Die Mauer im Kopf: The legacy of division in German politics

Key Points

- The far-left and far-right parties are taking advantage of lingering political differences between eastern and western Germany

- The political legacy of Communist rule means many voters in eastern Germany are often unmoved by the political arguments of the main centrist parties

- The growth of smaller parties could end the historical stability of German party politics, calling into question Berlin's ability to play a global leadership role

On October 27, 2019 the former communist party of East Germany, branded today as “Die Linke” (The Left) took the vast majority of seats in the Thuringian state election, followed closely behind by the far-right Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD). The result rocked a German political establishment accustomed to the dominance of the major centrist parties—the Volksparteien—and was further evidence of the destabilization of German politics, whose relative historical predictability allowed Germany to be a key leader in the EU and a staunch transatlantic ally. Pressures from a new global economy and rising rates of migration, however, have collided with the deeply rooted past of a divided Germany to make this stability a thing of the past. Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Germany is still grappling with a division— the Wall in the minds of the people, rather than an actual physical barrier of steel and concrete.

The end of the German two-party system

Since the creation of West Germany in 1949 the German party system has centered on two behemoths—the center-left Social Democrats (SPD) and the center right Christian Democrats (CDU) and their sister Bavarian party (CSU). In the middle of the spectrum were the Liberal Democrats (FDP), who often entered government in coalition with the CDU. It was not until 1983 that the Green Party came on the scene, and only assumed power in 1998 in coalition with the SPD.

The West German system was consistently stable compared to other democratic peers such as Canada, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Today, however, both major parties are on the decline and a number of smaller parties are gaining a larger share of voters at the polls. Part of the problem, as in other western democracies, is the convergence of party preferences. But the changing demographics of Germany—including the influx of migrants from other countries—and the evolution of the global economy away from a traditional working class towards a new digital precariat have produced difficult challenges for Germany’s main parties and spurred many voters to look for new options. These shifts, however, don’t tell the whole story.

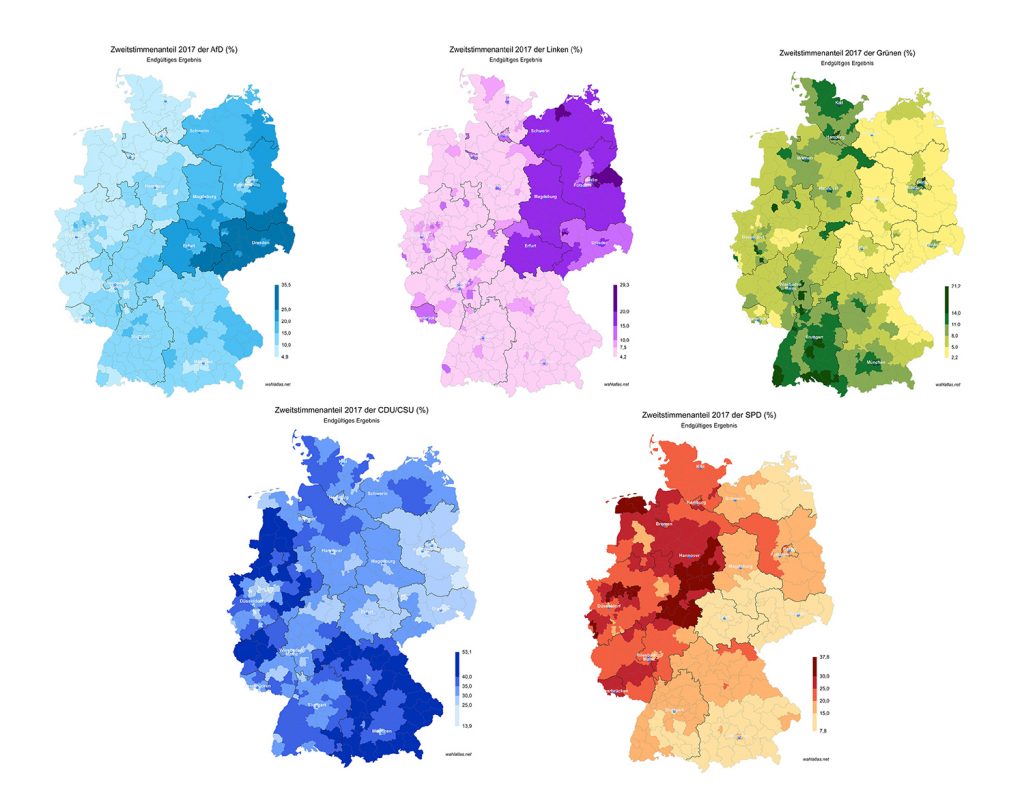

When one looks at voting patterns in the recent elections, the western half of the country is still dominated by the CDU/CSU and the SPD, with the Greens playing a larger and larger role whilst the FDP hovers in fourth place. The far-right AfD and the far-left Die Linke are relatively minor factors in western Germany. The story is reversed in eastern Germany, with Die Linke and AfD increasingly taking the top spots as the centrist parties fade. This is the legacy of a divided Germany and subsequent German re-unification in 1991. To understand what is happening, we need to understand how political evolution in the former West Germany and East Germany created this political division in the minds of their respective people that continues to endure despite re-unification.

Cold War cleavages

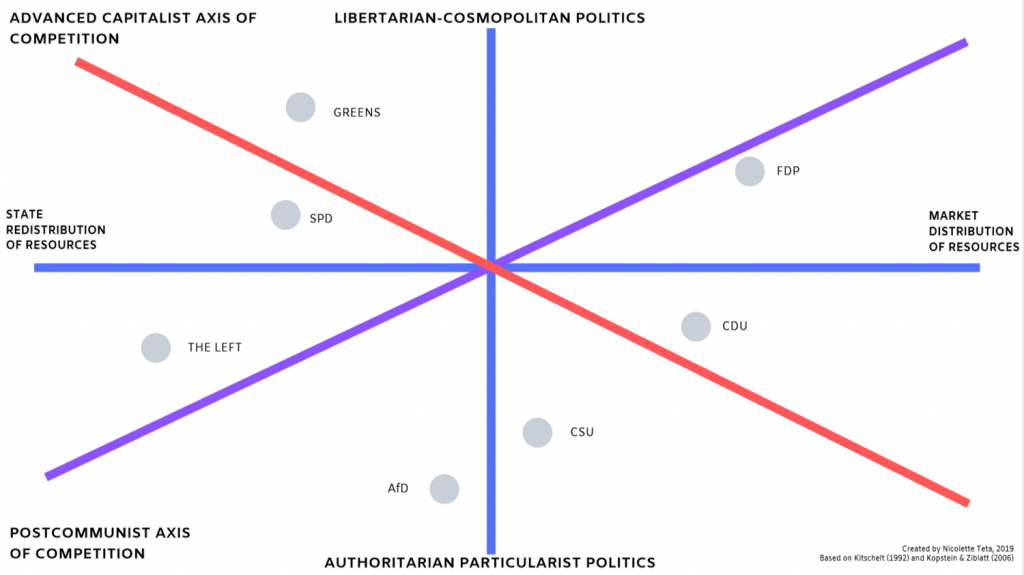

In 1992, Herbert Kitchschelt identified three primary cleavages that drive party politics—citizenship, procedure, and distribution.

Citizenship can be thought about as a spectrum, where one end accepts as citizens all individuals regardless of economic, social, religious, or racial attributes, while the other end bases citizenship on a particular cultural and socioeconomic homogeneity. Procedure cleavages deal with differences over the mode of democratic politics (hierarchical and centralized as in authoritarian systems vs. decentralized and participatory) and the scope of the process (open and collective decision-making vs. closed decision-making with limited input). The cleavage over the distribution is the most tangible aspect of politics, as at the ground level the running of society is based on the distribution of limited resources. The citizen’s control of resources is a hard, rather than abstract, aspect of society. In this cleavage the range is from advocates of state distribution of resources to those favoring open markets.

