2025 Post-Covid Scenarios: Latin America and the Caribbean

The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) has found that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to the worst economic decline in Latin America and the Caribbean in two hundred years. In addition to its economic toll, the pandemic has had a devastating impact on the region’s society and health systems. Although the region represents just 8 percent of the global population, it has reported 28 percent of all deaths.

The Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center and Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security look ahead to 2025 in LAC 2025: Future Scenarios, a new report produced with the help of the IDB. Co-authored by Peter Engelke and Pepe Zhang with Sara Van Velkinburgh, the report builds upon the scenario work conducted by the IDB and NormannPartners to identify the key factors shaping the region’s post-COVID-19 outlook: health outcomes, societal agency, and Latin America and the Caribbean in the global landscape. Based on these factors, the report offers three plausible 2025 scenarios for the region: COVID’s Lasting Toll, Regionalisms on the Rise, and The Great Divide.

Three 2025 Post-COVID Scenarios: COVID’s Lasting Toll, Regionalisms on the Rise, and The Great Divide

Executive Summary

With vaccine rollouts underway, the world finally has an opportunity to look beyond COVID-19 and to plan meaningfully into the future. Nevertheless, uncertainties abound, and new shocks may continue to arise, potentially bringing about social, economic, health, political and other consequences. As a region, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is vulnerable to these uncertainties and shocks, due to preexisting weaknesses such as underinvestment in public health and healthcare, inequality, high labor informality, low productivity, and weak democratic governance. Indeed, these structural weaknesses made LAC among the worst coronavirus-affected regions in human and socioeconomic terms.

Going forward, the region’s leaders must address the risks and opportunities that will shape the post-COVID future. Which key uncertainties will drive the region forward in the coming years, for better or worse? What are the major opportunities and risks facing governments, the private sector, and citizens, and to what extent can they effectively anticipate and navigate them?

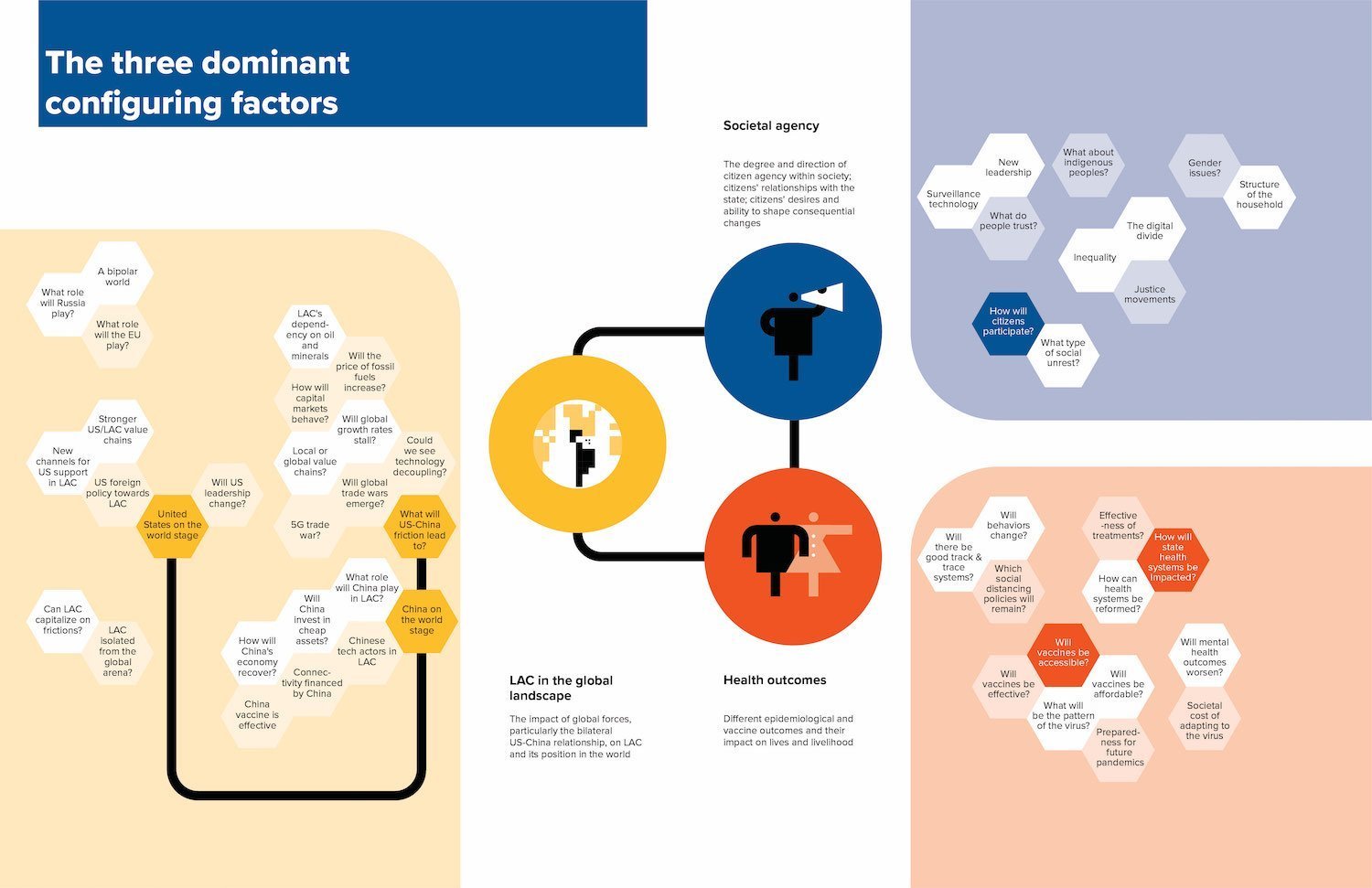

This report provides an outside-the-box framework to help unpack these questions and to challenge static assumptions about today’s rapidly changing world. Building upon a robust scenario-planning exercise involving eighty-plus experts, the report identifies three main drivers of change—labeled as the dominant configuring factors (DCFs)—that will shape the region’s post-COVID-19 future:

- Health Outcomes: Different epidemiological and vaccine outcomes and their impact on lives and livelihoods, e.g., herd immunity through widespread vaccination versus viral mutations rendering vaccines ineffective; and structural deficits in public health access and administration;

- Societal Agency: The degree and direction of citizen agency within society; citizens’ relationships with the state; citizens’ desires and ability to shape consequential changes, e.g., an active and engaging civil society versus a subdued and disinterested one;

- LAC in the Global Landscape: The impact of global forces, particularly the bilateral US-China relationship, on LAC and its position in the world, e.g., LAC countries feeling “forced” to choose sides between the United States and China versus maintaining relative neutrality and autonomy; or stronger integration with the United States as the Biden administration doubles down on engagement with hemispheric partners.

The evolution and interplay of these three DCFs could play out in many different ways. This report highlights three plausible future scenarios assessing how LAC’s post-COVID future could unfold out to 2025. These three alternative scenarios and their underlying analytical process aim to provide readers with useful and contrasting vantage points to reflect on the pathways available to shape the future. The hope is that the scenarios will inform LAC’s policy makers and other relevant stakeholders and help guide their decision-making (see checklist for policymakers in Appendix 2). The three scenarios are:

