India’s external affairs minister, representing the world’s largest democracy and second-most-populous country, shared with me a concept that he believes captures the geopolitical moment.

Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, one of the keenest international thinkers of our uncertain times, reckons that the United States, after years of unrivaled global leadership, is in a state of “strategic contraction.” He sees this as one of four factors shaping our times.

The other three: China’s increased relevance in almost every corner of the world; the rise of middle-sized powers with regional and international influence (India being atop that list); and the evolution of what Jaishankar refers to as ad hoc, interest-based “shareholder groups.” The latter won’t replace formal treaty alliances, he argues, but will operate alongside them.

As an example, he cites the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (known as “the Quad”) of the United States, India, Japan, and Australia—which was born in 2007 and, after a brief pause, was reestablished in 2017 but has gained greater relevance recently. In addition, he mentions a “new quad” announced in October that includes the United States, India, Israel, and the United Arab Emirates.

Jaishankar doesn’t introduce the notion of US “strategic contraction” as a theoretical matter, but rather sees it as a reality that’s been unfolding ever since the Obama administration’s “leading from behind,” through the Trump administration’s “America First,” and right into the Biden administration’s “Build Back Better” mantra, with its emphasis on rebuilding at home.

By his calculus, the United States “will still be the premier power by a large margin but one more realistic and open to working with others. We are seeing that, especially under Biden. The contraction actually helps create a transitional order” from the Cold War period of US-Soviet competition through the post-Cold War years of US dominance to the period ahead.

Like all periods of change, however, this transition comes with risks as China tests its new muscle, Russia maneuvers to regain lost ground, and the United States comes to terms with a messy, contested world.

Since speaking with the Indian minister in Dubai, I’ve been sharing his thoughts about US “strategic contraction” with European and Middle Eastern experts and officials. The term resonates with them.

Our partners are still reeling from the unconditional US troop withdrawal from Afghanistan that allowed the return to power of the Taliban, against whom they had helped fight. They now look around and see Russia’s military buildup near Ukraine, a migrant crisis on the Belarus border, and growing Chinese military pressure on Taiwan. They harbor rising doubts about how Washington will navigate these challenges, knowing they are unready to do so alone.

Yet those who argue the United States is withdrawing from the world stage couldn’t have it more wrong. Washington will remain a leading voice on key issues from climate change to nuclear proliferation. In a world that constantly demands our attention and engagement, US isolationism isn’t an option.

US allies have noticed—and they’re concerned

What our partners see now is a less externally confident, more internally focused United States guided by a sober calculation of its leverage and resources, burdened by public weariness with the cost of international leadership and hobbled by domestic political polarization.

They agree with the Biden administration’s conviction that it must strengthen itself at home to effectively lead abroad. In that spirit, they welcome the new $1.2 trillion infrastructure law and are closely watching the roughly $2 trillion social-spending and climate bill, passed Friday by the House and now heading to the Senate.

That said, the United States’ closest friends and allies are most concerned by the uncertain direction of US democracy, with former US President Donald Trump still denying the legitimacy of his defeat and the Biden administration struggling to summon broad public support.

In my travels through Europe and the Middle East over the past month, I was most struck by how many conversations began with questions about the health and direction of the United States’ democracy. The topic seems of greater concern to our partners than the rise of China’s authoritarian state.

It isn’t new that the world follows US domestic politics closely. What seems different is the bewildered tone of our allies in asking whether Americans understand the dangers of any erosion in democracy and are willing to address them. I was surprised how often my foreign friends quoted from Robert Kagan’s recent foreboding piece in the Washington Post, “Our constitutional crisis is already here.”

Lessons from US “strategic contraction” in Afghanistan

What seems to have shaken our partners most profoundly was the nature and speed of the United States’ unconditional withdrawal from Afghanistan, without serious consultation with allies who had troops there or with Mideast partners who fear the emergence of an extremist-run country and the reemergence of a terrorist safe haven.

“It said nothing good about the steadiness, reliability, or predictability of US leadership,” one Middle Eastern official told me. “Even the Taliban was surprised by how quickly it all unfolded.”

The picture that presents is of an emerging world order shaped by greater multipolarity and regionalism. It’s less likely to break down into clear camps split between China and the United States. Too many of the United States’ most important allies have China as their biggest trading partner and will resist being drawn into any global either-or contest.

US partners will look to new regional arrangements, involving the United States where possible, and they will promote their trading and security interests in a pragmatic way, participating if invited into larger US schemes like the Biden administration’s upcoming democracy summit or “Build Back Better World” approach laid out at the Group of Seven summit in June as a sort of answer to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

At the same time, US partners and allies will hedge their bets, more certain about China’s course—even though they may not like it—than they are about the US trajectory.

Many of our partners hope the United States once again will play the galvanizing role that was decisive during World War II, did so much to define the post-war period’s world and institutions, and determined the Cold War’s outcome.

For now, however, US partners feel they need to navigate the reality they see in front of them: US “strategic contraction.”

This article originally appeared on CNBC.com

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @FredKempe.

THE WEEK’S TOP READS

#1 The Bad Guys Are Winning

Anne Applebaum | THE ATLANTIC

Writing for the Atlantic, Anne Applebaum offers a must-read on the future of democracy by providing a compelling look at the reality of today’s autocracies and their common cause.

“Nowadays, autocracies are run not by one bad guy, but by sophisticated networks composed of kleptocratic financial structures, security services (military, police, paramilitary groups, surveillance), and professional propagandists,” she writes. “The members of these networks are connected not only within a given country, but among many countries.”

