Make no mistake: As deadly and as disruptive as the COVID-19 pandemic is, this disease is a harbinger of even worse crises that could follow if a broader danger is not recognized. That danger is a new MAD: not the mutually assured destruction of the Cold War and the existential specter of thermonuclear Armageddon, but massive attacks of disruption.

Preventing or containing massive disruption to citizens, commerce, and communities must become the overarching consideration of the twenty-first century. Why massive disruption is so insidious and threatening is that as globalization, the diffusion of power, and advanced technologies dramatically raised global standards of living, new societal vulnerabilities were inadvertently created. It is these vulnerabilities that MAD targets and exploits. Unlike during the Cold War, when nuclear war was deterred, the new MAD is not easily deterrable.

Seven major disruptors beyond pandemics form the new MAD: climate change, social media, cyber, drones, terror, debt, and, perhaps the most dangerous, failed and failing government. Regarding failing government, on January 6 a mob, largely incited by the president of the United States, occupied the Capitol: It was not only an unprecedented assault on the US Constitution, but perhaps an act with political consequences more dire than those of the pandemic. And failed and failing government is not limited to the United States.

Of the other disruptors, climate change poses an existential danger to society. Had the cyberattacks launched against the US government, presumably from Russian sources, disrupted access for Americans to electrical power, water, food, the Internet, and cell phones for an extended period, the nation would have been thrust into chaos. Massive debt must be repaid. Terror lurks. And suppose the mob that violated Congress used armed drones, easily manufactured in basements and garages. How devastating would the carnage have been?

Amidst these dangers, what can be done as the Biden administration takes office?

First, recognition of MAD and its consequences is essential. For America, MAD has superseded the pursuit of great-power competition with China and Russia as the major foundation for its national security strategy. Yet that understanding is missing in action.

Second, President Biden has an immediate mechanism for dealing with the major crises he faces. Here, the advice of former President Dwight Eisenhower is relevant. When confronting a difficult problem, Ike would make that problem bigger to arrive at an appropriate solution.

The mechanism is the Biden proposal for a major infrastructure program. Obsolete American infrastructure—from the power grid to highways, bridges, air, seaports, and education—must be repaired and modernized for the twenty-first century. That alone, however, will be insufficient to meet and blunt the challenge of MAD.

Seizing on Ike’s advice, infrastructure must be expanded into a broader national reinvestment fund in part to stimulate biomedicine, renewable energy and sustainable environment, AI, quantum computing, cyber, 3-D printing, advanced materials, and other technologies with the purposes of rejuvenating infrastructure and the economy—and containing the new MAD. It is these technologies that will empower economic growth.

A national reinvestment fund would be seeded with about one trillion dollars in federal money and at least an equal amount from the private sector through the issuance of thirty-year bonds incentivized with 2 to 3 percent interest rates above prime, guaranteed by the government. The fund would be off-budget and repaid by user fees, tolls, and returns on investment. For those who doubt government can make, as opposed to print, money, the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) of about $800 billion, put in place after the financial crisis of 2008, returned an additional eighty billion dollars to the Treasury in interest payments.

The program should be named the “1923 Fund” since by 1923, following the 1918-1920 Spanish Flu pandemic, the United States entered into the greatest economic boom in its history and the Roaring Twenties. Fortunately, sufficient guardrails are in place to prevent the recurrence of the 1929 financial crash.

Electrification of the country and automobile production fueled that boom, accelerating productivity and creating massive demand for steel, rubber, gasoline, highways, bridges, restaurants, hotels, and other supporting infrastructure. Today’s parallels are universal access to 5G and broadband, as well as the technologies noted above. And national investment funds are applicable to most nations.

If the reinvestment fund is properly enacted, not every crisis will be resolved. But tens of millions of jobs and high rates of economic growth will be created, infrastructure will be modernized, and MAD will be contained. The ultimate tests will be overcoming the madness of a disunited United States, perhaps the president’s greatest challenge, and recognizing the real dangers of the new MAD.

This article was originally published by UPI and has been reprinted with the author’s permission.

Dr. Harlan Ullman is UPI’s Arnaud deBorchgrave Distinguished Columnist. His latest book, The Fifth Horseman and the New MAD: The Tragic History of How Massive Attacks of Disruption Are Endangering, Infecting, Engulfing, and Disuniting a 51% Nation, is due out this year.

Further reading

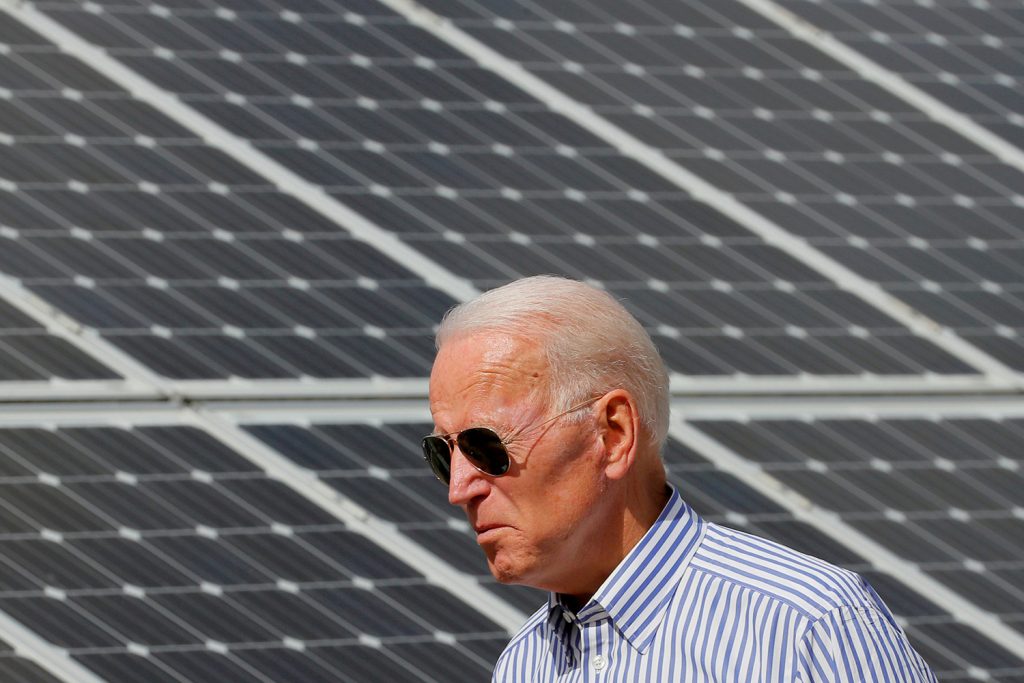

Image: Joe Biden walks past solar panels while touring the Plymouth Area Renewable Energy Initiative in Plymouth, New Hampshire, U.S., June 4, 2019. REUTERS/Brian Snyder/File Photo