Britons head to the polls on July 4 to elect a new parliament, which is likely to bring an end to fourteen years of Conservative Party rule. Our experts break down the elections and what they mean for the future of the United Kingdom (UK) and its role in the world.

Is the election result a foregone conclusion?

If the latest polling data provides any real indication, this election will give the ruling Conservative Party its biggest loss in more than a century, with the party set to potentially lose more than two thirds of its seats.

Labour, on the other hand, is currently projected to win by a 280-seat majority. Rishi Sunak may even lose his seat—which would be a first for a sitting prime minister during a general election.

The Tories have seen a lot in their fourteen years of uninterrupted rule: the “golden era” of relations with China under former Prime Minister David Cameron, the Brexit vote in June 2016, the COVID-19 pandemic that started in 2020, and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022—have all unfolded under a Conservative prime minister.

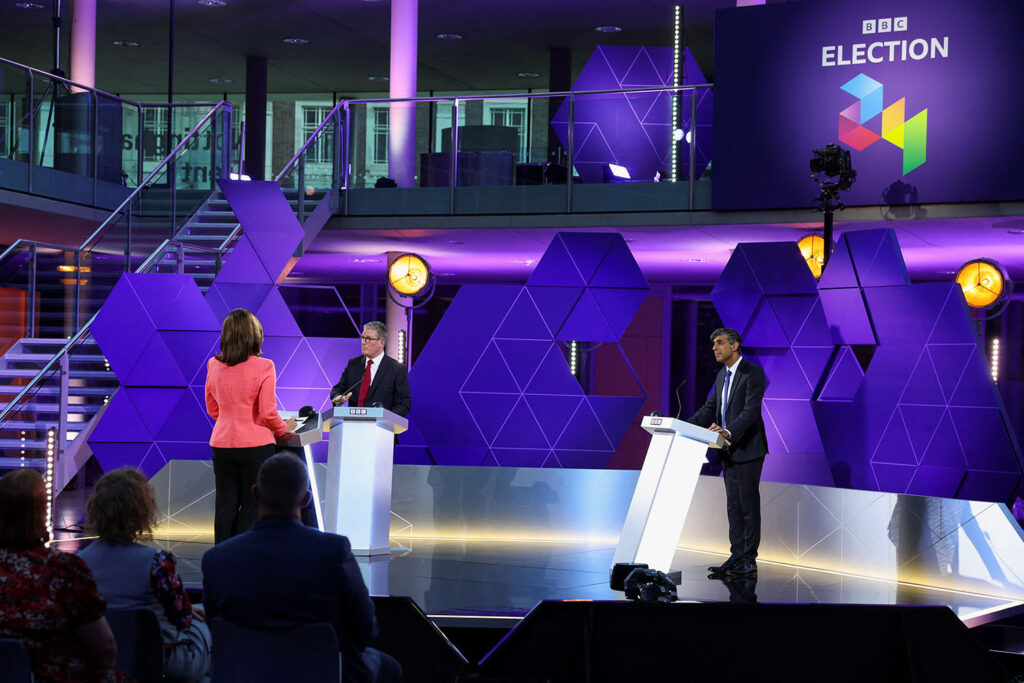

Britons appear tired of Conservative rule. Mismanagement of the pandemic, a sputtering economy with a cost-of-living crisis, and a general unease with the country’s evolution have contributed to the Conservative Party’s deep unpopularity. Sunak’s record has not been able to sway voters, and his performance at the debates and grilling on BBC’s Question Time have not convinced many, either.

The Conservative Party’s ideological ambiguity hasn’t helped. During Tory rule, the party has swung back and forth between center-right mainstream conservatives such as David Cameron, Theresa May, and Rishi Sunak to more populist-tinged firebrands such as Boris Johnson and Liz Truss, leaving voters uncertain of where the party actually stands. The party’s challengers from the populist right, under the charge of Nigel Farage, have picked up on this feeling, further pulling votes away from the Conservatives.

Tory ineptitude has given Labour almost an assured victory. Labour leader Keir Starmer has run a meticulously careful campaign (bringing fresh seriousness to the party following the disastrous electoral showing under the steer of former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn) that several have dubbed as the “Ming vase” strategy. Careful not to lose momentum and potential voters, Labour has taken the approach of staying largely mum about its commitments. Voters may not be particularly enthusiastic about a future Labour government but instead may be more determined to bring about an end to Tory rule.

What are the key issues?

Cost of living

One of the top priorities for voters in this election is the high cost of living across the country. While this varies in priority across voting blocs and age groups, rising energy prices and inflation on everyday goods and services are problems that the next government will not be able to avoid and that will be a decision-making issue for many people who see their paychecks disappearing faster than they used to.

Health

Fixing the National Health Service (NHS) crisis is a critical issue on the ballot as the organization faces some of the lowest levels of public satisfaction in its history. According to YouGov’s latest polling, 84 percent of respondents believe that the government is handling health policy poorly. The mismanagement of the NHS has fueled the British public’s growing frustration with access to medical and social care, with many opting for privatized health. Regardless, Britons still overwhelmingly support the fundamental principles of free healthcare, believing that healthcare should be funded primarily from taxes.