The benefits to autocrats are significant “because Autocracy Inc. grants its members not only money and security, but also something less tangible and yet just as important: impunity.”

Applebaum concludes, “If America removes the promotion of democracy from its foreign policy, if America ceases to interest itself in the fate of other democracies and democratic movements, then autocracies will quickly take our place as sources of influence, funding, and ideas… They will continue to steal, blackmail, torture, and intimidate, inside their countries—and inside ours.” Read more →

#2 ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ Makes China a Tougher Adversary

Kevin Rudd | WALL STREET JOURNAL

In case you missed it, former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd dissects a move by the Chinese Communist Party, at its annual plenum, to elevate “Xi Jinping thought” in a manner that has only happened twice before in party’s one-hundred-year history.

From this point forward, “to criticize Mr. Xi is to attack the party and even China itself,” writes Rudd, who is also a member of the Atlantic Council’s International Advisory Board. “Mr. Xi has rendered himself politically untouchable.”

Rudd’s bottom line for the Biden administration is worth reading: Xi is “on track to rule China through at least five American presidencies. Which is why the US needs urgently to establish a long-term, bipartisan national China strategy through to 2035 and beyond.” Read more →

#3 On Putin’s Strategic Chessboard, a Series of Destabilizing Moves

Anton Troianovski | NEW YORK TIMES

The New York Times’ Anton Troianovski makes sense of the Russian troop buildup near Ukraine, the migration crisis in Belarus, and escalating fears over Russian natural-gas deliveries ahead of a cold European winter.

Putin has “put his cards on the table,” he writes. “He is willing to take ever-greater risks to force the West to listen to Russian demands. And America and its allies are sensing an unusually volatile moment, one in which Mr. Putin is playing a role in multiple destabilizing crises at once.” Read more →

#4 ‘This experience broke a lot of people’: Inside State amid the Afghanistan withdrawal

Natasha Korecki and Nahal Toosi | POLITICO

Politico delivers a heart-breaking narrative from inside the US State Department as employees there scrambled to respond to the urgent pleas of Afghans and Americans trying to escape the country during the US troop withdrawal.

Interviews and administration emails that Politico obtained through the Freedom of Information Act “reveal the desperation and disorganization that consumed” State Department employees “as they feverishly attempted to assist Afghans and Americans” that were stranded in the country.

As the Politico reporters write, “their stories are a testament to the US government’s lack of preparedness for the cratering security situation, even as President Joe Biden pushed through his decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan by Aug. 31.” Read more →

#5 Can Russia’s Press Ever Be Free?

Masha Gessen | NEW YORKER

This week’s must-read is Masha Gessen’s long-form profile in the New Yorker of Dmitry Muratov, the editor of Novaya Gazeta and this year’s Nobel Peace Prize winner alongside Maria Ressa, another campaigning journalist in the Philippines.

“Imagine,” Gessen writes of the curious structure of the Novaya Gazeta, “the Village Voice of the nineteen-eighties crossed with a mutual-aid society, but run, at times, like Occupy Wall Street. Novaya Gazeta is a community and a humanitarian institution, and it is very messy.”

The secret to its survival is Muratov’s careful balancing act and personal relationships with many of the country’s most powerful individuals. “Muratov pushes the ever-shifting boundary of what is possible in Russia, but never so far that Novaya Gazeta is shut down,” Gessen writes, recounting how angry Muratov gets when asked how he has secured the paper’s survival for so long.

“Do we have to be shut down to become trustworthy?” he bellowed at Gessen. Read more →

Atlantic Council top reads

This article was updated on November 22, 2021.

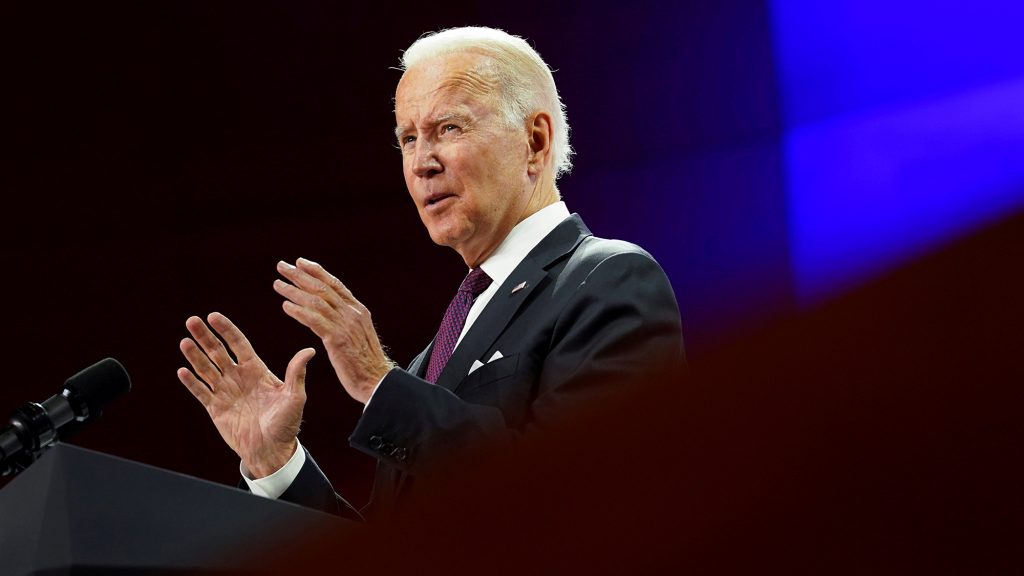

Image: US President Joe Biden speaks during a press conference during the G20 leaders' summit in Rome, Italy on October 31, 2021. Photo via REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque.