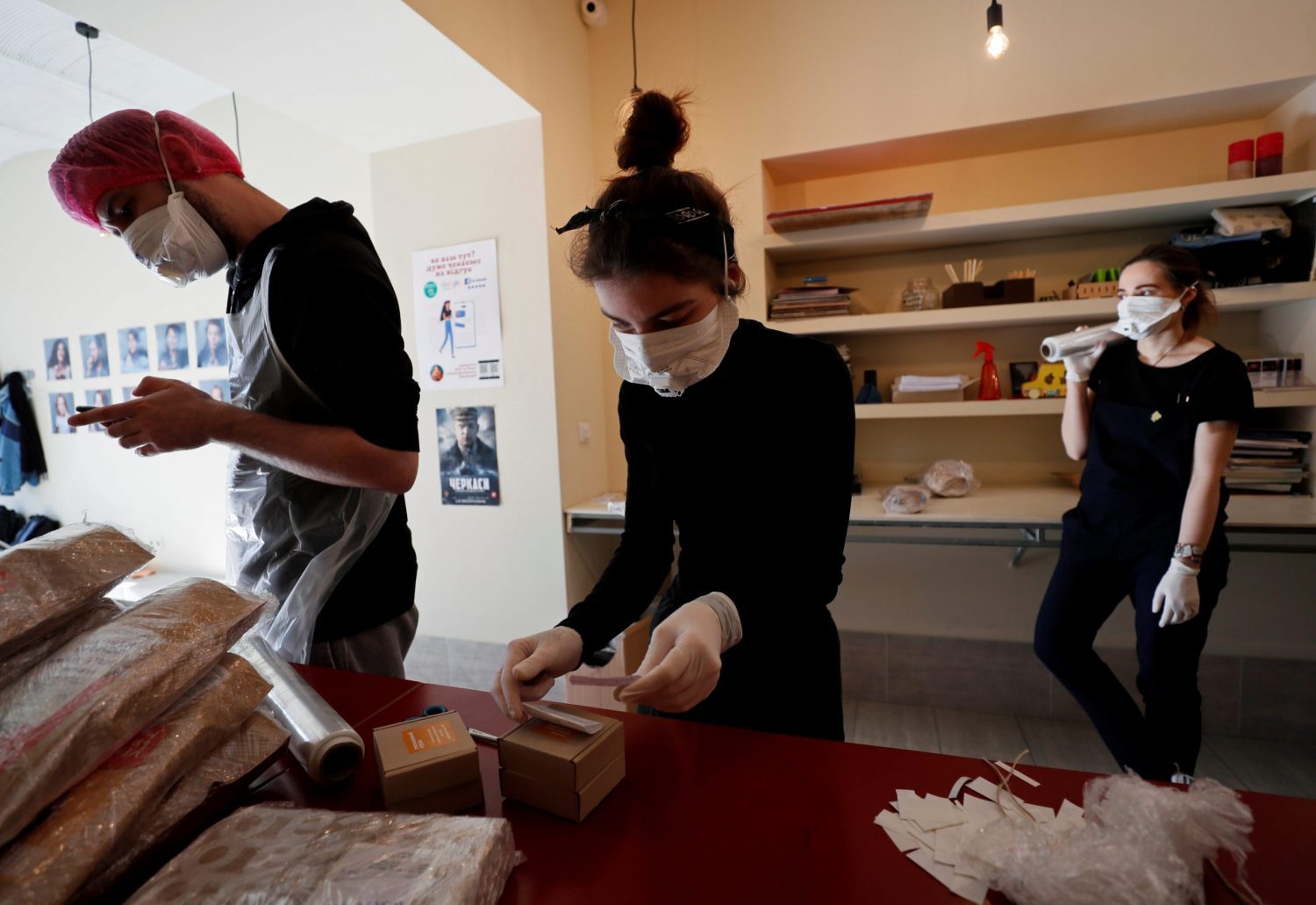

Image: Ukrainian workers prepare to fly to Poland from Boryspil International Airport. May 24, 2020. REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko