On October 23, Andrew A. Michta testified to the US Helsinki Commission. Below are his prepared remarks on Russia’s imperial ambitions in Central and Eastern Europe.

Thank you for inviting me to speak on lessons from Central and Eastern Europe when it comes to contesting Russia’s neo-imperial push into the region. Please allow me to enter these initial comments into the record.

Russia is a quintessentially revisionist state, aligned with China, Iran and North Korea—four states that together form an “Axis of Dictatorships” intent on overthrowing the international system put in place by the United States and its democratic allies after the Cold War. For over two decades, Russia has been relitigating the post-Cold War settlement, driven by its determination to restore the inner core of its former empire and establish a sphere of influence in Central and Eastern Europe and beyond. The war in Ukraine is not a sui generis event—it is a manifestation of Vladimir Putin’s drive to restore velikiy russkiy mir (Pax Russica) that is rooted in the fundamentals of Russian thinking about geopolitics and strategy that informed its formative experience as an empire. This strategic culture sees the empire as rooted in the Eastern Slavic core of three nations: the Great Russians, the Little Russians (Ukrainians), and the Belarusians.

Russian imperialism perceives itself to be in fundamental civilizational opposition to the West, the roots of which go back to the nineteenth century and the introduction of the official national policy that rested on three principles: the Orthodox faith, autocracy, and nationality (narodnost), whereby “nationality” meant walling off the empire from the West and fighting foreign influences alien to the Russia national ideal. The triad that came to be known as “official nationalism” became the dominant ideological doctrine of the Russian empire, generating the policy of russification in the nineteenth century of all non-Russian imperial lands. Today, there are persistent echoes of this ideology in Putin’s insistence that “there is no such thing as a Ukrainian nation,” and in his focus on “Eurasianism” as a pathway to de-westernize Russia.

Moscow’s overarching objective is to reconquer its “near abroad” by relying on military power to score geopolitical wins and restore itself as a great power in other theaters. This process began with the 2008 Russian invasion of Georgia, in the aftermath of which Moscow severed the provinces of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. It continued with the 2014 seizure and incorporation of Crimea, Moscow’s entry into Syria in 2015, and most recently with the second invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Even before Russia launched its military conquest, it had already been shaping the battlefield through information operations, cyberattacks, espionage and attempts at elite bribery and corruption with the objective of achieving partial elite capture.

As I have written elsewhere, Russia is already in phase zero of a protracted conflict with the West, targeting Eastern and Central Europe and the Baltic States as its near-term strategic objectives, and planning a long game to force the United States and its European allies to accept Russia’s status as a major power in Europe, entitled to an exclusive sphere of domination in Eastern Europe and a sphere of privileged interest in Central Europe, including in the countries that are members of NATO and the European Union.

At a risk of over-rationalizing history, I submit that there are striking parallels between the trajectory followed by Germany after its defeat in World War I and the road Russia has traveled since the end of the Cold War. In both cases, the dominant narrative produced for domestic consumption during the Weimar Republic in Germany and the Yeltsin decade in Russia was one of betrayal rather than defeat. In Germany, the Dolchstoßlegende, the “stab-in-the-back myth,” claimed that Germany was never defeated, but rather betrayed; in Russia, Putin has offered the population a similar narrative, blaming the West for the alleged treachery that brought down the Soviet Union.

I bring this up because that imperial narrative—much as it led to the rise of Hitler in Germany—continues to sustain Putin’s revisionism in Central and Eastern Europe. According to this view, the great Russian nation was robbed of its greatness by the United States and the West, and hence any action to remedy this perceived injustice is justified in the eyes of Russian imperialists. Hence, the threat Russia poses to Central and Eastern Europe—and to peace and stability worldwide more broadly—will not abate as long as the Russian revisionist narrative holds. Till then, Russia will remain a chronic threat to the United States and its allies.

Thank you for your attention. and I look forward to your questions and the discussion.

Further reading

Thu, Oct 24, 2024

Moldovan and Georgian elections highlight Russia’s regional ambitions

UkraineAlert By

Russia is playing a key role in elections currently underway in Moldova and Georgia, underlining Moscow's determination to retain its regional influence despite challenges created by the invasion of Ukraine, writes Katherine Spencer.

Thu, Oct 17, 2024

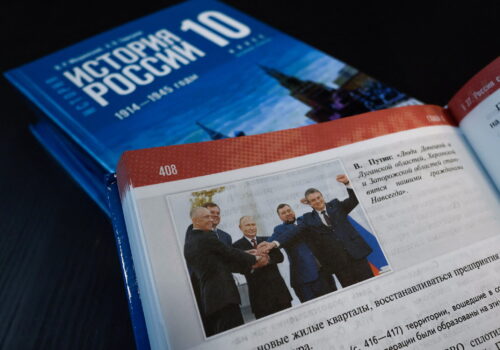

Russia is indoctrinating schoolchildren throughout occupied Ukraine

UkraineAlert By

The Kremlin is conducting a massive indoctrination campaign throughout schools in Russian-occupied Ukraine that underlines Moscow's intention to erase Ukrainian national identity, writes Tetiana Kotelnykova.

Thu, Sep 26, 2024

History is a key battleground in the Russian invasion of Ukraine

UkraineAlert By Benton Coblentz

Vladimir Putin has weaponized history to justify Russia's invasion of Ukraine. The international community can combat this by committing more resources to the study of Ukrainian history, writes Benton Coblentz.

Image: US Capitol Building is seen on Capitol Hill January 10, 2021. Photo by Aurora Samperio/NurPhoto.