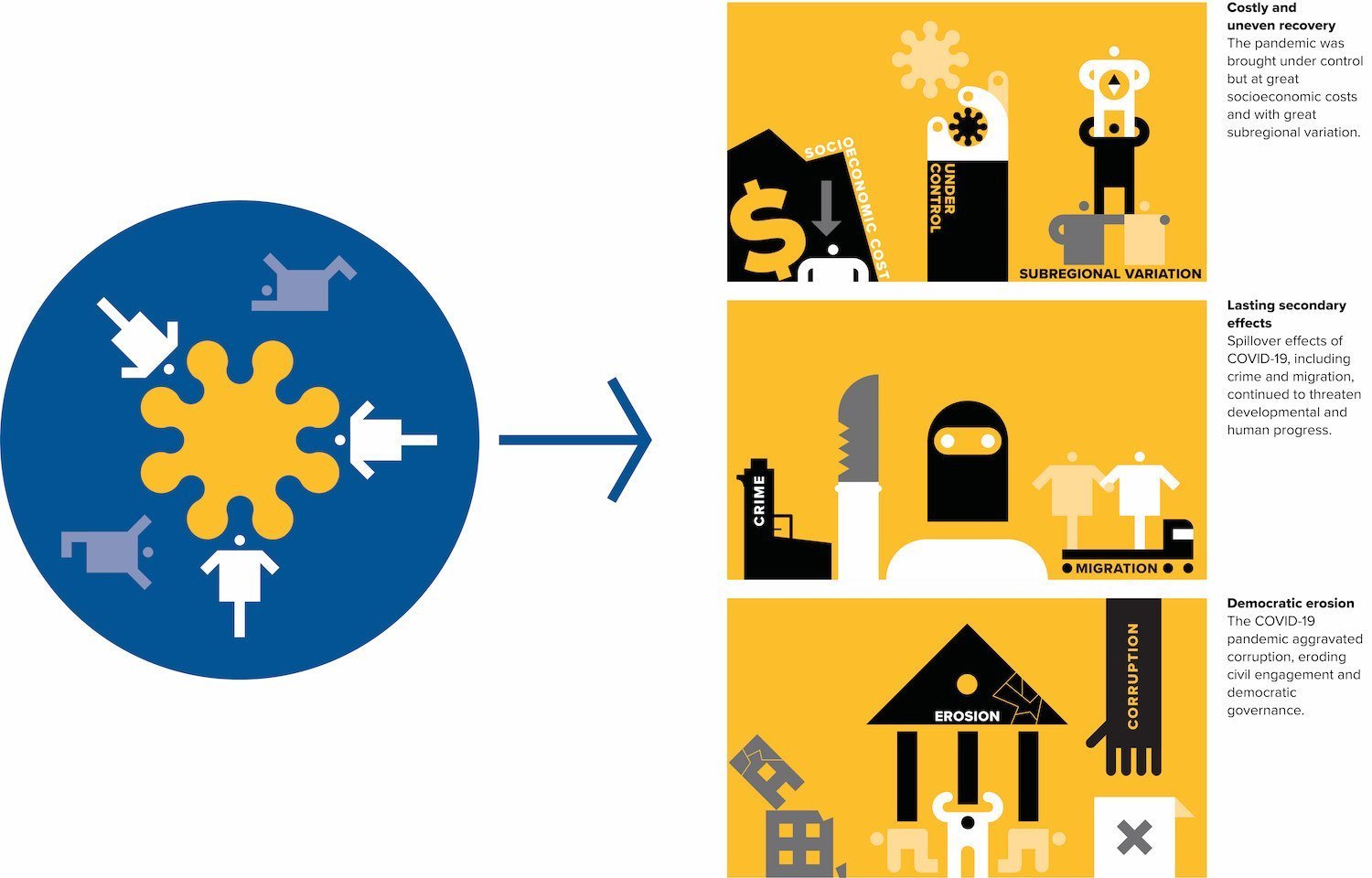

- Scenario A: COVID’s Lasting Toll. Widespread vaccination eventually ended the pandemic, allowing the region to recover by 2025. However, COVID-19 had taken a considerable toll in terms of public and economic health, with lasting consequences. Democratic governance and government capacity eroded in some parts of the region because of growing violence and crime. Societal activism became increasingly frustrated by governments employing pandemic-justified surveillance and digital technologies, and civil society became discouraged by various less-than-successful mobilizations. Internationally, competitive dynamics drove both the United States and China to actively engage the region through 2025, although most countries remained neutral and refused

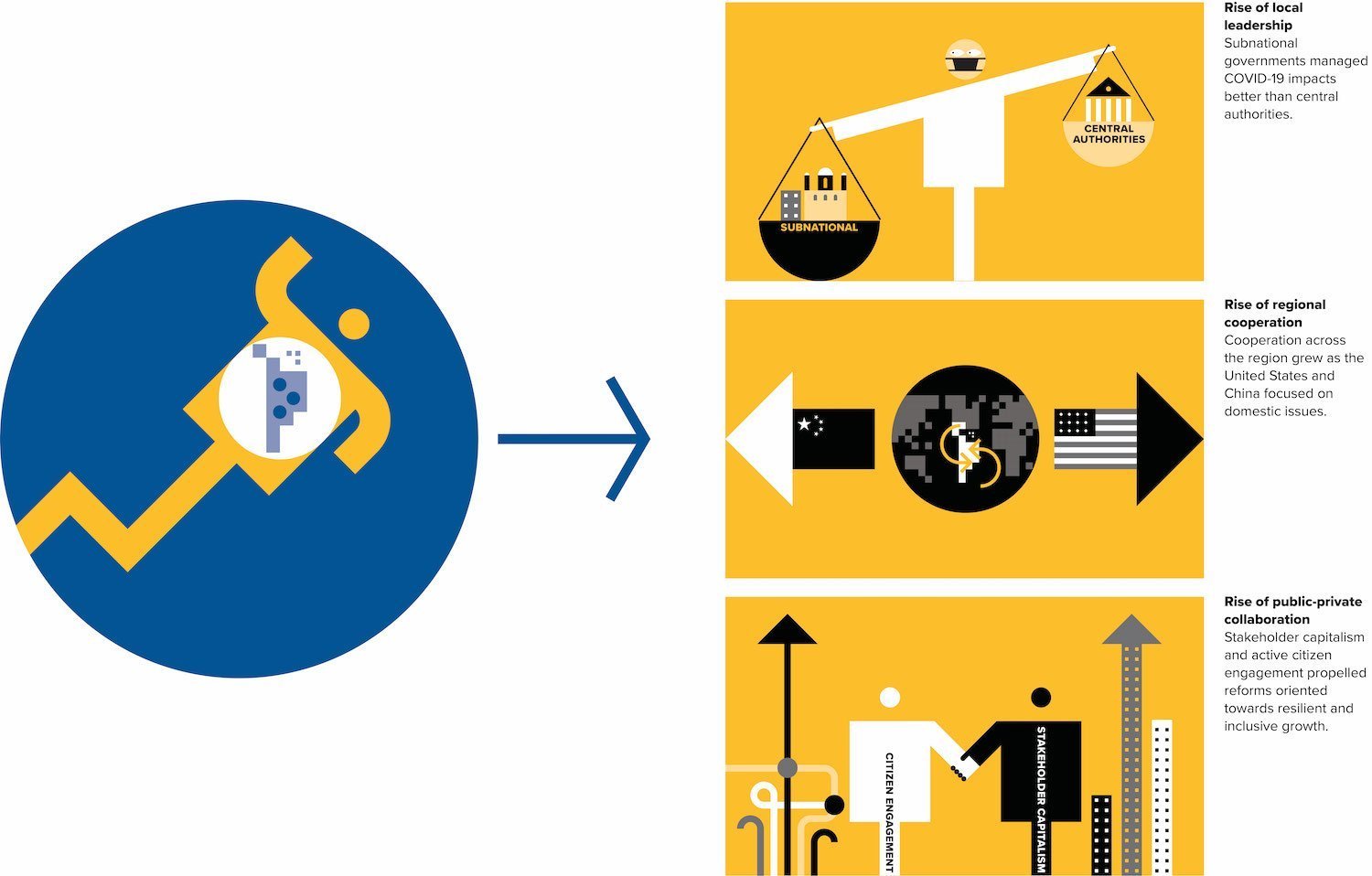

- Scenario B: Regionalisms on the Rise. Two types of LAC regionalism emerged. Internationally distracted and domestically focused, China and the United States engaged in a kind of benevolent neglect, in which LAC regionalism—growing collaboration and integration among LAC countries—flourished. At the national level, as central governments struggled with the pandemic response, more agile local authorities had more success in coping with COVID-19 management and recovery. This provided the impetus for another form of regionalism—in a subnational context—characterized by the rise of city/state leadership within the region, and cooperation among these subnational actors across national boundaries. In parallel, innovative solutions and partnerships from/with business leaders and societal representatives—initially born out of necessity due to fiscal frugality—yielded positive results and invited emulation across the region. This led to a more engaged civil society and a private sector that doubled down on “stakeholder capitalism,” paving the way for a green recovery, especially in climate-affected areas.

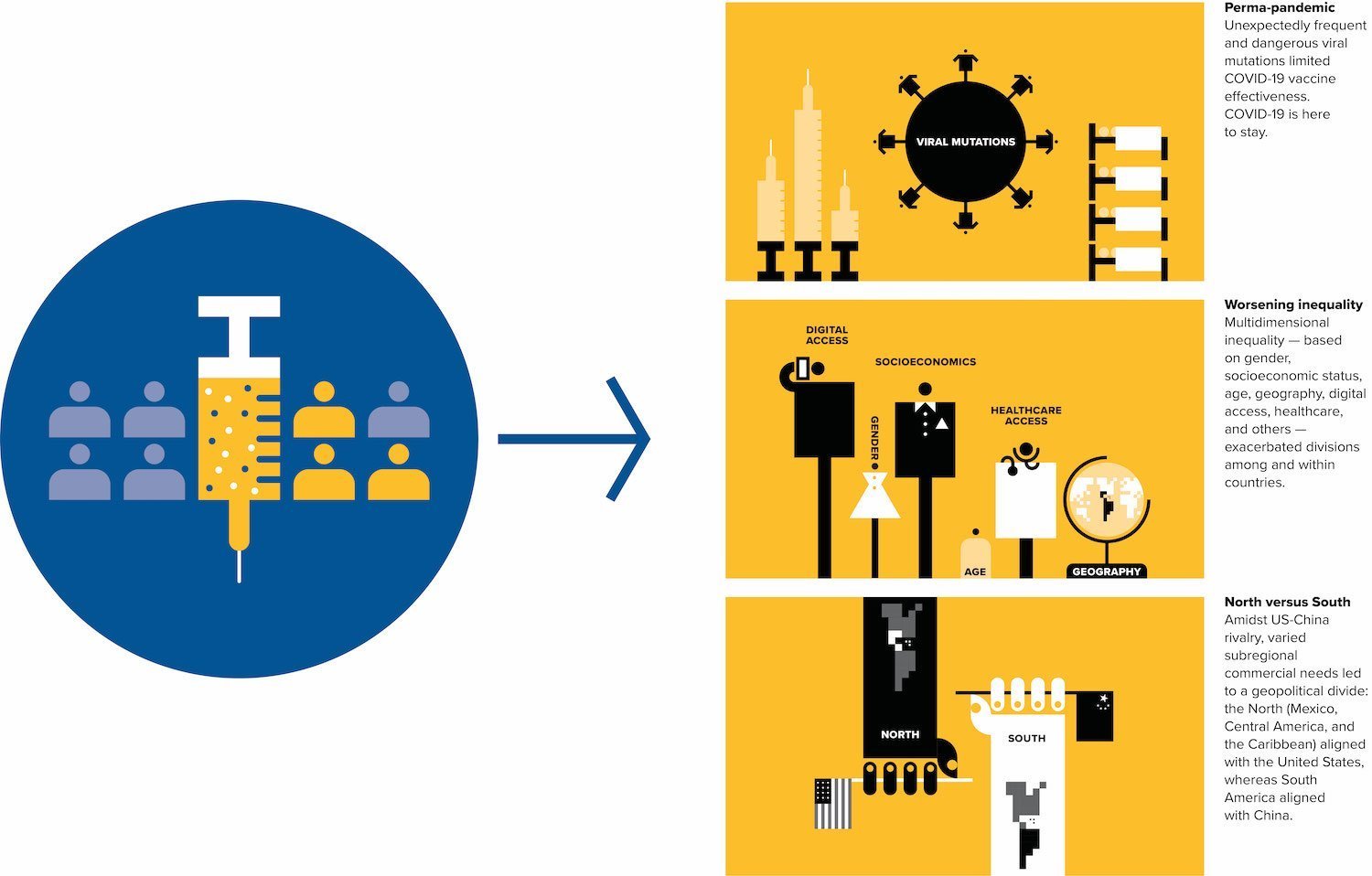

- Scenario C: The Great Divide. As continuous viral mutations dashed hopes of long-lasting herd immunity, COVID-19 morphed into a rolling pandemic that weighed differently on populations and countries across the region, often causing divergent outcomes. LAC’s preexisting multidimensional inequalities—by gender, socioeconomic status, age, geography, race and ethnicity, digital access, and others—were amplified by COVID-19. Access to effective vaccines and treatments (while temporary) became itself a new form of inequality, favoring commercial and political elites and causing further societal polarization. Domestic and regional economic recovery remained elusive and uneven. Internationally, a North-South divide took hold within LAC on the back of varied commercial and political needs: Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean came to align and integrate more closely with the United States, whereas much of South America developed stronger and complementary ties with China.

I. Preface

Although the world and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) remain under the pandemic’s grip, some countries should begin to emerge stronger than others during 2021-2022. Amid continued uncertainties ranging from health to the economy, each country’s success over the next few years will depend on its ability to anticipate, navigate, respond, and rapidly adapt to a changing context. Government policies, business decisions, and citizen activity all will shape society in the coming years. The region will need sound policy making, private sector dynamism, and citizen engagement to jump-start a more sustainable and inclusive recovery.

Policy makers, the private sector, and other actors face an opportunity to address this crisis from a strategic, long-term perspective. This report is intended to help stakeholders assess several major sources of uncertainty that will shape LAC’s post-COVID future through 2025. Given these uncertainties, this report presents some plausible scenarios that might unfold over the next four years, and provides a framework for (re)thinking LAC’s future using these scenarios and their underlying drivers of change. The scenarios are neither forecasts nor the “most likely” futures; they are not the “best” or “worst” futures, but alternative, plausible stories of how a future for LAC could unfold.

For most world regions, the central challenge is defined as the swift return to a prepandemic normal or embrace of opportunities in a new normal. For LAC, the former will not be enough. For several significant reasons, the region needs to improve upon the conditions that existed in early 2020. The pandemic not only exposed the region’s structural vulnerabilities but became a significant stressor with medium- and long-term impacts. While each country is unique, many overarching challenges are shared across the region.

Before the pandemic began, LAC’s overall economic performance was the worst of any world region, measuring a measly 0.1 percent growth in gross domestic product (GDP) during 2019. Between 2013 and 2019, LAC’s GDP growth averaged an underwhelming 0.8 percent.1Michael Reid, “Latin America’s Second ‘Lost Decade’ Is Not as Bad as the First,” Economist, December 12, 2019, https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2019/12/12/latin-americas-second-lost-decade-is-not-as-bad-as-the-first Although this poor performance came after a lengthy period of more robust growth, with a rising middle class and the lifting of millions out of poverty, the region never has been able to place itself on equitable economic and social footing and achieve a sustained convergence to more developed countries. The region is the world’s most unequal, with a large divide in access to public and private goods, ranging from economic and educational opportunities to healthcare provision and a clean and safe environment. This has been exacerbated by pervasive high levels of labor informality. LAC also has exhibited chronic or structural low private investment (16 percent of GDP) compared with other regions, affecting productivity, innovation, and formal job creation.2Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, “Balance Preliminar de las Economías de América Latina y el Caribe,” December 16, 2020, https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/presentation/files/final_final_balance_preliminar.pdf.

To this list of economic challenges must be added political obstacles that threaten the now decades-long evolution toward more robust democratic governance in many countries. While the pandemic led to temporary improvement in popular support for national leaders in parts of the region, as the crisis has progressed citizens have become increasingly dissatisfied with the status quo. The ensuing government and societal responses vary greatly from country to country, with some authorities using the pandemic as an opportunity to expand their power and control. Alarmingly, COVID-19 has increased political polarization among certain population groups and countries, rather than uniting them under a common cause.3“Perceptions of Democracy in Latin America during COVID-19,” Luminate webpage, December 1, 2020, https://luminategroup.com/perceptions-of-democracy-in-latin-america. This trend compounds an underlying discontent that had found expression in popular protests in 2019. 4Cecilia Barría, “Coronavirus en América Latina | ‘Ya está empesando una segunda ola de estallido social’: entrevista a María Victoria Murillo,” BBC Mundo, September 22, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-54244590.

Added to all these pressures are other preexisting challenges facing LAC, not least of which is the threat of a rapidly changing climate, which motivated 7,000 Honduran migrants to make the perilous journey to the United States after two major hurricanes in 2020. Even absent climate disasters, hundreds of thousands of people migrate each year due to wide economic disparities in the region, creating a substantial drain on the human capital of certain countries and fueling the growth of increasingly sophisticated smuggling networks that themselves present governance challenges to countries along the smuggling pathways. In addition, an unsettled global economic and geopolitical context will have critical repercussions for LAC’s development through 2025, especially in the trade and investment arena. In particular, the fraught bilateral relationship between the United States and China—the world’s two largest economies and trading nations—will have outsized consequences for the region’s economic growth in the years to come.

On the bright side, however, there are some opportunities to reset conditions in the region, several of which represent the flip side of the challenges. For example, although the pandemic created new societal pressures, in some cases it also created space for renewed commitment from civil society and the general public for political and other reforms, notably through online activism. Although digital transformation accelerated during the pandemic, altering entire industries and requiring sometimes wrenching labor-market adjustments, this transformation also represents an opportunity for some firms and workers to build resilience and thrive.5Laura LaBerge et al., “How COVID-19 Has Pushed Companies over the Technology Tipping Point–and Transformed Business Forever,” McKinsey & Company, October 5, 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/how-covid-19-has-pushed-companies-over-the-technology-tipping-point-and-transformed-business-forever. Accelerated digitalization, artificial intelligence-enhanced operations, and other technology-driven economic changes already are sources of new industries and employment.

In addition, while the pandemic caused an initial global trade collapse, it also could deepen regional integration and expand reshoring/nearshoring gains as companies bring activities back to or near consumer markets, reinforcing the prepandemic reconfiguration of global value chains.6Piergiuseppe Fortunato, “How COVID-19 Is Changing Global Value Chains,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), September 2, 2020, https://unctad.org/news/how-covid-19-changing-global-value-chains. In the case of the Caribbean countries, developing a regional economy for essential items, such as foodstuffs and medical supplies, could create new economic opportunities and enhance the subregion’s economic resilience.7Country Department Caribbean, LAC Post Covid-19: Challenges and Opportunities, Inter-American Development Bank, 2020, https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/LAC-Post-COVID-19-Challenges-and-Opportunities-for-CCB.pdf. Opportunities in these and other areas can provide much-needed momentum to help jump-start a private-sector-led recovery, in the context of strained public finances. Translating the potential dividend of these opportunities into long-lasting economic growth calls for the following: higher levels of investment and innovation; more efficient, effective, and transparent institutions; and policy reforms to foster a thriving environment for private initiatives and quality citizen-centered public service delivery, with a view to help reactivate the productive sector, promote job creation, and mitigate the socioeconomic reversal caused by the crisis.

The following pages aim to provide a contextual framework for unpacking these issues. Section II presents an analysis of three fundamental drivers of change for the LAC region: public health outcomes, societal agency, and global forces (with the US-China bilateral relationship at its center). Section III offers three fictional yet plausible stories (scenarios) for the LAC region through 2025. Section IV suggests ways in which the reader can use the report as a tool for post-COVID thinking and planning.

This strategic foresight exercise is designed to explore, through the creation of alternative scenarios, ways in which key factors and uncertainties might evolve, interact, and shape LAC’s post-COVID future. It provides food for thought for relevant stakeholders, particularly policy makers, to help enhance forward-thinking and proactive planning. While the report focuses mainly on broad regional issues, it recognizes the importance of distinct subregional and national dynamics. A country-specific deep dive is needed to fully explore the specificities in each case.

This report is based upon a research process initiated at the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and then joined by the Atlantic Council. The IDB conducted an extensive internal exercise that (a) identified core drivers of change that might significantly affect the region’s trajectory during and after the pandemic and (b) enabled the development of three initial draft scenarios for the region out to 2025. The Atlantic Council and the IDB together subsequently delved deeper into the drivers and detailed the scenarios that are offered in Sections II and III of this paper. NormannPartners provided support throughout the whole process. A fuller description of this process is contained in Appendix 1.

II. Key Uncertainties for a Post-COVID Latin America and the Caribbean

SETTING THE STAGE

Since early 2020, COVID-19 has taken a colossal human and socioeconomic toll around the world. As of March 25, 2021, the pandemic has caused 125 million infections and 2.7 million fatalities.8Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE), “COVID-19 Dashboard,” Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University & Medicine, last updated February 16, 2021, https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) most recent analysis estimates that COVID-19 caused a 3.5 percent global economic contraction during 2020 and forced ninety million people into extreme poverty (defined by the IMF as incomes less than $1.90 per day).9International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook Update: Policy Support and Vaccines Expected to Lift Activity,” January 26, 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/01/26/2021-world-economic-outlook-update. Even as economies begin to return to normal, the lingering effects of the virus and lockdowns may discourage economic activities that require in-person proximity. This could have a 10 percent impact on output, creating at least temporarily a “90 percent economy” wherein certain categories of employment remain severely diminished or even eliminated after the end of the pandemic.10James Fransham and Callum Williams,“The 90% Economy that Lockdowns Will Leave Behind,” Economist, April 30, 2020, https://www.economist.com/briefing/2020/04/30/the-90-economy-that-lockdowns-will-leave-behind. For the global economy as a whole, the IMF forecasts a “long, uneven, and uncertain [postpandemic] ascent” by the end of 2025 and a cumulative $28 trillion loss in global output compared to the prepandemic trajectory.11Gita Gopinath, “A Long, Uneven and Uncertain Ascent,” IMFBlog: Insights & Analysis on Economics & Finance, International Monetary Fund, October 13, 2020, https://blogs.imf.org/2020/10/13/a-long-uneven-and-uncertain-ascent/.

Against this global backdrop, the LAC region stands out as among the hardest hit in terms of both COVID-19 cases and economic impact. Although the region represents just 8 percent of the global population, LAC consistently represents nearly 20 percent of the world’s COVID-19 cases and one-third of fatalities.12World Health Organization, “WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard,” accessed February 28, 2021, https://covid19.who.int/table. Additionally, the region has repeatedly recorded some of the worst COVID-19 mortality figures, whether measured in absolute terms, observed case-mortality ratio, or deaths per 100,000 persons.13Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE), “COVID-19 Dashboard.” In economic terms, the region is expected to have suffered an economic contraction of 7 percent, the deepest contraction experienced among emerging markets (for comparison, sub-Saharan Africa’s economy is expected to have suffered an economic contraction of 7 percent, the deepest contraction in 2020 experienced among emerging markets (for comparison, sub-Saharan Africa’s economy is estimated to have contracted 1.9 percent while the Middle East/Central Asia’s economy contracted 2.9 percent).14International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook: Managing Divergent Recoveries,” April, 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/03/23/world-economic-outlook-april-2021.

LAC’s labor markets also have suffered considerably due to the pandemic, especially in comparison to other areas of the world. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated a loss of thirty-five million jobs or a 16.2 percent year-to-year loss in total-working hours, nearly double the global average of 8.8 percent.15International Labour Organization, ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work, 7th ed., January 25, 2021, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_767028.pdf; and Oscar Arboleda et al., “Social Policies in Response to Coronovarius: Labor Markets of Latin America and the Caribbean in the Face of the Impact of COVID-19,” IDB, April 2020, http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0002312. This is attributable in part to the fact that many LAC countries, despite great heterogeneity, derive much employment in the informal economy and sectors that are not geared to working from home, which are among the worst-hit by the coronavirus.

Tightening labor conditions likely will weigh on regional growth in coming years. Even before the pandemic, employment expansion—which accounted for roughly 80 percent of LAC’s growth between 2000 and 2015—was already expected to diminish, potentially making LAC’s GDP growth 40 percent weaker between 2015 and 2030.16Andrés Cadena, Jaana Remes, Nicolás Grosman, and André de Oliveira, Where Will Latin America’s Growth Come From?, McKinsey Global Institute, April 2017, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/employment%20and%20growth/how%20to%20counter%20three%20threats%20to%20growth%20in%20latin%20america/mgi-discussion-paper-where-will-latin-americas-growth-come-from-april-2017.ashx. With COVID-19 dampening job creation, other growth drivers such as productivity gains must rise to the challenge and fill in the gap. Improving educational outcomes, investing in infrastructure and research and development (R&D), strengthening institutions, competition policies, and the business climate will be key to fostering productivity growth.

Moreover, effective mobilization of private-sector investment could lead to additional productivity improvements. On average, total investment as a percentage of GDP continues to remain lower in LAC countries than the global average (16 percent compared to 26 percent) and much less than their Asian peers.17Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, “Balance Preliminar de las Economías.” LAC also has fallen behind other regions in investing in robust innovation ecosystems that are fundamental for value-added transformation.18Juan Carlos Navarro, José Miguel Benavente, and Gustavo Crespi, “The New Imperative of Innovation: Policy Perspectives for Latin America and the Caribbean,” IDB, February 2016, https://publications.iadb.org/en/new-imperative-innovation-policy-perspectives-latin-america-and-caribbean. The authors outline the main constraints that limit the development of a high-growth innovation ecosystem in the region, including a lack of investment in research and development, the need to further develop entrepreneurship, venture capital, and private innovation finance, and the need to improve infrastructure for science and technology. In sum, the region’s current economic structure has left it highly vulnerable to shocks, including those stemming from the COVID-19 crisis. These challenges are further compounded by the region’s high vulnerability to climate change; the region is the second most disaster-prone region in the world.19Over the 2000-2019 period, the LAC region was hit by 1,205 disasters affecting more than 150 million people. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, “Natural Disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean 2000-2019,” March 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/20191203-ocha-desastres_naturales.pdf.

As is true nearly everywhere, the pandemic has increased debt levels significantly within the region, albeit with widely varying levels and types of indebtedness. As of January 2021, 63 percent of the IMF’s COVID-19 response lending was allocated to LAC countries.20Andrea Shalal, “IMF Chief Says 62% of COVID-19 Lending Went to Latin America,” Reuters, updated December 15, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-imf-latam/imf-chief-says-62-of-covid-19-lending-went-to-latin-america-idUSKBN28P2BN. The IMF projected that the average debt-to-GDP ratio within the region would rise from 70 percent in 2019 to 78.7 percent in 2020 and only decrease slightly to 75.4 by 2021.21IMF, “Fiscal Monitor Update, January 2021,” January 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2021/01/20/fiscal-monitor-update-january-2021. Private-sector debt has increased, potentially amplifying financial risks associated with insolvency, rollovers, and currency mismatch.22Andrew Powell, “On the Macroeconomics of Covid-19 and the Risks That Will Be Left in its Wake,” Ideas Matter blog, IDB, January 6, 2021, https://blogs.iadb.org/ideas-matter/en/on-the-macroeconomics-of-covid-19-and-the-risks-that-will-be-left-in-its-wake/#_ftn5; Center for Global Development and IDB, Sound Banks for Healthy Economies: Challenges for Policymakers in Latin America and the Caribbean in Times of Coronavirus, a CGD-IDB Working Group Report, Andrew Powell and Liliana Rojas-Suarez, chairs, 2020, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/CGD-IDB-Working-Group-Report-English-October.pdf. As balance sheets deteriorate globally and in Latin America, the corporate and banking sectors could face another stress test with a lurking credit crunch, which also disproportionately and regressively affects household and small-firm borrowers.23Carmen M. Reinhart, “The Quite Financial Crisis,” Project Syndicate, January 7, 2020, https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/covid19-balance-sheets-quiet-financial-crisis-by-carmen-reinhart-2021-01. The bulk of the region’s debt accumulation is through private markets rather than public-sector creditors such as international development banks and sovereign governments. As a result, debt restructuring might be complex”.24Andrew Powell and Oscar Valencia, “Avoiding a New Lost Decade for Latin America and the Caribbean,” IDB, October 15, 2020, https://blogs.iadb.org/ideas-matter/en/another-lost-decade-for-latin-america-and-the-caribbean/.

Economic and health concerns fuel into and are compounded by other sources of prepandemic societal discontent, such as human insecurity and crime, corruption, multidimensional socioeconomic inequality, insufficient provision of public goods and services, and environmental degradation. Even before the pandemic struck, heightened sociopolitical volatility caused protests across LAC. In several cases, political polarization and the rise of populism were already well underway, with divergent implications for elections, institutions, and the rule of law. As the region looks beyond the pandemic, it will need to keep in mind that forty-four million of its inhabitants could fall below the poverty line and fifty-two million could be pushed out of the middle class. These outcomes would reverse much of the hard-fought socioeconomic progress made in LAC from 2000 to 2018, and could have long-term implications for the political stability of the region.25Ivonne Acevedo et al., “Implicaciones sociales del Covid-19: Estimaciones y alternativas para América Latina y El Caribe,” IDB, October 2020https://publications.iadb.org/es/implicaciones-sociales-del-covid-19-estimaciones-y-alternativas-para-america-latina-y-el-caribe. Extreme poverty is defined to encompass those living on daily per capita income below US$3. Moderate poverty is defined to encompass those living on daily per capita income of between US$3.01 and US$5. Consolidated middle class is defined to encompass those living on daily per capita income of between US$12.40 and US$62. According to a new study from the IMF, the risk of riots and antigovernment protests increases over time, following an epidemic, as does the risk of a major government crisis.26Philip Barrett, Sophia Chen, and Nan Li, “COVID’s Long Shadow: Social Repercussions of Pandemics,” IMFBlog: Insights & Analysis on Economics & Finance, International Monetary Fund, February 3, 2021, https://blogs.imf.org/2021/02/03/covids-long-shadow-social-repercussions-of-pandemics/. If history is any guide, unrest could reemerge as the pandemic subsides, especially in a region where the crisis is expected to worsen existing inequality.

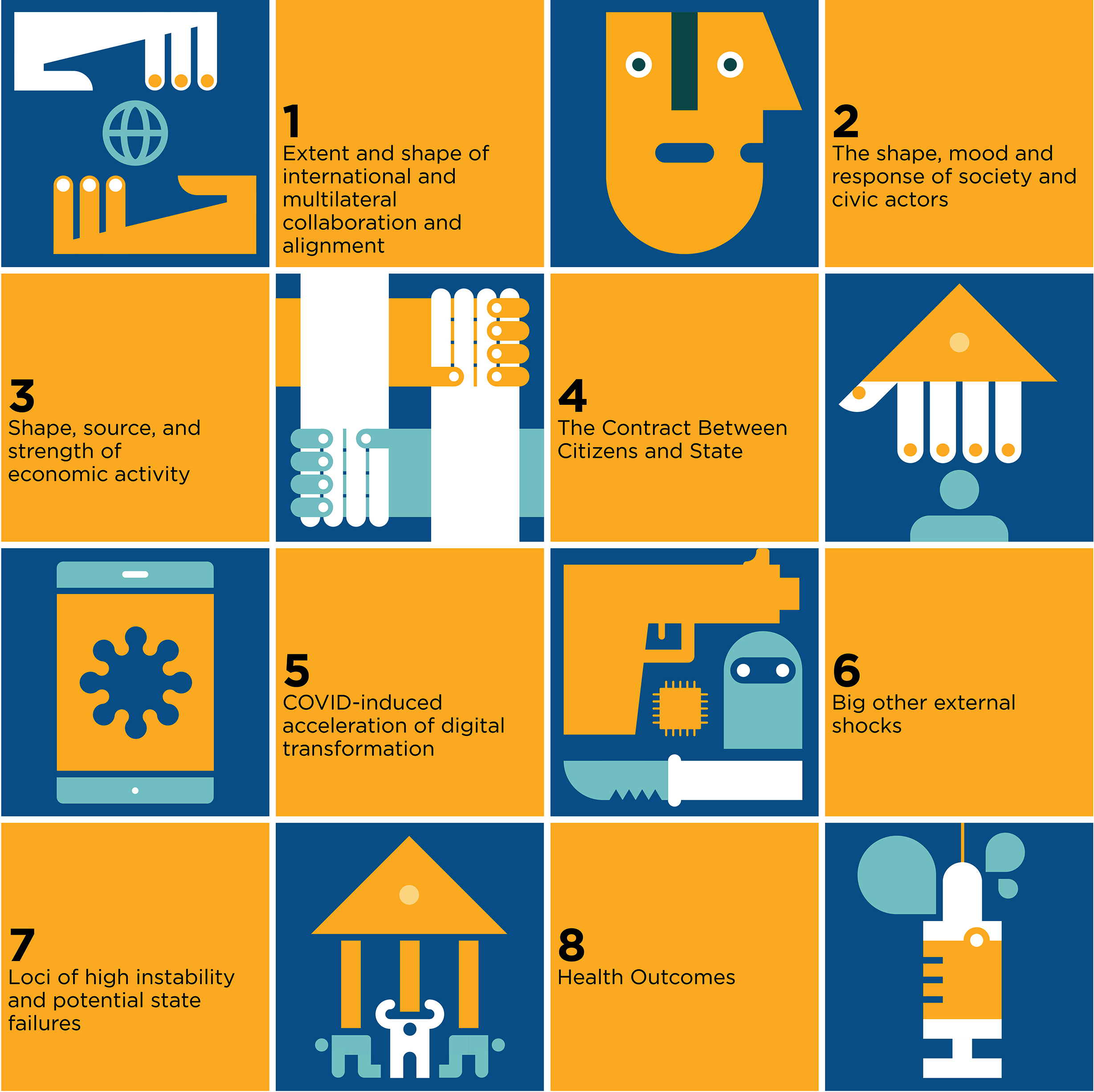

FIGURE 1

DOMINANT CONFIGURING FACTORS

Following a robust research and consultation process during the summer and fall of 2020 (which is described in Appendix I), the IDB identified a set of three key driving factors—labeled dominant configuring factors (DCFs)—from a large set of global forces and uncertainties, as being particularly relevant for shaping regional outcomes over the next several years: (a) public health outcomes; (b) societal agency; and (c) LAC in the global landscape (see Figure 1).27Dominant configuring factors (© NormannPartners) are clusters of factors of uncertainty, captured in one overarching phrase or factor with multiple different and plausible outcomes or unfoldings (i.e., at least two). DCFs help to synthesize and organize a large collection of drivers of change into smaller sets. If this set is five or less, they can be used for a deductive step in inductive scenario-building processes. Key developments and trends within and across these three DCFs will be significant in determining LAC’s post-COVID future and informing and influencing regional policy and strategy discussions.

A. HEALTH OUTCOMES

In 2020, unprecedented global R&D efforts and collaboration produced a race for COVID-19 vaccines, with multiple forerunners showing satisfactory efficacy and being rolled out by year-end. As of March 26, 2021, thirteen vaccines had been approved by national health authorities around the world for limited or full use, including six currently being administered in LAC.28The six vaccines currently approved are the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, the Sputnik V vaccine, the Convidecia vaccine manufactured by CanSino Biologics, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, the BBIBP-CorV vaccine developed by the Beijing Institute, and the CoronaVac vaccine manufactured by Sinovac Biotech. Moderna has yet to be approved in LAC per a New York Times tracker. While the vaccines’ efficacies now appear to be high, other uncertainties remain, e.g., side effects, duration of immunity, and protection against current and future viral mutations. The unfolding of these uncertainties—over time and through additional trials—will directly alter health outcomes in the coming years. Whether the vaccines and therapeutic drugs can succeed in widespread containment of the disease will have an outsized impact on all post-COVID scenarios for the region and the world.

Regardless of vaccine properties and efficacies, a significant hurdle involves rapid, efficient, and equitable immunization at scale within the region, especially among rural, poor, and other underserved communities. This could lead to potentially divergent outcomes both within and across countries. As seen in the initial stages of vaccine rollouts, even advanced economies could experience hiccups in production ramp-up and delivery.29Reuters staff, “Cold Chain Doubts Delay COVID-19 Vaccinations in Some German Cities,” Reuters, updated December 27, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-europe-vaccines-germa/cold-chain-doubts-delay-covid-19-vaccinations-in-some-german-cities-idUSL1N2J7083; and Costas Paris, “Supply-Chain Obstacles Led to Last Month’s Cut to Pfizer’s Covid-19 Vaccine-Rollout Target,” Wall Street Journal, updated December 3, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/pfizer-slashed-its-covid-19-vaccine-rollout-target-after-facing-supply-chain-obstacles-11607027787. Vaccine hesitancy (referring to people delaying or refusing vaccination despite its availability) poses an additional challenge, accentuated by the lack of informational transparency and the politicization of vaccines (e.g., Chinese/Russian versus Western vaccines) in numerous LAC countries. A holistic plan for vaccine acquisition, distribution, and readiness will help to mitigate logistical and storage bottlenecks—for example, related to cold storage chains—as well as other obstacles such as vaccine hesitancy and medical personnel shortage.30Pepe Zhang, “Moving Beyond COVID-19: Vaccines and Other Policy Considerations in Latin America,” Atlantic Council, December 4, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/moving-beyond-covid-19-vaccines-and-other-policy-considerations-in-latin-america/. In the issue brief, Zhang offers an eight-point plan for vaccine acquisition and distribution.

In the absence of adequate planning and deployment, delayed and uneven access to vaccines will hamper the pace and resilience of LAC’s economic recovery. This will weigh especially on demand-intensive sectors such as tourism, which is an important source of individual, corporate, and government revenues—particularly in Caribbean countries—but which has collapsed during the pandemic. Corruption may lead to additional inequity and inefficiency in vaccine distribution. On the social front, the pandemic has once again laid bare the region’s challenges and vulnerabilities on inequality. COVID-19 struck an already highly stratified region that long has suffered from some of the world’s largest gaps in rich-versus-poor access to education, healthcare, and other public goods.31Luis Alberto Moreno, “Latin America’s Lost Decades,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/south-america/2020-12-08/latin-americas-lost-decades.

On the one hand, the pandemic represents a chance to reset how the region treats its disparities. On the other, there is a real risk that vaccine access will exacerbate LAC’s multidimensional inequalities—economic, gender-based, and rural versus urban—and that outcome could fuel migration. Numerous reports have found that the pandemic has had an unequal impact on women, informal workers, and indigenous and rural communities.

Further, COVID-19’s unequal impacts speak to structural deficits in the region’s healthcare systems. Even beyond the inequality of access, the region’s long-standing underinvestment in healthcare has left it ill prepared for this pandemic. LAC countries score poorly compared with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average, spending 6.6 percent of GDP on healthcare versus the OECD average of 8.8 percent.32OECD/World Bank, “Health Expenditure per Capita and in Relation to GDP,” in Health at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2020, OECD Publishing, 2020, accessed November 19, 2020, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/6089164f-en/1/3/6/1/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/6089164f-en&_csp_=1ac29f0301b3ca43ec2dd66bb33522eb&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=book. They typically have less than half the number of hospital beds per capita than the OECD average (2.1 versus 4.7 beds per one thousand people), fewer than half the number of doctors and one-third the number of nurses per capita (two versus 3.5 doctors per thousand people; three versus nine nurses per one thousand people), and a higher share of out-of-pocket health expenditures (a 34 percent spending share on average in LAC versus the OECD average of 21 percent).33OECD/World Bank, Health at a Glance, 9-12, accessed January 16, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1787/6089164f-en.

After the pandemic, the region—like the rest of the world—could see an increase in diagnoses of non-COVID-19 conditions, the result of a backlog of missed or delayed appointments during the pandemic. This eventuality should pose yet another healthcare stress test for the region, which is particularly vulnerable to cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, and other diseases given the high incidence of overweight and obese people plus the region’s other risk factors for noncommunicable diseases.34OECD/World Bank, Health at a Glance, 15-17; Pan American Health Organization and WHO, “Health in the Americas: Mortality in the Americas,” PAHO website accessed January 16, 2020, https://www.paho.org/salud-en-las-americas-2017/?tag=diabetes. Likewise, mental health could become another source of “non-COVID” health concerns, as the region fully fathoms the psychological impact of the pandemic, its economic spillovers, and the recurring and extended lockdowns (in attempts to slow the spread of the virus, LAC countries implemented some of the world’s longest and strictest lockdowns in 2020, drastically altering the daily lives of millions). Chronic underinvestment in mental healthcare services leaves the region ill prepared to address such a widespread challenge, which also poses a threat to the region’s productivity as citizens struggle to cope with the pandemic’s multiple emotional and physiological stresses.

BOX 1

Inequalities in LAC

The multiple forms of legacy inequalities in the region (affecting residents by geography, socioeconomic status, gender, race and ethnicity, and other factors) have worsened during COVID-19.35Luis Alberto Moreno, “Latin America’s Lost Decades.” This is particularly true for women, persons with disabilities, migrants, indigenous people, those of African descent, LGBTQ+ individuals, and other marginalized groups as they already had lower rates of labor force participation and formality than the rest of the population. Women are particularly affected, as they predominate the most deeply affected sectors including the retail sector, which employs an estimated 21.9 percent of LAC working women, and the hotel and restaurant industries.36Alejandra Mora Mora, COVID-19 en la vida de las mujeres: Razones para reconocer los impactos diferenciados, a Inter-American Commis- sion of Women and the Organization of America States, May 1, 2020, https://www.oas.org/es/cim/docs/ArgumentarioCOVID19-ES.pdf. In addition, new forms of inequality, including digital, climate, and migration, have emerged. For instance, the five hundred thousand or more economic and climate migrants from Central America and more than five million Venezuelans who have left their country in the largest regional migration in recent history will face even greater hardship during and after COVID-19.37Peter J. Meyer and Maureen Taft-Morales, “Central American Migrations: Root Causes and US Policy,” Congressional Research Service, updat- ed June 13, 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF11151.pdf; and International Organization for Migration, “Profile of Venezuelan Refugees and Migrants in Latin America & the Caribbean Reveals Country-to-Country Variations in their Characteristics and Experiences,” press release, August 27, 2020, https://www.iom.int/news/profile-venezuelan-refugees-and-migrants-latin-america-caribbean-reveals-country-country. There also is the prospect for increasing migratory flows as recovery and vaccine availability vary across the region.

