Coronavirus will change the world. The “how” is growing clearer with each day of its global spread.

Unpredictable events produce unforeseen outcomes. Yet sift carefully through the deluge of reporting, and one can discern the first outlines of how this entrepreneurial pathogen will leave its mark.

Here’s just a short list of what we know already as the coronavirus has reached some 94 countries, with more than 100,000 cases and more that 3,400 deaths.

What we’re learning – in real-time, Darwinian fashion – is that proactive countries, societies and individuals are performing far better than reactive ones. Governments that engage in truth-telling are heading off dangers faster than those that obfuscate or delay. (More on that below.)

This week, we were also reminded of the benefits of international collaboration and trust – and the dangers where it doesn’t exist – both in addressing health emergencies and their global financial implications.

For her part, International Monetary Fund Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, pointing to “more dire scenarios,” made available $50 billion to help countries deal with the virus, including $10 billion at zero interest for the poorest of nations.

Get the Inflection Points newsletter

Subscribe to Frederick Kempe’s weekly Inflection Points column, which focuses on the global challenges facing the United States and how to best address them.

Here’s a short (by no means complete) list of what should, or could be, other implications:

The United States and Europe should take this moment as a wake-up call to pay far more attention to addressing non-military national security threats, including their excessive dependence on China for crucial supply chains that reach from pharmaceuticals to “rare earth” materials used in almost all our high-tech gear. Today, about 80% of pharmaceuticals sold in the US are produced in China. China is also the largest and sometimes only global supplier for the active ingredient of some vital medications.

Chinese leaders will have to rapidly adjust their economy to the new reality in which global manufacturers will diversify supply chains, wherever they can, at the cost of Chinese workers. In a country where economic growth figures buy authoritarian leaders their credibility, this year’s slowdown and job losses could have far-reaching consequences.

Chinese leaders are already addressing these challenges through new economic stimulus programs, which are a good thing, but the temptation at the same time has been for more authoritarian controls and nationalist rallying, which is less good, particularly if you live in Hong Kong, Taiwan, or the region.

Iran, one of the four countries hit hardest by coronavirus, with more than 4,700 cases and 124 deaths, is lurching between measures to stop its spread among an increasingly distrustful population and steps it has taken to accelerate its uranium enrichment toward a nuclear weapon.

Iran could choose to rapidly reduce its costly, malign regional behavior, which neither its citizens nor its neighbors can afford. It could pull back from recent steps to increase its uranium enrichment in the direction of weapons grade materials. The alternative, which appears to be the course Iranian leaders have chosen, is an ultimately reckless and perhaps suicidal path of internal repression, ensuring hardline electoral outcomes and external aggression.

Coronavirus has made that path even less sustainable. Watch this space.

This column has tried to keep a healthy distance from U.S. domestic politics. And pathogens are nonpartisan. However, it’s hard not to reach conclusions, looking around the globe, that also reflect on the U.S. coronavirus response.

Countries that delay and dither in their initial responses (China, Italy) pay a heavy up-front price, and those that respond rapidly and responsibly can contain infection rates rapidly (Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong).

Italy and Hong Kong present a powerful comparison. Though Hong Kong shares a border with mainland China, it only this week passed the 100-case mark with two deaths, while Italy has had more than 4,600 cases and almost 200 deaths

Lay aside Italy’s higher population. The more decisive difference was Hong Kong’s proactivity. It closed its schools when Hong Kong had fewer than forty cases and will keep them closed until mid-April, at the earliest. Italy only this week announced a limited closure. Hong Kong also closed most public venues – restaurants, bars, sporting events and theaters. Italy’s response has been spottier, and thus its numbers have grown even as it exported the virus.

If you live in the United States, it’s hard to be reassured by the country’s relatively low number of cases and deaths – 300 and 19. That’s because of the serious lack of testing kit availability until now. Less than 1,600 people have been tested across the country.

A final lesson in this incomplete list is that international leaders must better address our fragile global economy’s ability to absorb shocks like coronavirus, and that should start by addressing our record corporate and sovereign debt levels. Global debt is nearing $244 trillion, the highest level on record.

With most Western central banks near zero interest rates, monetary tools are insufficient to counteract coronavirus – as the Fed demonstrated through the ineffectiveness of its half point cut. Global debt levels restrain the far better alternative of fiscal stimulus.