Immigration

While this is an issue that is more energizing for voters and candidates sitting right of center, immigration policies will be key in this election. The most recent government’s deeply controversial Rwanda plan—a proposal that would send asylum seekers who travel from “safe countries” to the UK onward to Rwanda to have their request processed there—will be under scrutiny, as will long waitlists for asylum seekers and recent rule changes for immigrants.

Climate

Hotter summers, stronger storms, and unprepared infrastructure have heightened the urgency to respond to climate change in the UK, with calls for action getting louder in the form of high-profile public protests by organizations such as Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion. While the UK remains committed to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050, there are concerns that the country is falling behind in meeting its targets due to policies implemented by the recent governments. This will be a major issue on the ballot, though not as immediate for voters as their daily expenses.

Budget

A significant question for the next government will be how to reduce national debt to avoid a new round of austerity measures. As it stands, however, proposals from neither the Labour Party nor the Conservative Party clarify how this will be accomplished without either raising taxes or cutting massively on spending to fill a potential £33-billion deficit.

(Not) Brexit

The “get Brexit done” platform that tipped the election in favor of the Tories in 2019 in the last general election seems long forgotten now that 53 percent of surveyed Britons cite the negatives of Brexit far outweigh the positives. Even the Liberal Democrats, considered the “anti-Brexit” party in 2019, are focusing elsewhere, largely running on a social welfare campaign. Brexit is no longer a priority—not even its staunchest opponents are wasting political capital campaigning on the issue despite Brexit’s very real consequences to the UK’s economy and standing.

What do these elections mean for the UK’s foreign policy?

Though this will not be an election driven by foreign-policy issues, the major international concerns in the UK are similar to the concerns in other European countries: Ukraine, the Israel-Hamas war, NATO, and foreign aid funding. The left to center-left groups (the Labour Party, Liberal Democrats, and the Green Party) are also keenly focused on improving relationships with the European Union (EU), compared to the Conservatives, who do not mention the EU at all in their manifestos, and Reform UK, which seeks to remove the UK from the post-Brexit Windsor Framework. NATO commitments are seen all across the board in some form for the major players, though the specifics change—it’s likely that no matter the winner, the UK will continue to push to spend at least 2.5 percent of its gross domestic product on defense. All the major party manifestos call for support for Ukraine. On the Israel-Hamas war and the crisis in Gaza, there appears to be more of an ideological divide among the parties. The Liberal Democrats, the Green Party, and the Labour Party have all called for an immediate cease-fire—albeit Labour has moved comparably slower on this issue. On the other hand, the Conservatives have not called for a permanent cease-fire, preferring to back an “immediate humanitarian pause” instead.

What about relations with the EU?

The Windsor Framework agreement, signed seven years after the Brexit referendum, marked a turning point for the EU-UK relationship. It put in place joint solutions to address the lingering issues from Brexit, including challenges facing Northern Ireland’s access to the UK’s internal market, and signaled a willingness from both parties to move on from tensions spurred by Brexit and negotiations around the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement. While the Conservatives under Sunak initiated the process of reconciliation under the Windsor Framework, the outcome of the UK elections could make way for a deepening and widening of cooperation between the UK and the EU, particularly on security and defense, financial services, and support for Ukraine. A potential Labour government would seek to rebuild ties with Europe, but it’s unclear how far Labour’s proposals may go (such as a politically costly bid to rejoin the EU), fearing criticism from Conservatives and pro-Brexit media.

What about transatlantic relations?

The “special relationship” between the United States and UK is strong but not necessarily privileged. London is no longer the gateway to Europe, and the Biden administration has long prioritized its relationship with the EU. The future of US-UK cooperation is less contingent on who occupies 10 Downing Street and more on who occupies the White House. Ever since 2020, when the UK formally exited the EU, the government has sought a trade agreement with the United States to offset the benefits of unfettered access to the EU’s market. Regardless of the outcome of the US election, it is likely that any future UK government will continue to push for trade negotiations and a deal with the United States. Currently, negotiations around the US-UK free trade agreement have been at a standstill for years, particularly since the United States and UK have diverged on labor standards and agriculture. What’s more, US lawmakers would see little utility in an agreement with the UK that would not (or only marginally) benefit US workers. Regardless, how much the US-UK free trade agreement progresses largely depends on the composition of the US Congress, which will need to greenlight the agreement.

Nicole Lawler is an assistant director at the Europe Center.

Livia Godaert is a nonresident fellow at the Europe Center.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

Further reading

Fri, Apr 28, 2023

How the EU and UK can start to collaborate in a post-Brexit world

New Atlanticist By Jörn Fleck, Ben Judah

As EU ambassadors to London gather to discuss the future of the relationship, here are six ambitious but realistic ideas for cooperation.

Wed, Feb 28, 2024

After 14 years in opposition, what might a Labour foreign policy look like?

New Atlanticist By Francis Shin

UK Shadow Foreign Secretary David Lammy outlined a doctrine of "progressive realism" drawing on the Labour Party's past.

Tue, Mar 12, 2024

Stalled growth in the UK, Germany, and Japan darken global economic outlook

Econographics By Josh Lipsky, Alisha Chhangani

The world's two largest economies won't be able to generate enough growth for the UK, Germany, and Japan—it is going to have to happen from within.

Image: British opposition Labour Party leader Keir Starmer and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak take part in BBC's Prime Ministerial Debate, in Nottingham, Britain, June 26, 2024. Photo via REUTERS/Phil Noble/Pool.