Digital technologies, which the pandemic has shown are critical tools for participation in the economy, in theory should enable convergence of economic opportunity and contribute to upward social mobility. The reality, however, is quite different in LAC. The pandemic is expected to increase the educational and professional gaps between rural and urban communities as containment measures force citizens to work and study from home, revealing a geographic digital divide. According to an IDB report, less than 37 percent of rural inhabitants have good connectivity while an average of 71 percent of urban dwellers do.38“Rural Connectivity in Latin America and the Caribbean–A Bridge to Sustainable Development During a Pandemic,” a joint project of IDB, Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture, and Microsoft, October 29, 2020, https://www.iica. int/en/press/events/rural-connectivity-latin-america-and-caribbean-bridge-sustainable-development-during. During the pandemic, limited internet penetration has forced de facto school closures in underserved communities.39Ryan Dube, “Bolivia Decision to Cancel School Because of Covid-19 Upsets Parents,” Wall Street Journal, August 4, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/bolivia-decision-to-cancel-school-because-of-covid-19-upsets-parents-11596577822. Relatedly, LAC’s sizable informal sector—accounting for more than 60 percent of active workers in the region, including many in close-contact professions that cannot be performed in a digital environment—has been among the worst hit.40Antonio David, Samuel Pienknagura, and Jorge Roldos, “Latin America’s Informal Economy Dilemma,” Diálo- go a Fondo, IMF blog, March 12, 2020, https://blog-dialogoafondo.imf.org/?page_id=12943.

The digital divide, with its various underlying contributing factors, also illustrates the complex challenge of mitigating any systemic inequality in LAC. Expansion of digital infrastructure to cover the poorest households and institutions, such as schools in low-income neighborhoods, will be a difficult task by itself. Broader and sustained improvements in other complementary areas also will be needed, from formalizing labor markets to improving health coverage and social protection. Doing so within budgetary constraints (worsened by COVID-19) will require meaningful fiscal reforms to boost revenue collection and smart spending.

B. SOCIETAL AGENCY

COVID-19 has magnified preexisting fault lines in societies around the world. The unequal impacts of the evolution of the outbreak on employment and livelihoods, the repeated quarantine and ongoing behavioral mandates (social distancing, etc.), the social media-driven misinformation about the pandemic and official responses to it, all combined with existing frustrations about good governance, have added new sources of turbulence to an already uncertain societal dynamic in many countries. Many of these potential causes of social disillusionment and division are well documented in in the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2021.41Notes to Pages 11 to 14 World Economic Forum, The Global Risks Report 2021, January 19, 2021, https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2021.

Although some democratic governments, for example in the Asia-Pacific region (e.g., South Korea, New Zealand), have performed well at containing the virus and therefore have kept discontent muted, others have suffered to varying degrees from high levels of public dissatisfaction at the lack of progress. In LAC, some governments experienced initial increases in popularity at the onset of the pandemic. Now, as the crisis drags on and citizens struggle to manage its economic and health impacts, many leaders’ approval ratings are falling.42Directorio Legislativo, Imagen del poder, Poder de la imagen, November 2020, https://alertas.directoriolegislativo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Imagen-del-Poder-Noviembre-2020.pdf; Felipe Estefan, Gabriela Hadid, and Rafael Georges, “Measuring Perceptions of Democracy in Latin America during COVID-19, Luminate, December 1, 2020, https://luminategroup.com/posts/blog/measuring-perceptions-of-democracy-in-latin-america-during-covid-19.

Far worse is the apparent backsliding of democratic governance in many countries during the COVID-19 crisis. An October 2020 Freedom House report found that democracy and human rights have retreated in eighty countries since the onset of the pandemic, including twelve in LAC. Particularly in weaker democracies and under already repressive regimes, the report uncovered abuses that were catalyzed by the pandemic including: the overstepping of officials’ legal authority (e.g., to grant themselves special emergency powers to interfere in judicial systems); greatly expanded citizen surveillance capabilities; discriminatory measures targeted at marginalized groups (such as refugees and minorities); severe news media restrictions; denial of access to official public health data; and interference in elections.43Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz, Democracy Under Lockdown, Freedom House, October 2020, 2-9, https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/democracy-under-lockdown.

Uncertainties about state and society are pronounced in LAC. Prior to 2020, anemic growth rates were exacerbated by social unrest in several countries. While governments increased public spending by an average of 6 percent of GDP over the last two decades, these increases only led to limited improvements in the quantity and quality of services that the region’s emergent-but-fragile middle class expected.44Alejandro Izquierdo, Carola Pessino, and Guillermo Vuletin, eds., Better Spending For Better Lives: How Latin America and the Caribbean Can Do More with Less, IDB, 2018, https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Better-Spending-for-Better-Lives-How-Latin-America-and-the-Caribbean-Can-Do-More-with-Less.pdf. As a result, that middle class took to the streets in 2019-2020 to demand higher-quality service delivery and government responsiveness. As governments struggled to mitigate the pandemic’s impact, additional underlying structural weaknesses, including economic inequality (see Box 1) and unsafe or inadequate living conditions, became increasingly apparent. Many of these weaknesses have hamstrung the region’s pandemic response and could also derail its post-COVID recovery, potentially setting off a downward spiral in socioeconomic development. While protests had subsided early in the pandemic, they returned in the third quarter of 2020 and are likely to continue in the coming years.45Deutsche Welle, “Chile registra segunda jornada de protestas post-confinamiento,” report by the German state-owned broadcaster, September 5, 2020, https://www.dw.com/es/chile-registra-segunda-jornada-de-protestas-post-confinamiento/a-54823301. This time around, governments will have decreased fiscal space to respond to citizens’ demands as they direct funds toward servicing public debt.

Limited resources will affect governments’ ability to meet their citizens’ needs and fight poverty. Absent proactive policy making, the region could face greater social instability than that experienced in 2019 or 2020. Alternatively, however, public frustration could become a constructive force if exercised and channeled effectively, as renewed citizen engagement delivers fresh momentum for meaningful socioeconomic improvements. A key driver of uncertainty for the region’s postpandemic future will be the participation and actions of its citizens in forging answers to the list of challenges in the preceding paragraphs. The degree and direction of citizen activism (i.e., societal agency) will do much to determine whether LAC could transform the pandemic into an inflection point toward positive structural changes at all levels of government (local to national).

There are encouraging signs. In parts of LAC, competent local authorities have adroitly secured and deployed the emergency resources and responsibilities that came about during the pandemic, propelling new thinking and possibly new leaders to national preeminence. Digital engagement, while not without its flaws (e.g., the spread of misinformation), has given voice to a broader group of previously underrepresented constituents. This includes a generation of increasingly politically active youth, conscious of climate and technological risks and concerned with the “ni-ni” challenges (of youth who are not in school and not in work) widening with the pandemic.46Ni-ni refers to youth who are out of school and out of work in Latin America. They neither study nor work (ni estudia, ni trabaja). An active civil society will have the opportunity to make its voice heard through twenty-four general elections in LAC between 2021 and 2025 (with five in 2021).47Carla Y. Davis-Castro and David A. Blum, “Latin American and the Caribbean: Fact Sheet on Leaders and Elections,” Congressional Research Service, updated August 5, 2020, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/2020-08-05_98-684_95fa9ba1d522feebf67a98e072585e42e16ec742.pdf. Citizen participation alone cannot achieve these ambitious transformations; governments, business and civil-society leaders, and the international community also have a role to play. Creating consensus around a more inclusive growth model and social contract across these groups will be necessary not only for moving the needle on major reforms in LAC nations, but also for restoring citizens’ trust in their government. Failure to do so risks eroding confidence in democracy and institutions in parts of LAC, and could aggravate democratic backsliding, systemic corruption, and political polarization.48Estefan, Hadid, and Georges, “Measuring Perceptions.” The private sector, where a management theory of stakeholder capitalism (as opposed to a strict focus on shareholders) is gaining currency, could be an important ally in this whole-of-society effort.49Doug Sundheim and Kate Starr, “Making Stakeholder Capitalism a Reality,” Harvard Business Review, January 22, 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/01/making-stakeholder-capitalism-a-reality. A growing number of responsible companies are including environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations or United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in their business planning and operations.

C. LAC IN THE GLOBAL LANDSCAPE: THE US-CHINA RELATIONSHIP

The international context is a crucial factor, with multiple types of external influence capable of shaping the region’s current and post-COVID trajectory. An incomplete list of such external factors and megatrends includes: the increasingly severe impacts of a changing climate; the future of global, regional, and bilateral trade and investment regimes (an example here is the Amazon deforestation controversy that is holding up the trade agreement between the European Union (EU) and Mercosur, the South American trade bloc); the evolution of technological change and its locational and sectoral effects (e.g., on the geography of manufacturing, lengthening or shortening of global supply chains, 5G impacts on digital and physical economies); global commodity prices such as oil, gas, and foodstuffs (as many Andean and Southern Cone countries are major commodities exporters, the globally driven prices of many commodities have significant economic impacts on the region); and increasingly severe geopolitical fissures that lurk behind many of these challenges (with major global players including the United States, China, Russia, India, and the EU).50On the EU-Mercosur agreement, see Anthony Boadle, “Brazil Pledge on Amazon Needed to Save EU-Mercosur Trade Deal–EU Diplomat,” Reuters, December 7, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/eu-mercosur-brazil/brazil-pledge-on-amazon-needed-to-save-eu-mercosur-trade-deal-eu-diplomat-idUSKBN28H1SP. For additional background reading, see a list of megatrends in a United Nations document: Report of the UN Economist Network for the UN 75th Anniversary Shaping the Trends of Our Time, September 2020, https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2020/09/20-124-UNEN-75Report-2-1.pdf

Each of the above external drivers may have important ramifications for the region. Yet the primary extraregional driver and chief uncertainty for LAC’s postpandemic future is its relationship with the world’s two largest economies and trading nations: the United States and China. LAC’s relationship with both, in turn, will be influenced by the evolution of the bilateral US-China relationship in the coming years. Developments within the United States and China also will play a role, for example through strategic decisions made by political leadership surrounding the bilateral relationship and the relationship with LAC, as well as the pace and extent of economic recovery in both countries, which will drive economic performance elsewhere in the world. Indeed, a 2020 World Bank report identified growth rates in China and the Group of Seven economies (including the United States) as two of the top external shocks for LAC.51World Bank, Semiannual Report of the Latin American and Caribbean Region: The Economy in the Time of COVID-19, April 2020, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33555/9781464815706.pdf?sequence=10&isAllowed=y.

Relations between the United States and China had been stable for decades, until the past four years, which brought about a sea change characterized by heightened tensions and multisector strategic rivalry.52On technology as a geostrategic element within the bilateral US-China relationship, see, e.g., Benjamin Wilhelm, “Overshadowed by a Pandemic, the U.S.-China Tech War Is Heating Up,” World Politics Review, June 10, 2020, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/trend-lines/28830/overshadowed-by-a-pandemic-the-u-s-china-tech-war-is-heating-up. Whether principled pragmatism or broad-brush antagonism will dominate the bilateral relationship in the years ahead could lead to divergent outcomes, from further disintegration to a state of manageable coexistence.53Kurt Campbell and Jake Sullivan, “Competition Without CatastropheHow America Can Both Challenge and Coexist with China,” Foreign Affairs 95 no. 5, (September/October 2019), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/competition-with-china-without-catastrophe The uncertain contours of the US-China relations will have global, multilateral, and regional ramifications, ranging from trade and investment patterns with LAC to the shape of technological innovation and implementation. The current state of the relationship is best demonstrated by the number of tech-related disagreements. The dispute over the rollout of 5G capabilities around the world is an apt example, with the United States applying significant pressure on its allies to limit or prevent the use of Chinese 5G technology, principally from Huawei.54For a summary of European responses to the US-China row over 5G, see Alan Beattie, “Brussels’ Subtle Role Reining in Huawei,” Financial Times, December 3, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/b1b0e883-d694-4dcb-8915-b2d2e8e75245.

On the US side, despite a growing bipartisan agreement regarding China as a top foreign policy priority, much disagreement exists over what exactly US policy toward China should be (within a spectrum of options from engagement to strategic competition to confrontation). On the one hand, “fundamental differences” with China likely will continue, including an unsettled trade relationship and a global race for technological dominance.55On the US government’s rhetorical shift toward China, see Anthony H. Cordesman, “From competition to confrontation with China: The major shift in U.S. policy,” CSIS, August 3, 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/competition-confrontation-china-major-shift-us-policy; On the evolving consensus, see, e.g., Dan Drezner, “Meet the new bipartisan consensus on China, just as wrong as the old bipartisan consensus on China,” The Washington Post, April 28, 2020, The Biden administration also is likely to bring other pressure points to bear on China that the Trump administration did not fully exploit, for example human rights and democracy protection in Hong Kong, or a multilateral approach working with European and Asian allies. On the other hand, there remains an opportunity to ratchet down the temperature and moderate bilateral hostility, especially as the Biden administration seeks nuanced and constructive coordination with Chinese counterparts on key global issues such as climate change. Much work remains to be done here. The Biden team also will also likely return to a more predictable and conventional form of diplomacy, including rhetorically, which should help enhance bilateral dialogues.

On the Chinese side, relative success in pandemic management enabled China to become the only major economy to grow rather than contract in 2020, accelerating its ascent to the world’s largest economy.56BBC, “Chinese Economy to Overtake US ‘by 2028’ Due to Covid,” December 26, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-55454146. However, China’s capacity to become a more constructive global actor within the multilateral system and via bilateral relationships—with the United States, LAC, and others—should be tested more, not less, in the coming years.57BBC, “Chinese Economy to Overtake US ‘by 2028’ Dueu to Covid” China will be expected to hold itself to higher standards and shoulder greater responsibilities in international governance. This, combined with the unfolding of China’s “dual circulation” strategy (referring to China’s recent emphasis on boosting its domestic market in addition to its traditional export orientation), will shape the intensity and priorities of the country’s global engagement during and after COVID-19.58Decoding China’s ‘Dual Circulation’ Strategy,” Project Syndicate, September 29, 2020, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-dual-circulation-economic-model-by-yu-yongding-2020-09

The United States boasts a strong historic and multidimensional relationship with the LAC region spanning across economic, security, cultural, and interpersonal domains. For its part, China has successfully expanded its commercial footprint across LAC, consolidating itself as its second-largest trade partner (only after the United States) as well as a major source of official lending and foreign direct investment (FDI) especially for infrastructure projects.

In recent years, LAC has become subject to the competitive dynamics between the United States and China. However, despite great regional heterogeneity, most countries have publicly opted for a neutral position, demonstrating a willingness to work with both parties in respective areas of interest. In the years ahead, a confluence of exogenous and endogenous factors will determine the impact of US-China relations on the region: (a) to what extent China and the United States will actively engage LAC, as opposed to focusing on domestic issues or other regions; (b) US policy toward Latin America and the Caribbean and US ability to provide feasible alternatives to Chinese investment, technology, goods, and services; (c) whether the United States and China can effectively collaborate on global issues relevant to LAC, e.g., climate change and COVID-19 vaccine rollout; (d) how LAC navigates the regional spillovers of US-China relations, be it positive, such as nearshoring and reshoring opportunities for LAC manufacturers, or negative, e.g., possible unwinding of US-China trade war and its resulting trade-diversion gains for LAC agricultural exporters.

The United States boasts a strong historic and multidimensional relationship with the LAC region spanning across economic, security, cultural, and interpersonal domains.

The interplay among these uncertainties could lead to divergent outcomes for LAC, with commercial and geopolitical repercussions and for LAC’s standing on the world stage. While many in the region reject a false dichotomy between the United States and China, the continuation or moderation of external pressure on side-choosing will have implications for governments in the region and their foreign policy priorities. This, in turn, could create secondary effects on LAC regionalism, for example; intraregional integration and collaboration become increasingly desirable and necessary in an uncertain or even difficult international environment.

III. The Scenarios

The three DCFs described above (health, societal agency, and LAC in the global landscape) will be central in shaping LAC’s post-COVID future. Numerous plausible scenarios result from the interplay across the DCFs, three of which are outlined in this section: (a) COVID’s lasting toll; (b) regionalisms on the rise; and (c) the great divide. Each of the three scenarios was built to provide readers with a useful and contrasting vantage point from which to “look back” at today to challenge predominant perceptions and assumptions, and to reflect on the many pathways and opportunities available.

The reader should not engage these fictional scenarios as forecasts, “most likely” futures, or the “best” or “worst” futures, but rather as alternative, plausible stories of how a future for LAC could unfold. While the set of scenarios does not represent the full array of possibilities facing the region out to 2025, the narratives and their underlying analytical process serve to inform and to help policy makers prepare for the future, while navigating old and new uncertainties that will define the post-COVID region.

Scenario A: COVID’s Lasting Toll

It’s 2025 and after a period of turmoil caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the LAC region and the world are finally on a path to economic recovery and growth. Limited COVID-19 testing capability meant that the full human cost of the crisis has remained unknown. As the region became an epicenter of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, many countries struggled with rising COVID-19 cases and deaths, aggravated by the impact of variants on already stressed health systems. By 2023 and 2024, measures such as the widespread use of masks, prolonged lockdowns, and finally the mass rollout of vaccines to nearly all publics through public, private, and multilateral channels, the COVID-19 outbreak was substantially contained, albeit at great economic and social costs.

Local governments, unable to respond efficiently to the pandemic due to limited resources and a lack of support, believed they had no choice but to strike deals with organized criminal groups to both mitigate the impact of the pandemic and to ensure peace and security.

The pandemic took a heavy long-term toll on the region. Crime and violence initially soared due to the prolonged lockdowns with resulting social and economic impacts, increasing unemployment and learning disruptions, food and housing insecurity, unequal coverage and access to healthcare, and social isolation, among other stressors. Although the region as a whole has begun to recuperate, economic recovery remains elusive for some countries. Millions of migrants have mobilized across the region, looking for better economic prospects and access to healthcare.

As a result of increased insecurity, some armed groups have taken control in isolated (rural) areas and in numerous informal settlements (slums) across the region’s cities, at the governments’ expense. At times these groups have filled the vacuum, providing services to areas under their control as a pacification strategy, thereby eroding support for local and federal governments while enhancing their own power. Although citizens have begun to organize and press for change, more governments than not have cracked down on dissent, utilizing an expanding digital tool kit to surveil citizens. Democratic governance has been eroding in some countries.

ECONOMIC RECOVERY FOLLOWS DOWNTURN

By 2025, the region was experiencing improving macroeconomic conditions, though with great heterogeneity across and within countries. This recovery followed years of downturn that left several of the region’s economies in a substantial hole. Fortunately, debt and inflation finally came under control or were trending downward. Many LAC countries, especially those geographically proximate to the United States, aimed to take advantage of an ongoing US “relocation strategy” to bring production closer to home. Some countries have been more successful in reeling in reshoring and nearshoring investments thanks to a relatively robust regulatory environment, attractive business climate, low energy prices, and preexisting industrial competitiveness. This enabled them to benefit from increased shares of global manufacturing, shifting toward more value-added production within the region.