Lesson here: if kind fate should allow us to slip by this coronavirus without a global pandemic, global recession, or financial meltdown, addressing this debt overhang should be a matter of global urgency.

Perhaps the most important lesson of the past weeks of coronavirus is that the recent rise of authoritarianism globally and the rise of populism and nationalism among Western-style democracies provide a poor recipe for sound, trusted, experienced management of an unfolding global health emergency.

No doubt the coronavirus scare has contributed to the Biden surge of the past week, as American voters in the Democratic party scanned the available choices for steadiness and experience – and other moderate candidates rallied around his flag.

So, the first returns are in regarding how the coronavirus episode might change the world. No doubt the virus is a curse, but it also could be a blessing if politicians and voters heed its lessons.

As Winston Churchill said on the cusp of World War II, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.”

* * *

This article originally appeared on CNBC.com

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @FredKempe.

MUST-READS FROM A WORLD IN TRANSITION

This week’s top reads again focus mostly on the various aspects of coronavirus, which continues to capture global public attention despite a news week that put Senator Joe Biden in Democratic driver’s seat and had Turkish and Russian leaders in Moscow, deliberating the future of Syria’s Idlib.

The pieces include the FT’s look at the danger of debt crisis, two Iranian brothers reflecting on what has gone wrong with their country’s health system, a public health professional’s comparison of coronavirus with the Spanish flue of 1918 and the lesson of effective leadership, and the work of the Atlantic Council’s own Digital Forensic Research Lab in tracking an “infodemic.”

Also don’t miss item #5 and Steve Sestanovich’s smart look in Foreign Affairs at the “deep state” that really makes Russia tick – and thus what Putin’s eventual successor must manage. Our own Anders Aslund reflects on the curiously enduring nature of “Russia’s kleptocratic autocracy.”

#1. THE VIRUS AND ITS ECONOMIC IMPACT

The seeds of the next debt crisis

John Plender / FINANCIAL TIMES

Read every word of John Plender’s “Big Read” on record debt levels in the Financial Times if you want a richer understanding of the most vulnerable part of the coronavirus-hit economy.

The numbers: the ratio of global debt to gross domestic product hit an all-time high of 322% in the third quarter of 2019 and total debt reached some $253 trillion. “The implication,” writes Plender. “If the virus continues to spread is that any fragilities in the financial system have the potential to trigger a new debt crisis.” Read More →

#2. IRAN AND THE VIRUS

How Iran Completely and Utterly Botched its Response to the Coronavirus

Kamiar Alaei and Arash Alaei / THE NEW YORK TIMES

Two Iranian doctors, brothers who were arrested in 2008 in the country, reflect in the New York Times on how a country that has one of the best health care systems in the Middle East has become the poster child for how to get everything wrong in the face of coronavirus.

Nowhere have high officials been as badly affected. Among the more than 3,500 cases are 23 members of parliament, a deputy health minister and several government officials. Among the 107-plus deaths is a senior adviser to the supreme leader.

“Lives could have been saved and the scale of the contagion contained if the Islamic Republic had not made health policy subservient to its politics,” the brothers write. Read More →

#3. PANDEMIC LEADERSHIP LESSONS

What We Can Learn From the 20th Century’s Deadliest Pandemic

Jonathan D. Quick / THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Much separates our times from the days of the Spanish flu of 1918, which took 675,000 lives in the United States, compared by 53,000 in all World War I combat.

On the good side: We have better antibiotics, hospitals, health systems and communication. More problematic: the world’s population is four times larger with more than half in urban areas. Globalization and high-speed travel provide much more opportunity for “community spread.”

But what both periods have in common is how effective leadership can save or cost lives, writes Jonathan D. Quick, author and public health professional. He draws a powerful comparison between Philadelphia of 1918, which muckraker Lincoln Steffens called “the worse governed city in America,” and St. Louis, whose quick, proactive reactions kept its death rates at half those of Philadelphia. It didn’t help that President Woodrow Wilson was so focused on winning World War I that he wouldn’t head pandemic warnings from his Army, Navy, or personal physician. Read More →

#4. WELCOME TO THE INFODEMIC

The Coronavirus and how Political Spin has Worsened Epidemics

Atlantic Council DFR Lab / THE SOURCE

This week, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab in its newsletter featured a round-up of what we’re seeing across the information environment about coronavirus, in our effort to provide a trusted source on what’s right and wrong.

“We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic,” said Tedros Adhonom Ghebreyesus, the director general of the World Health Organization, at the Munich Security Conference last month.

“This is an immediate stress test in the collective effort including government, media and private industry to build resilience against active disinformation and passive misinformation,” our DFRL lab wrote. “Human lives hang in the balance.” Read More →

#5. PUTIN’S SUCCESSOR

The Day After Putin

Stephen Sestanovich / FOREIGN AFFAIRS

We Need a Small War

Anders Aslund / BERLIN POLICY JOURNAL

Steve Sestanovich’s must-read on Russia in Foreign Affairs suggests that experts have been asking the wrong questions about the country and Putin – “on his personality, his wealth, his approval ratings.”

Instead, he suggests studying “his true legacy.” In Sestanovich’s view, that is the re-empowering of the state bureaucracy and, in particular, the national security establishment, “the hydra-headed complex of military intelligence, and law enforcement ministries.”

He convincingly argues these institutions “may well determine not only who becomes the next president of Russia but what Russian politics will look like after Putin.” Read More →

Also don’t miss the Atlantic Council’s Anders Aslund in Berlin Policy Journal. Anders is one of the keenest minds on Russia’s economic structure as “an authoritarian kleptocracy.” He analyzes why this “classic decline power” resists reform, ignores growth, neglects its population – and survives. Read More →

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

ATLANTIC COUNCIL TOP READS

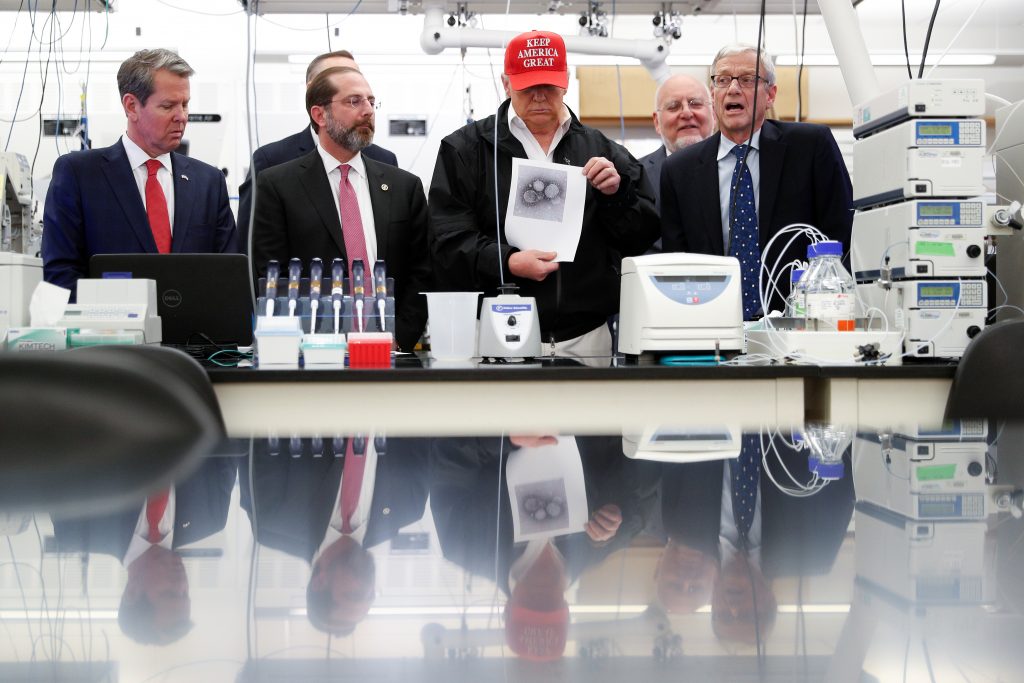

Image: U.S. President Donald Trump displays a photo of the COVID-19 Coronavirus beside Georgia Governor Brian Kemp. HHS Secretary Alex Azar and C.D.C. Associate Director for Laboratory Science and Safety Steve Monroe at the during a tour of the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S., March 6, 2020. REUTERS/Tom Brenner