The 5×5—Addressing the global market for offensive cyber capabilities

The proliferation of offensive cyber capabilities (OCC) has significant geopolitical implications. States leverage their cybersecurity industries to bolster their national security, build their economies, and engage in diplomacy. Several recent rapprochements, such as that of Israel and some of the Gulf states, can be chalked up in part to exchanges of OCC. The scope of OCC and its supporting industries varies between some analysts but the capabilities are employed across the world to everything from technical training to vulnerability development to surveillance tools and weapons of war.

Unfortunately, the same tools and skills that are useful for countering terrorism and criminal activity can be used to spy on journalists, significant others, or business rivals. In November 2021, the US Commerce Department added four OCC companies to its Entity List, effectively banning US organizations from selling technology to the companies for their engagement in “activities that are contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States.” In April 2022, the European Union launched an inquiry committee to investigate on of the companies, NSO Group, and its widely covered Pegasus spyware.

We brought together a group of experts to unpack the OCC market and discuss the implications associated with the proliferation of hacking tools.

#1 How do you define offensive cyber capabilities (OCC)? What does and does not fall within the purview of the term?

Luca Allodi, assistant professor, Security Group of the Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e):

“OCC is a mix of technical, operational, and tactical capabilities that an actor or group of actors possess to perpetrate a cyberattack. These capabilities can either be produced in-house or be (at least partially) obtained from third party suppliers acting either in the public space (e.g., Hacking Team, NSO, etc.), or as part of the cybercrime economy.”

Winnona DeSombre, fellow, Cyber Statecraft Initiative:

“Offensive cyber capabilities are all the components that make up an offensive cyber operation. Everything from vulnerability research and exploits, malware, and technical command-and-control infrastructure, all the way to employee training and operational/process management.”

Sandro Gaycken, founder, Monarch Ltd., A Private Intelligence Company:

“OCC are capabilities to infiltrate foreign information technology (IT) systems to exfiltrate information or to conduct sabotage or targeted manipulations. A variety of tactical sub-aims can be added to that, but this is largely it. Penetration testing or responsible disclosure do not fall under the term as both are usually far away from actual OCC requirements and techniques.”

Kirsten Hazelrig, policy lead, The MITRE Corporation:

“This question is often answered with a very tactical response of gaining access to or degrading systems, and even the term ‘OCC’ locks many into a mindset of nation-state adversaries carrying out militaristic campaigns for some strategic goal. However, the proliferation of these capabilities has expanded us far beyond that narrow use case. The digital environment overlays every aspect of modern life, and OCC are any that manipulate and harvest that environment, from surveillance to kinetic effect.”

JD Work, senior fellow, Cyber Statecraft Initiative; professor, National Defense University – College of Information and Cyberspace; and research scholar, Columbia University – Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies:

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any agency of the US government or other organization.

“To paraphrase a famous saying, the only definition that is worth anything is what the adversary uses. We have had decades of debate over how we describe offensive action, and the capabilities that enable these options. It does little good to revisit debates over distinctions of nomenclature in tooling, and the weaponized forms of this tooling used for access and attack. These portfolios must be evaluated in context, and it is where and how such context is situated that bounds the problem space of concern here.”

#2 What are the implications of the existence of an OCC marketplace on international conflict and cooperation?

Allodi: “It generates a new class of threat actors that may not be competent (or resourceful) enough to generate and operationalize the attack(s) themselves. This also “levels down” the variance in offensive capabilities put in place, as more and more sophisticated and expensive attacks *a-lá* Stuxnet disappear, and more attacks using common malware or shared exploitation infrastructure emerge.”

DeSombre: “Having an international OCC marketplace takes capabilities that are incredibly hard for a government to develop in house, and turns them into something that a government can buy really easily—a “pay-to-play” model where governments with enough money can create offensive cyber programs far more easily than before.”

Gaycken: “The OCC marketplace is largely oriented along the broad geopolitical lines we see anyhow. Some groups deliver into China and Russia, some deliver into Middle Eastern and North African autocratic systems, some deliver only to NATO or NATO-friendly countries. However, the marketplace is unstable and unreliable. Contrary to common belief, nations are not hoarding vulnerabilities. On the contrary. Selling exploits is still difficult and frustrating, which in turn leads to violations and fluctuation of talent and loyalties.”

Hazelrig: “The commercial availability, and resultant commoditization and accessibility of OCC have fundamentally changed the discussion analogously to enabling nuclear capabilities for every warlord, despot, and cartel. The cost of entry has been lowered to be the point that that any of these capabilities that were once reserved for nation-states can be contracted.”

Work: “The marketplace for offensive cyber capabilities has existed since the evolution of the cyber domain as a contested battlespace. The question here therefore is both retrospective, regarding the factors arising out of this market that have reshaped international interactions to date, as well as forward looking, towards the future outlook of that market. In hindsight, one realizes that these markets have redistributed the generation of intelligence and strategic power in the new domain across a number of actors, and in a variety of organizational and transactional forms, that has not been well understood to date in most policy and scholarly debates. Looking at how those markets are developing, it is that continuing misunderstanding that is creating the greatest risks, as poorly fitted policies shaped by industrial era, defense industrial base-centric thinking seek to constrain proliferation dynamics driven by the radically different characteristics that are presented across networked innovation economies.”

#3 What are the greatest challenges to imposing controls on OCC compared to other technologies?

Allodi: “I am not an export-import control expert, but I can imagine that monitoring and enforcement are especially difficult. The stealth and “by-proxy” nature of attacks generated by means of acquired OCC (e.g., Access-as-a-Service) create both a difficult setup to detect (especially in a timely fashion), and allow perpetrators to remain relatively disconnected from the attack operation by employing, in essence, somebody else’s attack infrastructure.”

DeSombre: “First off, some of the things that I define as OCC are hard to regulate as tools: export control is a method commonly used for this, but is not enough. Second, talent development (another OCC category) relies on people, and we want to walk a line between talent development and talent restriction. US President Joe Biden just signed a law prohibiting some US intelligence officials from selling their services to other countries for thirty months after retiring, but this could be difficult to enforce if they are not directly working for another country.”

Gaycken: “Clueless regulators and think tankers are the greatest problem in imposing controls on OCC. The problem is not as it is portrayed. There is a lot of loyal and highly gifted talent requiring good incentives and simple procurement from the right buyers, not more control. More control will only lead to companies relocating and their OCC being sold to where there is less control—and that will be our autocratic enemies. This cannot be desirable.”

Hazelrig: “The pervasive and transcendent nature of cyber creates unique challenges of scope and jurisdiction in responding to OCC. Unlike the traditional arms trade, effective cyber tools and technologies are fleeting, often leaving regulators to reactively control the global application of knowledge and innovation. At the same time, they must be mindful that this same ecosystem is intertwined with and interdependent on legitimate uses such as cybersecurity research, law enforcement, and security.

Work: “Traditional nonproliferation measures to craft international controls, and counterproliferation missions for interdiction, are generally concerned with a very narrow set of technologies used in very specific processes for a rather rarified set of purposes. The specialized, applied knowledge involved in building, refining, iterating, and bringing into production the weaponized forms of those purposes arises within very unique environments. Offensive cyber capabilities, in contrast, are built upon the pervasive vulnerabilities at the heart of our contemporary systems and networks. That the density of these latent and constantly shifting exploitation opportunities is not limited to narrow, arcane contexts but rather is most acutely of concern in the technologies that underpin our daily lives—from personal devices to enterprise functions to the industrial control systems upon which modern civilization depends. Each one of these contexts can give rise to potential insight that may be leveraged by offensively minded actors.”

More from the Cyber Statecraft Initiative:

#4 What lessons from other counterproliferation efforts can be applied to curbing the proliferation of OCC?

DeSombre: “I am hesitant to transplant other counterproliferation regimes onto cyber (given how incessantly cyber is compared to the nuclear domain), and I am not a counterproliferation expert in other domains. However, I will say that in some ways, counterproliferation efforts in the commercial cyber space mimic those of more traditional arms sales. Naming and shaming a company seems to trigger a rebranding of the company, rather than changes in behavior.”

Gaycken: “This entire question is academic nonsense. There is not “too much” proliferation of OCC, there is too little of it. Israeli NSO-style products are not really OCC, but LI [lawful interception]—and would have been sufficiently regulated. They just leaked into different contexts.”

Hazelrig: “Many counterproliferation strategies (e.g., arms, drugs) work to regulate sales and distribution of the target. However, cyber capabilities require that we consider the entire use case and business operational chain in order to directly dissuade and impede the irresponsible proliferation of OCC. Costs should be increased through countering and enforcement efforts to thwart illegal and abusive use, using law enforcement, diplomatic, and regulatory levers.”

Work: “The most dangerous proliferation networks are those that have longevity, and have mastered the problems of scale—especially across multiple differing customer contexts. The more established proliferants and their enablers become, the more likely they are to have found working solutions for problems of customer and supplier discovery, counterparty trust, movement of funds, and other transactional frictions. Long-standing relationships are harder to subvert, which makes penetration of these networks more difficult for intelligence services and law enforcement agencies that would seek to understand and disrupt these enterprises. And networks that have proven able to do business in multiple settings under differing business models are also those that are most likely to have fallback options to recover from disruption attempts. Thus, one of the key lessons to take away for cyber counterproliferation is to ensure that adversaries are not allowed to persist to reach those longevity thresholds.”

#5 How much power can the United States and its allies have on shaping the future of the OCC industry? If they squeeze the industry, won’t it go elsewhere?

Allodi: “I think that, if overly-regulated, most likely these capabilities will remain available in (possibly dedicated) underground marketplaces. The self-regulated underground market is maturing; emerging marketplaces already support trade of increasingly more advanced offensive capabilities in the absence of a central regulator. Threat actors operating in this space may also represent a “pool” of resources available to the nation-states under which jurisdiction they operate, while tolerated. Russia is an example of this.”

DeSombre: “There is a lot of power that the United States and its allies have on the future of OCC. But only if they use both sticks and carrots—squeezing alone will not do any good. For one, the United States and its allies still purchase a decent number of these capabilities, for legitimate cybersecurity reasons (think bug bounties, penetration testing, etc.). Having more due diligence on the companies with which they work or are headquartered in their country, while also enticing researchers to work for those firms, would be a powerful combination of policies.”

Gaycken: “They should work with the OCC community in a way that is fair and meets actual technological development cycles, and they will benefit greatly from it. If they squeeze it, it will just go to countries who appreciate this kind of talent, and there will be an ever-fast erosion in offensive cyber capabilities from democratic nations to authoritarian ones. This is already the case, anyhow.”

Hazelrig: “As many of these capabilities exploit the infrastructure and products of US corporations, the US government has unique opportunity and moral responsibility to not only enable domestic law enforcement action, but also the imposition of cost through countering strategies, civil litigation, and private right of action. The industry is global, and those that wish to evade controls are already doing so locating the company, the operation of subsidiaries, or proxies in more lenient jurisdictions. This emphasizes the need for a broad response that goes beyond industry regulation or export control.”

Work: “Like most forms of soft power, the US government and its allies may wield the weaponized entanglement of interlocking financial, technology, and social environments to great effect should they choose to do so. But the unintended consequences here present wicked problems, and can blowback in often unexpected ways when using the blunt instruments developed to constrain earlier capabilities. It is always tempting, from the legal and policy perspective, to adapt existing mechanisms to new problems. However, this has had very limited success in the past decade in imposing cost on adversary behaviors—and almost certainly added substantial friction to many things underpinning Western capabilities innovation, in ways that were not understood at the time and are still poorly considered even now.

The most problematic actors responsible for offensive cyber capabilities development and proliferation are already “elsewhere.” There remains a substantial fallacy in the policy community that seeks to characterize exploit portfolio discovery as a uniquely American “original sin.” But this ignores the complex history of the past several decades of parallel development, unconventional innovation, and independent agency of the global hacker scene—and the state programs that were built on the foundation of that technical expertise. The complexity of real markets, especially those that enable threats from hard targets and in denied areas, does not make for the kind of breezy and fact-challenged books that get popular traction in the Beltway. We must face the realities of those problems now, and ensure that our policies are appropriately crafted to deal with that present danger not only as some theoretic reaction to foreclosed pathways in the simplified narratives that have shaped conventional consensus.”

Simon Handler is a fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. He is also the editor-in-chief of The 5×5, a series on trends and themes in cyber policy. Follow him on Twitter @SimonPHandler.

The Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative, under the Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology.

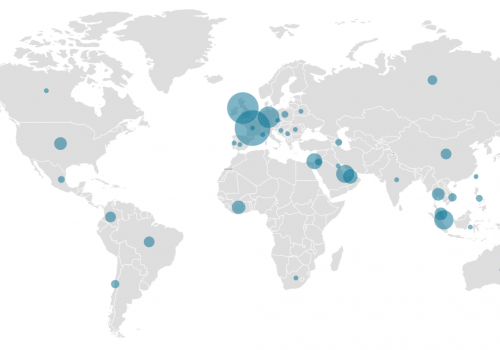

Image: Tracking by Ifrah Yousuf, CyberVisuals