The private sector began growing, specifically in the information technology-based sectors, with new actors emerging as a result of the digital acceleration, an increase in 5G infrastructure deployment and automation, and a postpandemic start-up boom. However, several factors continued to prevent the fair distribution of gains from economic recovery. Corruption and cronyism remained prevalent. Although local and corporate elites successfully partnered with foreign investors to expand market share into growing business sectors, many small and medium enterprises (SMEs)—severely impacted by the economic downturn of the pandemic—were unable to recover, leaving millions unemployed. The digital divide became more apparent, as a lack of connectivity, particularly in rural areas, caused millions to fall further behind during the extended lockdowns. Disruptive innovators in the gig economy space have created new job opportunities for millions in the region, but also posed new regulatory and economic challenges related to pension, insurance, and other employment benefits.

The tourism sector in several countries, notably across the Caribbean, recovered. In these countries, tourist flows from North America and Europe returned to prepandemic levels by 2024. Additionally, some countries are benefiting from increasing Chinese tourism. However, in parts of the region where crime and violence has increased, tourism has struggled to bounce back. Relatedly, the uneven pace of rebound in international business travel across the region also has affected FDI flows. “Coronavirus-free economies” experienced a rapid replenishment of the FDI pipeline after it had dried out in 2020-2021, whereas others grappled with reduced investor confidence and suppressed asset valuations.

Although some governments implemented recovery packages that included climate-focused elements, many others, particularly in South America, focused on strengthening commodity-based sectors for short-term growth objectives. The private sector has emerged to lead the climate fight in most countries, but investment in sustainability—for example, in Amazon forest protection—has lagged, putting an enormous strain on already degraded natural assets.

DEMOCRATIC EROSION

In several major cities hit hard by the virus, gangs took advantage of further decreased state presence to consolidate their hold on favelas and other informal settlements, utilizing a combination of largesse (social provision in the absence of the state’s) and intimidation. Transnational crime also grew. Local governments, unable to respond efficiently to the pandemic due to limited resources and a lack of support, believed they had no choice but to strike deals with such groups to both mitigate the impact of the pandemic and to ensure peace and security (gangs were willing to restrict violence in exchange for tacit control over their areas).

After the virus was contained, local governments that had built ties with these gangs found that they were unable to regain control. To make matters worse, these tacit agreements began to come to light. So too did various corruption scandals enabled by the agreements, for example, ties to a vaccine black market and even profiting from administering fake vaccines in the affected communities. These revelations occurred while other corruption scandals continued to be investigated, particularly national governments’ mismanagement of funds during the crisis and the early vaccine rollout.

For a while, it was hoped that the pandemic storm and corruption scandals would inspire and generate widespread democratic reform movements. Indeed, in 2021 large citizen mobilizations—including instances of unrest—called for justice, transparency, and accountability. Over time, however, citizens became less engaged. Demonstrations ebbed, especially as governments began deploying more advanced digital tools to monitor and surveil their citizens. Authoritarian governments restricted freedom of speech to control the dissemination of what they labeled as “fake news.” This was achieved virtually through restrictions on social media and physically through the increased use of biometrics. The latter exploited the enhanced availability of personal data through “immunity passports” and contract-tracing apps that embedded health and movement information.

US VERSUS CHINA IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN

Overall, US-China relations have become less confrontational and unpredictable than during 2017-2021, though tensions and competition have persisted. Effective vaccines were developed in the United States, China, Europe, India, Russia, and elsewhere, but many faced significant production challenges, leading to long delays in shipments across the globe in 2021. Ultimately, US, Chinese, and Russian manufacturers accounted for the lion’s share of vaccines used in LAC. In most countries, multiple vaccines—with varied efficacy rates, availability and affordability—were approved and deployed simultaneously.

While the United States and China provided comparable amounts of aid throughout the crisis, memory of the America First rhetoric led to the widespread perception that China had been a better ally. This memory lingered despite the 2021 change in US administration, which led it to once again advocate for multilateral engagement, global standard-setting, and increasing investment and aid to the region (especially to Central America to mitigate the root causes of migration). The winner of the 2024 US presidential election also vowed to continue strong engagement in the hemisphere. China, for its part during and after the pandemic, provided flexible financing options to LAC, such as commodity-backed loans, infrastructure investment, and bilateral debt relief. As a result of severe declines in GDP, most Latin American and Caribbean countries are unwilling to prioritize economic relations with either China or the United States and instead welcomed investment from both countries to foster the region’s economic recovery.

Cooperation between China and some LAC countries began to expand from the traditional infrastructure, energy, and agricultural sectors to increased Chinese investments in public health and the digital economy. At times, investment came hand-in-hand in both strategic areas, helping countries build stronger health systems based on digital identification systems and electronic records, though not without sparking concerns over data ethics and privacy. These measures were neither widespread nor robust enough, by themselves, to overcome the region’s chronic deficit in access to healthcare.

By 2025, the region has begun to recover, but there are large disparities among countries and rural and urban communities. Decisions made at the start of the pandemic, such as the tacit devolution of authority to local criminal organizations, have had lasting adverse impacts for democracy and anti-corruption efforts.

Scenario B: Regionalisms on the Rise

It is 2025, and much of the world has just come through a very difficult period in which it had to repair the social and economic fabric underpinning society. The LAC region likewise was still trying to come to grips with the pandemic’s secondary effects. These effects often were negative, with public and private debt levels, for example, failing to significantly decline after the regional debt-to-GDP ratio reached 74 percent at the end of 2020. Other effects were more positive, including the COVID-induced public-private sector collaboration on pandemic and pharmaceutical research, which proved critical.

The most prominent change in LAC, however, has been a noticeable shift in society, with a new equilibrium emerging among the state, private sector, and communities. This shift came with the advent of two parallel types of regionalism in a subnational and international context, respectively. In the former, local authorities across the region took an increasingly prominent role in society. Amid widespread disillusionment with central governments’ COVID-19 vaccination and recovery plans (compounded by preexisting frustrations with central governments’ high corruption levels and inefficiencies), citizens, the private sector, and local leaders began to join forces to craft and implement solutions that proved durable, timely, and effective. At first, these measures were ad hoc and uncoordinated across the LAC region, but over time a coalescence emerged around successful policy and business innovations. For example, some local governments managed to accelerate vaccine distribution through novel methods, partnerships, and public information campaigns. As a result of these and other successes, citizens became more politically engaged, especially as civil society and the private sector discovered that they could have constructive input into the region’s structural and future challenges.

During 2020-2021, GDP and asset prices fell, generating an uneven and often asymmetric recovery. Decreased demand for fossil fuels worldwide impacted the public finances of the region’s oil exporters. Demand for international aid and assistance skyrocketed, but funds were relatively limited, pushing many LAC economies into frugality and regional cooperation. As LAC’s conventional outward-looking approach and dependence on external growth drivers became increasingly unreliable, intraregional trade, investment, and cooperation expanded. This gave rise to another type of regionalism—as defined by increased regional integration among LAC countries in a “neglectful” international environment. In addition, governments, including local governments, took frugality as an opportunity to optimize available resources more wisely and for broader benefits to society. Many of the region’s citizens and businesses, similarly motivated by this heightened prudence, agreed that broad reforms were needed. In this context, a healthy debate began to surface between the prevailing do-more-with-more economic model and do-better-with-less “frugal economy.” As governments sought to cut back on spending, they turned to the private sector for innovative solutions to fill the void, attracting investment and creating new markets. As a result, a new private-public compact emerged, spurred on by citizens’ strong demand for higher social, economic, and even environmental accountability from the public and private sectors.

THE RISE OF REGIONALISM, LOCAL AUTHORITIES, AND THE PRIVATE SECTOR

As in many other countries where the pandemic was managed with relative success, this outcome would not have occurred without the critical leadership provided by city and state governments. LAC mayors, city councils, and local health authorities designed bold policies based on local needs. Many of them took appropriate measures regarding lockdowns and vaccine distribution, generating higher levels of public confidence in local leaders. Just as critically, they opened constructive channels for dialogue with local constituencies, including business and civil-society leaders and the general public. In a context of frugality, governments worked increasingly together with the private sector to support LAC’s recovery and to combat other shocks such as natural disasters and climate change.

An unintended consequence was the strengthening of local authority at the expense of central governments. Often hindered by partisan politics, central governments failed to develop swift and sufficient responses to the pandemic and its knock-on effects, eroding confidence in their capabilities. Local leadership therefore filled governance and institutional vacuums that had been created by central governments’ perceived inaction. Governors and mayors became more popular, consolidating their ability to forge ambitious policies supported by broad coalitions. At first, these interventions were uncoordinated and ad hoc, driven by local government officials’ desire to shake off the pandemic and its immediate effects. As successful interventions became more broadly known, however, deeper partnerships and synergies took hold among governors, mayors, and industry associations. This model was quickly replicated throughout the region.

Much of this local rejuvenation also was assisted by a renewed commitment to stakeholder capitalism and talent migration in the private sector. Some high-skilled expatriate workers returned to the region from abroad, in part because they discovered that they could telecommute from anywhere. They contributed to new start-up companies launching in cities across the region, with some succeeding and scaling rapidly. Local capital markets also began to deepen, providing new sources of funding opportunities in an era of relatively low global liquidity.

CITIZEN ENGAGEMENT AND INEQUALITY

The pandemic caused many social fault-lines to become more visible. Wide disparities in vaccine access between the rich and poor and across countries made this clear. As well, the pandemic’s economic impact weighed unevenly on populations, with various vulnerable groups taking the brunt: young people and women faced greater risks of unemployment; rural areas suffered a slower recovery due to limited physical and digital connectivity; among others.

As a result, LAC saw a new wave of citizen rallies around social issues. Digital technology played a key role in empowering these movements and interactions between governments and civil society. Where available, digital tools allowed local leaders, including mayors and community representatives, to organize more effectively and bring along newly engaged citizens. Local governments had skilfully used social media during the pandemic to enforce lockdowns and promote social distancing.

Social media helped build local channels for community outreach and develop social capital among digitally native youths, who subsequently became more engaged in their communities. Overall, citizen participation became more active and constructive across many aspects of public life.

RISE IN (ANOTHER FORM OF) REGIONALISM