Why does this matter? Because political parties only have a certain amount of elasticity—they are constrained by their previous positions and change, when it occurs, takes a long time. Political parties born in the former West Germany will remain, generally, along the same cleavages as they have historically, which often puts them at odds with east German voters. Many in the former East Germany favor a narrow conception of citizenship and more state distribution of resources, given their historical experience in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). The stagnant social structure of East Germany resembled an early modern, rather than late modern model. Electoral appeals to voters in the west often fall on deaf ears in the east and vice versa. The rise of Die Linke and the AFD in the former East Germany reflects coherent party development along the political cleavages as they existed in the GDR. This is born out in recent German elections.

Two parallel social structures

In the last federal election (2017) the CDU/CSU and SPD took home 32.9 and 20.5 percent of the vote respectively—their lowest numbers in years. Meanwhile, the Greens and Die Linke held steady at 8.9 and 9.2 percent of the vote respectively and the FDP clocked in at 10.7. The real shocker was the AfD reaching 12.6 percent and earning seventy-six seats in the Bundestag. On the surface we see simply the decline of major parties and the rise of the far right. But, when one looks at a map of voter preference, a distinct geographical separation is present—Die Linke garnered votes in the eastern parts of Berlin and in a smattering of eastern German locales. AfD reached 20 percent in most of eastern Germany but fared far worse in western Germany. Meanwhile, the SPD was strong in central and northwest Germany, whereas the CDU was strongest in far western and southern Germany.

State-level elections in 2018 and 2019 also starkly illuminate the cleavages between east and west. In the 2018 elections in the western states of Bavaria and Hessen, the major political parties took a serious hit, whilst the smaller Greens and AfD increased their seats in the Landtag by fifteen and nine. In Bavaria, the CSU remained strong with 37.2 percent of the vote, but the second largest party were the Greens with 17.9%. The SPD fell to 9.7 percent, losing over ten percentage points compared to the previous election in 2013. In the new year, the 2019 elections continued to wreak havoc with the major political parties, but the secondary players shifted. The September 2019 state elections in Saxony resulted in a twenty-four seat gain for the AfD with losses of fourteen seats for the CDU and eight for the SPD. In Brandenburg, both the SPD and CDU lost seats, whilst the AfD gained 11.3 percent more of the vote from 2014 earning a total share of the vote 23.5, just behind the SPD at 26.2. The election year closed out with Die Linke netting the top spot in the Thuringia state election with 31 percent, followed by the AfD at 23.4 percent. The conservative CDU/CSU netted 21.8 percent and the SPD only managed a meek 8.2 percent.

While support for the two strongest parties dropped consistently in these three years of electoral results, the smaller parties who benefitted from these drops differed significantly in the east and west, mirroring each region’s historical political cleavages and demonstrating political coherence reflecting Germany’s division.

The Greens, for example, have made massive gains across the board but are strongest in the former West Germany and make up coalition governments in ten out of sixteen German states. In the former East Germany, however, the Greens receive a much smaller share of the vote, while Die Linke and AfD continue to grow. Preference for these parties often split depending on the voter’s definition of inclusive or exclusive citizenship, but differ between east and west due to these regions’ different historical conceptions of political processes and resource distribution. In the east, those with more exclusive “conservative-particularist” attitudes (i.e. Germany for the Germans) gravitate towards the AfD, while voters with a more open “liberal-cosmopolitan” preference break for Die Linke.

In the west, however, more “inclusive” voters break for the Greens and to a lesser extent the FDP, where those with an exclusive view of Germany move to AfD when alienated from the CDU/CSU. Interestingly, the AfD performs better in Bavaria, which may be because of the historical social legacy of the Catholic Church’s promotion of a decision-making space beyond popular democratic control for issues such as family and social welfare. The AfD is after all, not a product of the east—most of the key AfD leaders are from western Germany, but the AfD takes advantage of the eastern Germany’s historical political landscape. AfD may be strongest in the east, but there are also pockets of acceptance in the west, pockets that will undoubtedly grow as parties such as the CSU adjust to stop their decline.

A rough road ahead

In the case of Germany, past is certainly prologue. Despite extensive financial programs to integrate the former East Germany into the Federal Republic, critical differences still exist. This is because financial support can ease societal transition, but it does not necessarily change a mindset. Workers in both eastern and western Germany are challenged by the changing nature of the global economy and the rise of a more flexible labor market—but their prescriptions for dealing with these challenges diverges based on their historical socialization in the Federal Republic and the German Democratic Republic.

The Wall may have come down thirty years ago, but in the minds of many Germans one still remains. The result of this division will be an increasingly politically unstable Federal Republic. This does not mean a full political implosion, but rather Germany will begin to look more like the Netherlands or Sweden when it comes to forming governments. The political cohesion and stability of the more or less two-party system of the Cold War Federal Republic will be replaced by a more complex political map and require more compromise and political wrangling. This will mean smaller parties becoming more involved with governing. For example, the center-right has dominated Germany for over a decade, despite the fact that the center-left and left have a larger share of the seats in the Bundestag. The SPD, however, refused to form a coalition with the far left Die Linke. If the SPD, Greens, and Die Linke were to enter a coalition government, they could form a minority government. Given the near total collapse of the SPD, as well as the seasoning and moderating of Die Linke in recent years, the only hope for a SPD return to power will be via some such a coalition. This precedent already exists at the state level in Germany, where coalitions between Die Linke, the Greens, and the SPD govern in Berlin, Bremen, and Thuringia. Minority governments are not a feature of the German political landscape currently, but they will be soon and will reinforce the trend to political instability.

Pressure from these smaller parties won’t just change coalition arrangements, but also the older parties’ positions. The fact that the CSU failed to gain an absolute majority in the 2018 Bavarian state election was monumental, as voters flocked to the Greens and the AfD. Odds are that in an effort to staunch the flow of voters to the AfD the CSU will move further right, impacting national policies and further polarizing an ever flatter and broader electorate.

The result will be a more uncertain Germany, one that finds it harder to lead in Europe and that may become increasingly difficult to work with on the world stage. German leaders in the recent past may have said that Germany would welcome a new global leadership role, but the introduction of smaller parties to national coalition government will hamper this. The Greens are a generally pacifist party and their involvement in government will only add to German society’s already inherent tendency towards pacifism. Die Linke would likely complicate transatlantic relations. Leaving NATO seems a step too far, but some in the SPD are already sympathetic to Russia. A Die Linke-SPD-Greens coalition government would almost certainty mean a Germany less willing to fall in lock step with US foreign policy in east and central Europe. Germany’s role in NATO would also come under more scrutiny—especially given Washington’s constant battering of Germany under President Donald J. Trump’s leadership. Given that the CSU and to a lesser extent the CDU will need to move right to counter the AfD, Germany’s support of an inclusive, cosmopolitan Europe may become weaker. In short, all of the assuredness of past German predictability is out the window.

Allies of Germany need to carefully watch domestic politics as they play out in the coming years and must anticipate further instability. The good news is that although Germany’s democracy will become messier, it is a healthy, robust democracy. In both east and west there is acceptance of democratic norms and high rates of participation. In a way, the diversification of the German political spectrum improves the health of the system—if making it more unstable. The astute allied policy maker will anticipate these trends and work with the evolving German political party system, rather than against it.

The impact of Germany’s parallel political development during the Cold War will continue to be felt for some time. The physical wall that divided East and West Germany in Berlin may be gone, but die Mauer im Kopf—the wall in the mind—remains firmly in place.

Professor Michael John Williams is director of the Program in International Relations at New York University.

Further reading

Image: A pedestrian walks past segments of the East Side Gallery, the largest remaining part of the former Berlin Wall, in Berlin, Germany, September 19, 2019. REUTERS/Fabrizio Bensch