A walk through Berlin: Thirty years after the Fall

Berlin is a city full of spectacular views. Here are some images I have grabbed on my phone in the neighborhoods my family and I have called home, often at night. They center on a strong tradition in Berlin: outdoor space decoration. Hardly any wall or surface is deemed interesting enough without added color. I’ve taken pictures while wandering around this great city, a place that resounds with history at every corner.

This is about the only building in this essay that is not being spruced up with added, new decoration—maybe it’s because it’s already filled to the brim with ornament. It is the Dom, built at the beginning of the last century by Kaiser Wilhelm II. He wanted Berlin to be the Protestant world’s answer to Rome and this to be its Vatican. It always grabs my attention on daily and nightly walks. It was very badly damaged by allied bombs during the Second World War, but restoration has been a local specialty.

Graffiti in Berlin is hallowed as a kind of divine right. Tour guides around my neighborhood stop with their crowds to explain the subtle signals, quips, and competitive dialogue between renowned artists as they cover public spaces in our park with their works. These two pictures are from Mauerpark, which means Wall Park. The Berlin Wall used to go along it, and the Wall itself was used as a vast graffiti canvas by those on the West side of it.

A night dog-walk along the Spree River just outside our home. Street artists aren’t picky about where to ply their works. On the other side of the water is Museum Island (which includes the Dom). The town is more than handsome and engaging by day, but lights at night tend to bring out something much more.

Looking across the Spree at Museum Island again, this is the Bode Museum, but likely you wouldn’t recognize it here. Every October brings the Festival of Light, where enormous, bespoke projections of all kinds of images are thrown onto buildings—this time not by individuals taking their own initiative, but rather the municipality itself.

This is the same Bode Museum facade, but this time adorned with some vintage imagery of Berlin’s iconic Brandenburg Gate, the city’s own Arc de Triomphe, and even more evocative ever since the Wall came down. That is because the Wall went right along it only a few feet away, sealing it off from free West Berlin and making it a symbol of the agony of the city’s ugly division: from the East one could get to the Gate but the Wall transformed it into a grand gateway to a dead-end.

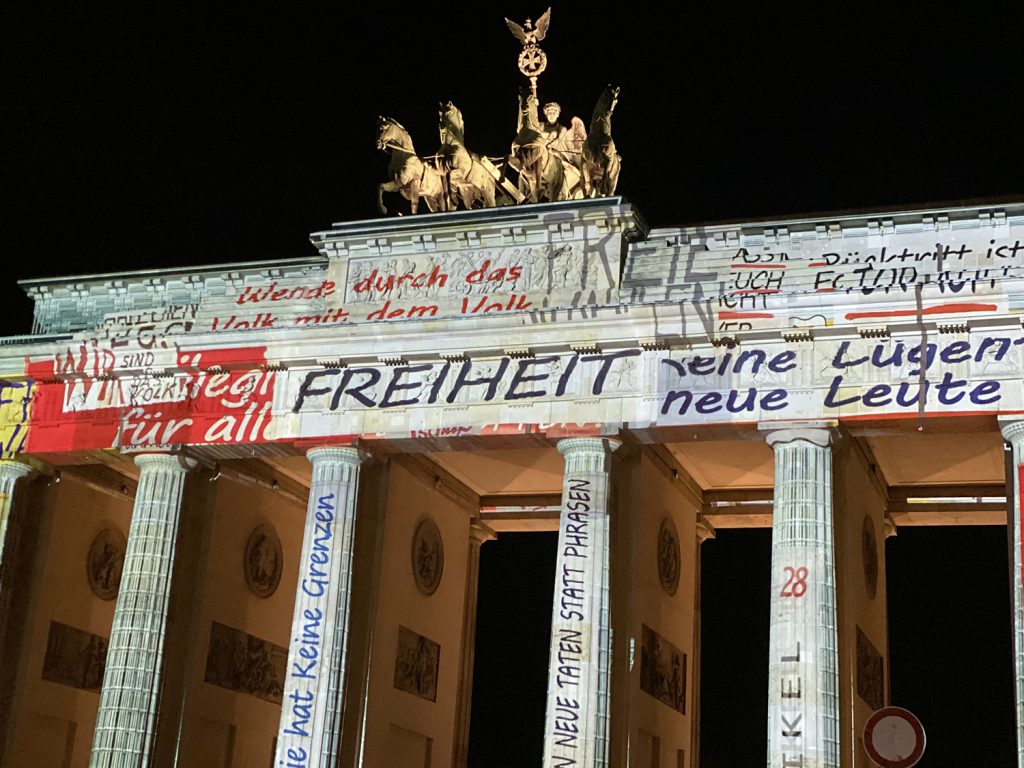

Here’s the real Brandenburg Gate, dressed up during the Festival of Light. In one of many pictures, films, and animations thrown onto it during the show. Here we see a newspaper headline from the 1980s quoting Ronald Reagan’s famous plea to Mikhail Gorbachev: “Tear down this wall.” And, exactly thirty years ago this week, they did. Better than that, a massive crowd of East Germans just streamed through it as the officials and guards stood by, unsure how to react. Not long after, the wall itself was torn down and history took a large turn.

“FREEDOM” is the simple message of this thirtieth anniversary—powerful and direct.

This is the image with which the light show climaxed and concluded, to a thrilled crowd, probably far more foreigner and other newcomers than those who could remember captivity on this side of that gate. In the three decades since Germany’s unification, memories of a divided city seem drowned out by the sheer international party energy which the whole place exudes any time of the day, week, or year.

Here’s the Dom, the building that I started this series with in its un-decorated glory. But during the Festival of Light even it cannot escape the gaudy glare of the projectors. The biblical reference in the text seems apt, although the party scene surrounding the event is as secular and free-spirited as the town forever seems to be.

John Dunton-Downer is a freelance documentary and videomaker living between Berlin and London.